- Home

- Chuck Wendig

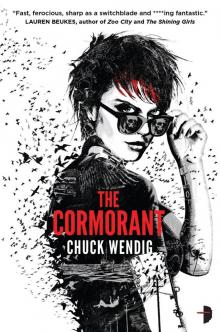

The Cormorant

The Cormorant Read online

Chuck Wendig

THE CORMORANT

To all the foul-mouthed miscreants and deviants who are fans of Miriam, and who make this book possible.

PART ONE

FILTHADELPHIA

INTERLUDE

NOW

“And the Lord said, let there be light.”

A flutter of black fabric, and the hood is gone.

Miriam winces. Blinks. A white wave bleeds in from the edges. The world presses through the blur: shapes emerging from a puddle of milk.

The fat man who spoke sits across from her. Behind him walks the brittle woman, his partner – a boozy, tilted smile stitched between the moorings of two sharp cheekbones. Her hand is bandaged.

“You look like shit,” Grosky, the fat one, says after a low whistle.

“You look like a track suit wrapped around a bunch of trash bags,” Miriam answers. Her voice feels raw. Sounds raw. Like bare feet torn on broken shells, abraded by sand, stung by salt.

Ragged, ruined, roughed-the-fuck-up.

Grosky just shrugs. Laughs a little. He’s got a soft voice. Though she knows he can turn the volume up when he needs to. The booming timpani in the barrel well of his chest.

He’s got the box. Her box. Right there in front of him. He drums his sausage-link fingers on it. The lid rattles. The padlock judders.

The scarecrow – Vills, Catherine Vills – paces like she’s nervous. Like she’s got something to hide, which Miriam knows she does.

Miriam feels it in her feet as much as she hears it: the tide coming in. Not far away. The hush-and-boom of waves crashing. She looks around. This is just some ramshackle beach hut. Wood walls, leaning against one another as if for emotional support. Thatched roof overhead. Cobwebs hang and sway as a fishy breeze creeps in through open windows.

“Where are we?” Miriam asks.

Grosky doesn’t answer her question. “You want anything?”

“Cigarette.”

“You shouldn’t smoke.”

“You shouldn’t mainline lard and melted cheese. Do you even eat the cheeseburgers anymore, or do you just inject them right into your man-tits?” She tries to mimic said injection, but remembers that her hands are cuffed in front of her, and the shackles are in turn cuffed to the leg of the table. The table is wood. Old. Rickety. She could bust if it if she has to.

But she won’t have to. Not yet, anyway.

“Funny thing about lard,” Tommy Grosky says, “it’s got a bad rap. Demonized with all the other animal fats in the Seventies. But the truth is, it’s the vegetable fats that’ll kill you. Crisco. Margarine. Those, eh, those trans-fatty acids will fuck you up pretty good.” He squeezes a fist like he’s angrily milking a goat’s udder. “Closes your arteries off. Like with a clothespin.”

“That is fascinating.” She squeezes the words like a sponge, lets them drip sarcasm everywhere. “Thank you, Surgeon General Fatty McGee.”

“I’m just saying, things aren’t always what they appear.” He pats his chest. Boom boom boom. “You look at me and think, Hey, there’s a blobby bastard right there. Like if Fred Flintstone ate Barney, Wilma, turned that purple dinosaur into dino burgers. Lift up one of his fat rolls, you’ll see a couple Twinkies hidden away. You think I got an expiration date coming up. That my heart’s like a soup can in an old lady’s pantry: sure to burst before too long. But see, here’s the thing: I’m a forty-two year-old guy who’s as healthy as a sixteen year-old. My good cholesterol is through the roof. My bad cholesterol, shit, I don’t even think I have any. Great blood pressure. Perfect blood sugar – I don’t even know how to spell diabetes. I eat well. I like a lot of greens. Chard. Kale. Spinach, obviously.”

“Obviously.”

“So maybe don’t be so smug.” His mouth hangs open. He waggles his tongue between the two rows of flat Chiclet teeth. It makes a wet, hollow sound. “Because maybe you don’t know what you’re looking at.”

“Maybe you forget, I know how you’re going to die.”

His eyes sit tucked behind folds of flesh that look like someone is pinching the skin shut, but suddenly the eyes go wide and she sees something flash there in the dark of his pupils: anger, bright white, like light trapped in the steel of a knife blade.

“This again,” he says. “Right. I’ll play. So you’re saying it’s my health that kills me? If you can even do this thing that you say you can do.”

“What time is it?” Miriam asks. Her turn to change the subject.

Here Vills looks down at a nice watch. A new watch. Movado. It hangs on her gaunt bone-knob wrist near a bandage. Miriam thinks, We’ll get to all this soon enough.

“Five after noon,” Vills says. A smoker’s voice. A voice that’s all rust flakes and precancerous nodes, all in the dry thatch eaves of the woman’s scratchy throat. Then Vills drops a cigarette on the table between Grosky and Miriam.

Grosky gives his partner a look.

“Let her smoke,” Vills says. “Let’s get this over with.”

“Fine,” Grosky says. He flicks the cigarette over toward Miriam. It rolls and she catches it: a trap-door spider leaping upon its prey. Vills hands him a lighter but he doesn’t give it over. He twirls it. Grinning.

Miriam screws the cigarette between her lips. Teeth on the filter. Tongue rimming the paper. She wants it. A nic-fit threatens to tear through her like a pack of starving dogs.

Grosky leans across. Strikes the cheap gas station lighter – flick flick flick. Just sparks, just empty embers, hollow promises, no flame.

He shrugs. Pulls the lighter away. “Oh well.”

“Try again.”

“I’m not breathing in your stink. I gotta do it with this one–” He jerks a thumb toward Vills. “But I don’t gotta do it with you.”

“I have had a bad couple of weeks,” Miriam growls.

“Ooooh. Ho, ho. I know. We’re gonna talk about that.”

“I want my cigarette.”

“You tell me some of the things I want to know, maybe you’ll get that cigarette. And maybe I’ll fix you a plate of greens – it’s good for that sunburn. And – and! – maybe you’ll get out of those cuffs, too. Or maybe not. Everything depends on you, Miss Black.”

“Miss Black? So formal. Please. Call me Go Fuck Yourself.”

“I want to know about this boy,” Grosky says, grabbing a photo from a folder in his lap. He slides it across the table. Soon as she sees it, it’s like someone yanks something vital right out of her. A child’s hand jerking the fabric from a doll’s chest.

The young man in the picture is dead.

Puffy green Eagles jacket spattered with blood.

Blood is black in the winter slush.

Outside the hut in the here and now, the tides rumble.

Somewhere, seabirds squawk and chatter.

Gannets, maybe, Miriam thinks.

Miriam draws a deep breath.

And she tells him the story.

ONE

PUT A RING ON IT

The engagement ring is burning a hole in Andrew’s pocket. That’s how it feels, like it’ll burn through the fabric and drop off into the dirty snow of the sidewalk, maybe roll into the sewer grate and disappear into the slurry below. And if that were to happen, how would he feel? He’d feel horrible. He loves Sarah. He wants to marry Sarah. But he can’t marry her with this ring. A ring too big for her perfect porcelain fingers. A big ring with a diamond too small. A ring he inherited from his mother.

Still. The ring’s like a loaded gun. He’s almost proposed five times in the last couple weeks. Part of him thinks, Just propose, you can get the ring resized, get a new diamond later. Before the wedding. Which won’t be for a year anyway. Oh, God, unless she wants to get married soon…

But no. He h

as to do this right. Her father thinks Andrew does everything half-ass. And her father means the world to her. Andrew has to make this a good show. The ring has to impress her, but more important, it has to impress her father. The problem: even Sarah doesn’t know how bad Andrew’s got it right now. He’s got a good job at a brokerage here in Philly, but he’s thirty thousand in credit card debt. Not to mention the car loan. And the student loans from b-school and from grad school. And the rent. The gas bill. The trash bill. The this bill. The that bill.

He’s got a little money in his pocket but, really, he’s broke.

Which is why he’s out here now. In Kensington at quarter till eleven on a Wednesday night. Walking through a pissy wet snowfall – fat, clumpy flakes not drifting so much as plopping to the earth. His nice shoes white from the road salt. His socks wet from the slush.

Derek at work said, “You want a diamond cheap, I know a place.” Derek said, “It’s in Kensington.” and Andrew said, “Oh, hell no, Kenzo? Really?” He said that if he goes down there, he’ll get stabbed. Or strangled. “Isn’t the Kensington Strangler still around down there?” Derek just laughed. “That’s old news. Crime’s down. It’s fine. You want the diamond cheap, or you want to pay jewelry store prices?”

Andrew thought but did not say, “I want to pay jewelry store prices.”

He just can’t afford to.

And so, a pawn shop. Derek said, “It’s called K&P Moneyloan Pawn, except they don’t speak a lot of English and they misspelled Moneyloan so it says Moneylawn, so at least you’ll know you have the right place.

Andrew thought he’d get there right after work, 6, maybe 7 o’clock. But suddenly the team of in-house lawyers demanded a new meeting at work, and meetings are like black holes: they eat up the hours, they suck in the light, they gorge on his productivity. Next thing he knew, it was past 10 o’clock and he still had to get to Kensington.

The pawn shop was still open. Thank God.

The guy behind the counter – a guy Derek said was Indian (“Curry Indian, not Wounded Knee Indian”) but that Andrew thinks is Sri Lankan – showed him the diamonds and everything looked good; the prices were low enough he almost wondered if they were real, and there he had a small panic attack because wasn’t he supposed to remember something about the three Cs? Color, clarity, cut and… was there a fourth C?

Crap! Whatever. He’s no expert. Neither is Sarah. He picked a princess-cut diamond that looked – well, it looked pretty. It caught the light. It felt heavy. Sharp, too, like it could cut a hole in the storefront window.

So there he stood in a dingy, cracked-floor pawn shop, the too-bright fluorescents above humming and clicking, neon lights trapped between the pawn shop window and the big metal grate just inside the windows, and finally he managed to argue the little Sri Lankan man down to a price he could afford (a price less than half of what he’d pay anywhere else), and then he whipped out his Visa and–

“No credit card,” the little man said.

“I have a debit card–”

“No take, no take.”

“But that’s what I have.”

The little man pulled back the small cloth with the diamond on it. “Cash only. No diamond. Only cash. No diamond.”

So he asked, “Is there an ATM machine around?”

“Is just ATM,” the little man said. “No ATM machine. ATM mean Automated Teller Machine. You no need to say extra machine.”

This from a man whose store is named Moneylawn.

Andrew said fine, fine, just tell me where, and he thought – hoped – that the ATM was right across the street, but no, of course it wasn’t, it was three blocks up and four blocks over and now the sky is really flinging the glops of wet snow down on his head as if to punish him for his bad money management–

So now here he is. Hurrying along. To an ATM in the middle of Kensington. A neighborhood no longer in decline because it can’t decline any further – the car has already crashed, the wreck has already burned out.

Derelict storefronts. A lone pizza joint at the corner, still open. Eyes watching him from under a ratty overhang. Past an alley where a homeless guy in an overcoat sleeps in the shade of a dented dumpster, using a blue tarp as a blanket. Someone yelling a block over – a Hispanic girl in a half-shirt and jeans, no jacket, no hat, bronze hair peppered with white flakes, and she’s screaming at some little thug in a leather jacket, saying something about sucking his dick, something about someone named Rosalita. The thug’s just laughing. Braying, even. Waving her off.

Andrew keeps his head down.

Turn around. Go home. The diamond will be there tomorrow.

No. Tomorrow is Saturday. He and Sarah are going to Wildwood Gardens. She loves that place. The orchid house. The Christmas lights. He’s going to ask her there. Do the whole thing: down on one knee, ring up, maybe in front of a crowd so they have that story to tell.

Just walk. Hurry up. You need to do this. Man up, Andrew. What would her father say?

Her father would say nothing. He’d just stare at Andrew with those dark gray eyes, eyes like bits of driveway gravel.

Ahead – a basketball court. Tall fences. Three courts lined up next to each other. He can shortcut the block, he thinks.

But then–

Footsteps. Behind him. Crossing the street. Splashing in slush.

He casts a quick glance over his shoulder.

A shadow following. Hands in pockets. Dark camo. Hood up.

His heart starts kicking.

He hurries forward. Half a short block to the basketball courts. His foot catches on an uneven sidewalk – he falls forward, just barely catches himself, but he takes the opportunity to shift into a brisk walk, almost a jog.

But the person behind him is coming up fast now.

Faster than he is. A swift step.

The person raises a gloved hand. Points a finger-gun at him.

The thumb-hammer falls.

Andrew hurries. Grabs the pole holding up the chain-link leading into the basketball courts. He ducks in through the gate–

“Hey!” calls a voice.

A woman’s voice.

“Andrew!”

She knows his name?

Thud. Something hits him hard in the back.

Snow plops.

A snowball. She hit him with a snowball.

He wheels. Holds up both hands, palms forward. “I don’t know who you are or what you want, but I don’t want any trouble–”

The woman hooks her thumbs around the hood, flips it back. It’s some white girl. She shakes free a shaggy ink-black pixie cut, the front bangs streaked with red. She stares at him from raccoon-dark eyes.

“You dumb shit,” she says, baring her teeth from behind a fishhook sneer. “What are you doing out here?”

“Wh… huh?”

She sighs as snow falls. “I don’t know why I’m yelling at you. I knew you’d be here. Isn’t that why I’m here?” She taps a cigarette out of a rumpled pack of Natural American Spirits. Cigarette between lips. Clink of a lighter. Flame in the winter. Blue smoke.

He coughs. Fans the smoke away.

“I gotta go,” he says.

“You don’t remember me,” she says. A statement, not a question.

“What? No I–” Wait. The way one she stares from under an arched and dubious brow. He knows that look. A look of unmitigated incredulity. A mean-girl look like she’s saying, You’d really wear those pants with that shirt? Sarah gives him that look sometimes. Her judgey face. “Yeah. Hold up. I remember you. From the bus.”

She gestures at him with the cigarette. “Got it in one.”

A year ago. On the SEPTA NiteOwl route home to University City.

His stomach suddenly drops out from under him.

“You… told me…” He tries to remember. He was tired that night. No. Drunk. He was drunk that night. Not black-out-and-wake-up-in-Jersey drunk, but drinks with Derek and the other brokers… Did Sarah yell at him that night? No. They were only

just together then. Not even living with each other. They’d just met.

The woman vents smoke through her teeth. “You have a ring in your pocket. Left pocket, I think.”

His gaze darts down. His hand reflexively touches the pocket. There the ring is heavy. The One Ring, he thinks. On the way to Mordor. Absurd that he’s thinking about that. He doesn’t even like those books.

“How do you…” But then it all hits him. Ice breaking. Water rushing. The memory cold as the slap of the winter air.

On the bus. He’d seen her there before. Sitting in the back. Earbuds in. Then one day she came up to him. Sat behind him. Started talking. He’d had… what were they? A bunch of Long Island Iced Teas. How do they get them to taste so much like iced tea? They turned her into a smudgy blur, a Vaseline thumbprint on the lens of his life.

She just started talking. Like she couldn’t stop, like someone karate-kicked the spigot right off the sink – words spraying everywhere. She was amped, jacked up in the same way he was slowed down, and she told him–

You’re gonna die.

That’s what she said.

She knows about the ring now because she knew about it then. Didn’t she? She told him he’d have a ring in his pocket, and he said that was absurd. At the time he hadn’t even thought of marrying Sarah, but here he was, with a ring – his dead mother’s own engagement ring – there in his pocket, a modest little circle of white gold, too modest…

The girl gave him a date. Told him to “mark his calendar.”

Was tonight that date?

He doesn’t even realize he asked the question out loud.

“Yes. It’s tonight, genius.” You really should’ve written it down. I told you to write it down. I said, ‘Whip out your fancy smartphone and write it the fuck down.’ But did you? Mmm. No. You just puked on your shoes.” She suddenly pauses, as if in rumination. “OK, maybe I should have waited till you weren’t drunk to give you the news, though at the time I thought it might soften the blow. I’d been watching you for days. I brushed by you on a Monday, didn’t tell you until Thursday.”

“You’re crazy,” he says, backpedaling.

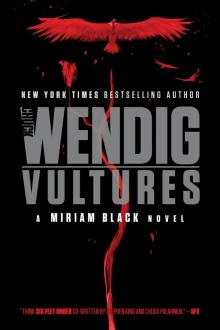

Vultures

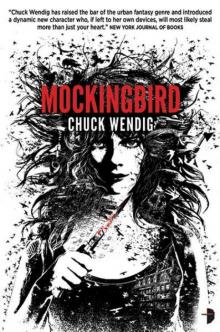

Vultures Mockingbird

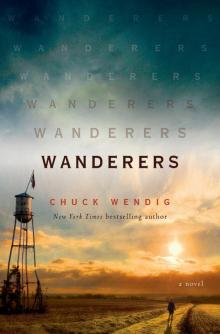

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

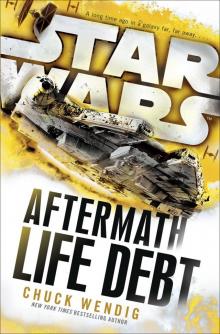

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt