- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Thunderbird Page 9

Thunderbird Read online

Page 9

Pop, pop, pop.

“I’m sorry,” Mary says.

But Lela doesn’t hear her, and she turns to say “What?”

Mary now takes her two fists and presses them hard against her eyes, so hard the tendons in her wrists stand out like the strings of a plucked guitar—

Then a terrible sound from above.

Boom.

Boom.

BOOM.

Like a giant boulder crashing down, louder and louder from the floors above— everything is shaking, the lights are flickering, bzzt, bzzt, the screaming is there but is swallowed by that terrible sound—

And then it’s fire and smoke and debris— an explosion rocks the corner of the building and everything that Lela is and believes is erased, torn asunder by chunks of white brick, by spinning metal shrapnel from the cubicle frames, melted plastic and scalding toner from the copier, all of it a wave of claws and teeth—

TWENTY-TWO

INTO THE STORM

Miriam wrenches her hand away, nearly falls over the chair. The smell of smoke still sticks in her nose. She can feel the heat of fire on her cheeks.

Lela just sits there. Staring. “You’re an addict. You’re tweaking.”

You have no idea.

Miriam swallows hard. “I have to go.”

“Go. Get the hell out of here, junkie.”

Her arms pulled in tight, she is the needle that threads her way back through the cubicles. The woman at the desk says good-bye but her voice is distant, echoing, and Miriam’s guts roil. She hurries back out of the office and into the main lobby. There. Bathroom. Now.

She throws herself into it, knees open a stall, dry-heaves for ten minutes.

Every heave, she tries to steady herself. Tries to put out of mind the feeling of detonation. The booming. The shuddering. The air clapping against her. The rain of stones a half-second later. The boiling air, the consumptive flame.

But closing the door on those thoughts just opens the door for worse ones: Wade Chee screaming over the phone, the taste of a dead man in the desert greasy on her hungry tongue and between her rending beak, her mother in a hospital bed, the rising waters of a storm-churned river, a plague mask, a falling axe, a saw cutting through ankle bone, a knife stuck deep in a truck driver’s eye—

A knocking on the stall door.

A man’s voice: “Hey, uhhh, you okay in there?”

She stands up. Wipes spit from her mouth. Bile from her chin. Miriam opens the stall door, sees a narrow man standing there— he’s slight, almost delicate, but trying to look tough with his sharp-cut lawyer suit and his Stetson cowboy hat. His eyes go wide and he stammers, “You’re in the men’s room.”

The starveling monkey shrieking at the back of her mind, the one that pulls all the levers and smashes all the buttons, tells her what to do and she lurches forward and grabs his hand—

He’s naked and frail and knock-kneed, standing up in a porcelain tub thirty years from now, all parts of him trembling like a shaved, nervous dog, trembling so hard he’s almost blurry, and his wilted dick points down and his little button nipples point up and he’s dripping wet— water clinging to a birdlike frame peppered with gray snarls of body hair, and he’s calling out, “Are you coming to get me out? Darren? Darren! Are you there? Bah.” And then he takes one step out of the tub and there’s a sound like swwwwwrk! and his right leg goes way too far left and he falls hard, the side of his head hitting the faucet, neck snapping like a thundercrack—

— and even here she can feel the faint Parkinson’s tremble in his hand. Parkinson’s, a cruel disease, one that doesn’t often kill outright but is a demonic prankster, setting up traps that will kill you.

But she can’t help him, and the monkey inside still howls. It bares its teeth and shrieks for death, to know death, to be death, and so Miriam shoulders past him, pushes to the bathroom door, and goes to the elevator.

Her finger hovers over the buttons.

It chooses the third floor. Chooser of the slain. Chooser of elevator buttons.

Third floor. Court offices. White walls, tan carpet, bad paintings of desert flowers. She’s led by the chin now, as if the Reaper has the curl of its scythe hooked in her cheek like a fishhook and is dragging her along. This is a ride she doesn’t want, but she’s on it now, and all parts of her feel callously, fiendishly alive— bright and colorful and horrible, a woman electrocuted after sucking on the broken socket in a string of Christmas lights, buzz buzz blinky blinky.

A woman in a mauve pants suit. Passing by. Head down, staring at a cell phone. Here. Now. Miriam thrusts out an elbow. Knocks the phone out of the woman’s hands. Miriam bends down at the same time to “help her pick it up,” just brushes her cheek with the woman’s ear—

Again the woman has her head down, but this time her nose is buried in a thick file full of pages, something about divorce, something about splitting up assets, and then she hears it from somewhere downstairs— the faint popping of gunfire— and she gives a look toward an old judge tottering past, his belly straining against his black robes. He says, “That what I think it is?” And she’s about to say something but those words are cut off from coming from above, boom, boom, boom, and then detonation—this one coming from the back, the ground shaking and breaking apart, brick and pipe and smoke and swallowing her whole—

“Sorry, I am just so clumsy today,” the woman says.

“It’s me,” Miriam says, stammering. “My fault. Sorry.” She stumbles left, nearly tripping on herself. Head forward, the woman gone, forgotten now— there, a door ahead. Glass, frosted. Register of Wills, Clerk of Orphans’ Court— she has no idea what that last part means or why you’d let a bunch of orphans have a court all to themselves, but the law is absurd, so who cares.

Inside, she sees an old Hispanic woman by a whiteboard, black pen squeaking across it, writing down court dates in a big calendar—

Miriam doesn’t even pretend. She flings caution into a woodchipper and grabs the woman’s hand—

The woman hurries down the hall, toward the doorway marked Register of Wills, Clerk of Orphans’ Court. She hears the gunfire, feels the vibration in the floor as the explosions detonate above— dust, buzzing lights, breaking ceiling, an explosion, the door launches off its hinges, glass everywhere in a belch of smoke. A filing cabinet creaks and falls onto her, breaking her little bird bones—

“Hey!” the woman protests.

Miriam mumbles, “Sorry, thought you were someone else.”

She sees a long-cheeked man, tongue sitting on his bottom lip like he’s a frog hoping to catch flies. He’s just hanging out by the coffee maker staring off into nothing. She darts past and pats him on the cheek—

He’s standing in the corner that detonates, primping up a plastic plant like it needs the attention, and the explosion launches forth from that very spot— a monster leaping from its cave, a trapdoor spider of smoke and flame reaching out and dragging him down and tearing him to swift pieces—

The man says nothing. She just mutters an apology.

More. More. More. She needs more.

She tells herself she needs it because that’s how she finds out what’s happening, but this hissing whisper from the back of her mind asks: Is that really true? Do you need it, or are you just enjoying the show, you sick little fucko?

Miriam flits from death to death, from doom to doom, like a crow picking a little from this carcass, a little from that one— a choosy maggot, a fickle coyote. She reaches out and touches a lawyer. A judge. A clerk. A secretary. All death. All of them here when it happens. Erased by the explosion. Miriam can feel what it’s like to be torn apart by it: some vaporized in an instant, others rent more incompletely by stone and glass, others dead by the shockwaves and aftereffects—

Now people are talking. Pointing. Who is this woman running a circuit around their office? Bumping, touching, grabbing. She hears murmurs: Call the police. And she wants to laugh: You idiots have no idea

, I’m not the danger, I’m the one trying to figure out who murders you, all of you—

And then she thinks: the gunshots. She doesn’t know about those.

Back to the elevator, then. She ducks into an elevator as a cop comes out of the other one. A crumple-nosed slob in a rumpled uniform spies her, yells, “Hey!” just as the doors ding and slide closed. She stabs the button to go back down.

Once more, ground floor of the courthouse.

She heads for the exits.

If anyone knows—

It’s the guards.

Her breath slides cold through her teeth as she goes to Hugo, the old white guard, and she thinks: Act normal, don’t act like an animal, like a freak, like some weird tweaker who jills off every time she catches a whiff of morgue stink. And she says, trying to keep the tremors in her voice invisible and contained:

“I just want to thank you for doing such a good job here.” And she thrusts out her hand, and the liver-spotted old white gent reaches out and takes and shakes her hand—

Three men in full camo, face masks, vests, the whole militarized enchilada— they’ve got black rifles tricked out, and they march forward and spread out, firing into the foyer. A pasty white woman with four Starbucks coffees in a carrier sees her hairline torn back by a .223 bullet. A black man in a fringed denim jacket yells, starts to run, catches a bullet right through the throat and out the back of his spine, his head flopping around like it’s just barely stitched on. Hugo reaches down, feels his heart thundering in his chest like the drumbeat hooves of a cattle stampede and he feels for the gun at his hip, but one of the men turns, points the rifle, and one shot— pop!— and that fast-beating heart has its pulse cut quick by a hot lead injection at eleven hundred feet per second. The old man drops, barely holds himself up by the metal detector. One of the shooters now winds through the detector, and as he does, the old man sees the shooter has his arm exposed, and ink crawling up it— the name JANICE in flowery script along the forearm, and on the bulging bicep, across skin bumpy with earthworm veins, another tattoo: a dead tree with lightning striking it, four words painted indelibly underneath, A STORM IS COMING. Beneath that tattoo, an uneven oval scar, like a cigar burn— or a bullet wound. Then the shooter points the rifle right at the old man’s head and the gun goes off and so does the top of the old man’s head—

Miriam cries out and steps back—

The elevator at the other end of the downstairs dings.

A cop yells.

The old security guard up front hasn’t caught on yet, hasn’t heard the yelling, and he offers Miriam a soft smile and says, “Why, thank you, miss.”

And then she’s hurrying the hell out of there.

TWENTY-THREE

ROASTING MARSHMALLOWS

Miriam orbits the courthouse a few times, just to make sure the cop isn’t following her anymore. When she’s sure, she goes back to the van, opens the back, finds a ratty old loveseat back there, and curls up on it.

She sobs like a hurricane. Gulping gale winds and floods from her eyes.

In three weeks, this building will be destroyed. At least partly. And many of the people inside will die. Either by the explosion or at the hands of the gunmen in the lobby. Bullets and bombs. A mass murder. A terrorist act.

And it all starts to wind together. A coil of barbed wire around her wrists, forming a pair of handcuffs, shackling her to this thing raw and bloody. She wants to say, This isn’t my business, this isn’t my problem, it is neither my circus nor my monkeys, but that is no longer true. Mary Stitch— Mary Scissors, Mary Skizz— is in there when it happens. Which means she dies in three weeks. Worse, the men in the lobby? Same tattoo and motto as the rifleman in the desert. The one who tried to kill her and tried to kill that boy’s mother, Gracie. The one tied to the same group that killed Wade Chee in looking for her.

Miriam wants to leave. Her greatest desire right now is to reach up, pull the ripcord, and eject way the fuck out of this burning, guttering plane. Before it crashes. Before it kills them all.

But now? She can’t.

“You know you like it,” comes a voice from the front seat.

She startles, rolling off the couch and into a crouch. Already she reaches for the knife in her back pocket, opening it with a flick—

Wade Chee leans around the front seat, stares into the back.

He looks the same.

Except for his eyes. Those are like crispy campfire marshmallows. Black charflake on the outside. Gooey, goopy white on the inside.

“Fuck off,” Miriam spits.

“Come on,” Not-Wade says. When he speaks, little embers cough from his mouth— tiny fiber optic filament points glowing bright before going dark. “This is your jam, Miriam Black. This is your bread and butter; this is your sweet spot. This is your circus and”— here he spreads his arms out, and she can hear, if not see, the crinkly sound of burned skin breaking, like potato chips under a stepping foot—“these most certainly are your monkeys.”

“I don’t want any of this.”

Wade’s melting, ruined eyes narrow. Forcing tacky white rivulets to run down his cheek, bubbling, steaming. “Really? Really? Reeeaaaaally? I think you do. A part of you knows this is where you belong. Right in the middle of the shitstorm. Your heart races. You feel awake and alive in ways you never did before. When you got wrapped up with saving your big trucker boyfriend a few years back, you woke up. You found you had power. Riverbreaker— the stone that parts the waters. Fate’s foe— the one who can slap away the Reaper’s hand. You got used to it. You started to like it. And you like all of this, too.”

Miriam lurches up. She hard-charges to the front and jams her knife in his neck. “I don’t. You’re lying.”

Wade giggles and gurgles. “So violent. Like a feral cat. We like that about you, Miriam. You get things done. We hope you stay on board with us for a long time. We’d hate to see you go. Though we do have one helluva severance package for you when the time comes—”

A sound comes up out of her like she’s dead-lifting a refrigerator, and before she knows what’s happening, she’s plunging the knife in and out of Not-Wade’s face, stitching the blade from chin to brow—

Her eyes refocus.

She’s just stabbing the seat.

Because the Trespasser isn’t real. Or, at least, isn’t a physical being. Maybe a hallucination. Maybe a ghost, or a demon, or some part of herself projected. Maybe her dead child, stolen from her by a woman with a red snow shovel, a dead child grown up into a proper specter and haunting his terrible mother.

Miriam paws for the keys in her pocket and starts the van. If she’s going to have a conversation with somebody, it’s going to be someone real.

INTERLUDE

KEY WEST

“You’re fucking kidding me,” Gabby says.

“Not so much,” Miriam answers. A bottle of Blue Moon beer, slick with condensation, hangs in Miriam’s hand, her fingers forming the spider legs that cling to the neck of her prey. Gabby watches her drink it. Every time she takes a sip, she makes a face. Miriam does not seem to like beer.

“You think I’ll go with you? Are you out of your gourd?”

Miriam shrugs. “At least a little. Maybe all the way out of my gourd.”

The two of them sit on the porch of Gabby’s house, asses planted on white wicker furniture like they’re a pair of genteel ladies instead of the two unnatural disasters that they are. Miriam just showed up here. She just fucking showed up, and did she go for the small talk, Hey how are you what have you been doing sorry about your scarred-up face, Gabster? Hell, no. She jumped straight into the piranha waters with Hey, wanna go on a road trip with me?

Thing is, any time Gabby looks at Miriam, all she sees is her own life reflected back in a mocking reminder: a dog-eaten puzzle with half the pieces missing, a world broken by the earthquake that was Ashley Gaynes and his knife. Ashley Gaynes, made who he was because of Miriam. And now Gabby, made who she is bec

ause of Miriam too.

Every cell in her body is trying to free itself from its prison and run the other way. Miriam once said she was like a poisonous animal with all its strange colors acting as a warning sign: Gabby looked it up. It’s called aposematism, which she thought had something to do with Jewish people, but it’s a scientific term for exactly what Miriam described— bright colors painted in warning.

“You want a cigarette?” Gabby asks suddenly. It’s weird to feel like Oh, I’m being rude, because Miriam is the spiritual manifestation of rudeness. Maybe Gabby is trying to do the opposite thing and show Miriam what it’s like to be an actual human being. “I don’t smoke, but I might have a pack around here. Weed, too. Or a Cuban cigar if you want to chomp on a dog turd—”

“I don’t smoke anymore.” The way Miriam says it, though, all her body seems to shrivel up like a dying bug. Maybe it’s not a lie, but Gabby thinks the woman wants a cigarette bad enough to stab somebody. “I’m trying to do better. To be better.”

“Oh.”

“Oh? You said that like—”

“I said it like what?”

“Like you’re not hopeful.”

“No, it’s just— you’re you. You don’t seem like the type to change. You were pretty comfortable with who you are. Or were. Or whatever.”

“Well, I’m trying to fix some fucked-up stuff.” The way Miriam says it, she’s angry now. Defensive. If she were a dog, the hair between her shoulders would be bristling like a brush.

Gabby feels unexpected disappointment. Which is twisted, isn’t it? She should applaud Miriam’s efforts to be a better person. She should be throwing her a parade with big trumpets and crashing cymbals and a whole float that says THANK YOU FOR NOT TRYING TO FORCE THE WORLD TO DEAL WITH YOUR TOXIC BS. And yet, Gabby admired Miriam for knowing exactly what she was and leaning into it, even if what she was happened to be a drunken clown car crashing head-on into a tractor-trailer carrying beehives.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

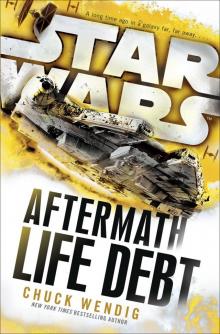

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt