- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Thunderbird Page 10

Thunderbird Read online

Page 10

“I’m here to see Mom,” Miriam says. “Deal with some of her stuff. Then I’m back on the road again and . . .” She swigs at the beer, makes another face.

“You said you’re looking for someone?”

“A woman named Mary.”

Gabby arches an eyebrow. “What does Mary have for you?”

“Mary is going to fix me.”

“Fix you?” She almost laughs. “Okay. Sure.” Her hand instinctively moves to her face, feeling the puffy ridges of scars there, like the solder in stained glass. Gabby stands up suddenly and says, “The last time we did this thing, it was fun and— you know, whee— but I don’t want to Thelma and Louise with you again. I can only go over so many cliffs.”

Miriam stands too. “I don’t need you that way.”

“What way do you need me, then?”

“I need— I want a friend. Okay? We could be friends.”

“When you and I get together . . .” Gabby frames her scarred face with her hands like she’s a film director framing a shot. “Ta-da.”

“Yeah. No. You’re right. Totally right. I don’t blame you. I’ll leave you alone. Have a good rest of your life, Gabs.” With that, Miriam starts to step off the porch. Gabby says to Miriam’s back:

“Good luck with this . . . woman you want to find. I hope she fixes you.” Her brow wrinkles up. “Though I’m at a loss how another woman will fix you.”

Miriam turns slowly. “You don’t know, do you.” A statement more than a question. “Of course you don’t. I never told you.”

“Told me what?”

“I have this . . . power. A gift, a curse. And this thing?” A long sigh escapes Miriam’s lips. She bares her teeth— the signs of a nic-fit, maybe? “This thing has rules.” Then she tells Gabby a story. A strange story. An impossible story.

And a story that helps it all make sense. A special kind of sense. But it’s like scattered pieces brought together to make a picture.

Soon as Miriam’s done telling the story, Gabby decides. She makes the decision because she has to know more. She has to know if it’s really true. And if it is true, then what Miriam Black goes through on a day-to-day basis is a horror show unlike anything Gabby could have imagined.

Gabby tells her that she hates Florida and she wants to leave.

“Let’s go on a road trip together, Miriam Black. As friends.”

“As friends.”

And their fates are sealed with a handshake and an awkward hug.

TWENTY-FOUR

SWEPT UP IN A TERRIBLE WIND

She parks the wizard van at the Motel 6. The sorcerer cooling his heels, the dragons frozen in place, the battle between them ongoing and eternal.

She takes a moment to compose herself. An odd action for her. Since when do I care what other people think of me? Is that what this is? Is it a strength or is it a weakness? She can’t tell. Fuck it. She heads upstairs to their room.

Already as the door starts to drift open, she knows something’s wrong. The way it feels. The air in the room: still, too still, too strange. Every molecule unsettled.

Before the door is all the way open, she’s got the knife back out— blade flashing with the snap of the wrist.

A man sits on the edge of the bed.

Broad shoulders. A two-day beard growth— scratchy and rough, like you could clean your boot on his chin. A disarming smile in the midst of it.

He leans forward, hands on knees. “Miriam. Come in.”

She knows that voice. The man from the phone.

“Where is Gabby?” Miriam snarls.

“Your friend is fine,” he says. A pistol sits on his knee, covered mostly by the flat of his hand. She curses herself: the other gun, the one she stole, is still in the damn van. Shit.

“How’d you find me?”

He hesitates. “That’s my little secret.”

“Fuck you and your secrets. You’d better talk quick because I’m rattlesnake-fast. You’ll point. You’ll shoot. But by the time I flop over dead in your lap, you’ll have my knife sticking in the side of your neck.” Everything feels like it’s pulled taut— a choking rope, a fraying wire, a bow dragged slow across violin strings. She points the knife at him with a shaking hand. She cuts the air with a castrating swipe: swish swish.

“Settle down. I want to be friends. My name is Ethan. Ethan Key. Why don’t you close that door so we don’t attract any other new friends?”

She hesitates. A part of her thinks, Just run. Stable door is still open. She could bolt like a coltish horse. Gabby will be fine. Once they know she’s hit the trails, they’ll ditch her. Or cut her throat and dump the body. Or burn her up like they burned Wade. Goddamnit. Goddamnit!

With her heel, she gently eases the door shut.

The lock engages.

All parts of her hum like wasp wings.

Ethan says, “Things have changed. I figured you for a fly in the ointment, but now I’m thinking different. Wade seemed to think so. Said you knew things about people. Things nobody else could know.”

She stiffens. “Wade told you that.”

“In a manner of speaking.” That disarming smile flinches a little. Twitch, twitch. “I have an interest in people like you.”

“Bitches with knives?”

“People who can change things. Change the whole world, even.”

“You got the wrong girl. Whatever he told you, Wade was just selling you a story. Maybe if you wouldn’t have tortured him and killed him—”

The man stands. Hand curled around the gun. “Wade was not a good man. I don’t blame you for letting him die the way you did. He once raped a girl; you know that? High school. The school covered it up, no conviction.”

Through clamped teeth she says, “You’re lying.”

“Telling you the facts as I know them. I believe in being straight with people. Honest to a fault.” Ethan shrugs. “Truth is hard. Most people who you think are good often aren’t. I suspect you already got that part figured out.”

You have no idea.

“And I’m supposed to trust you?”

“No. Not yet. But you are going to come with me.”

“Eat me. You try to take me anywhere, I’ll scream. I’ll cut you. I’ll scream. It won’t end well for anyone.”

“Including your friend Gabrielle.”

It’s just Gabby. Asshole. “Here you’re trying to sell yourself as a white knight, then you go and threaten my friend.”

He takes a step closer.

“No,” he says. “I’m not a good man. I am, in fact, a bad one. But even bad people can do good things, and I’m hoping you get that. You’ll see it in time. You’re going to come with me because we have your friend, and if not that, because amongst my friends and my family are others like you. People with powers. People who can change things.”

And then he turns the gun around, lets it swing loose with his finger curled around the trigger guard. Ethan urges the gun toward her, grip thrust first.

She sees the round knobby curve of his thumb knuckle thrust up. A tantalizing piece of skin. Touch it. See how he dies.

“What is this?” she asks.

“It’s my gun.”

“No doy, asshole. Why would you give it to me?”

“A peace offering of sorts.” Then he laughs a little. “That’s a strange offering, I suppose. A gun as a symbol of peace? These are curious times and we are unusual people, you and I. So, maybe it’s fitting.”

She takes the gun. He pulls his hand away before she gets that sweet skin-on-skin contact. No vision. No death. But that’s okay, though.

Because she already knows how he dies.

She spins the gun around.

Points it at him.

Pulls the trigger.

TWENTY-FIVE

BREAKERS

Click.

Click click click.

Shit!

“If I had that pistol loaded up, you would’ve jeopardized everything. Your fr

iend. My life. Your own, inevitably. Just because you can’t control yourself.” Ethan sighs, clucks his tongue. “You are indeed a wild horse in great need of breaking. That’s all right. We’ll get there. I have a gentle hand.”

“I do too,” Miriam says, and gives him the finger.

His smile finally falls away.

“Let’s take a ride,” he says.

PART THREE

* * *

THE BAD LANDS

INTERLUDE

YOUNG MIRIAM

Miriam is eight years old.

Lightning flashes. Thunder rattles the old house a half-second later. Rain hammers the window glass like it’s desperate to come inside, like the only thing it wants is to drown them all.

Miriam cowers under the covers.

She tries not to cry. But sometimes, she makes this sound in her chest, a sound that rises up out of her lungs and her heart, a sound like an injured animal— a bleat, a cry, a wail she has to cut short and bite back.

Another pulse of lightning. Another teeth-rattling bang of thunder. Like dynamite going off on a too-short fuse. Flash, boom. Flash, boom.

The thought, tantalizing and forbidden, keeps circulating like a dog chasing its tail: Just get up. Go tell Mother. Tell her you’re scared.

No, no, no, no.

That won’t work.

That never works.

Flash, boom.

She cries out again. A throat-cut sound.

Before she even knows what’s happening, her bare feet are landing on the cold wood floor of the room, and the blanket is trailing behind her and she knows, she knows, no, no, no, stop now, turn around, no good can come of this, no way, no how, but still she keeps going. Past the one teddy bear on her shelf with the dangling button eye, a shelf with books she hates to read: the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Crime and Punishment, A Tale of Two Cities, and some old Russian children’s book, with monstrous Constructivist humans showcasing their weird Russian jobs (and smoking), none of it in English, all of it in Russian. Past the crucifix on the wall with the poor, scary man named Jesus who hangs there, bleeding. In the hallway, past the mirror hanging there crooked, past the heating vent on the floor that tinks and tonks and bangs when the heat comes on.

To Mother’s door.

Don’t knock don’t knock don’t knock.

She raises her hand to knock but holds it there in the air, like she’s holding onto something invisible and just can’t let go.

It won’t work. It never works.

Deep breath, in and out.

With no small amount of sadness and fear, she decides to go back to her room.

But Mother’s door opens. Suddenly, swiftly— startling her.

And there stands Evelyn Black. Scowling down, each of her hands clasping its opposite elbow, rubbing the skin there. A black shape, blacker against the dark room behind her. Her mother utters a disgruntled hnnh.

“Don’t think I didn’t hear you,” Mother says.

“I’m sorry.”

“In your room, caterwauling like a cat. You should be ashamed. It’s just a storm. You’re eight. Not four. Not a diaper baby.”

“I just, I just . . .” She hears herself stammering and it makes her feel even more shame and more embarrassment that she can’t even manage the words. But somehow they tumble out: “I just want to see if muh-maybe I can come in? And sleep with you. Just tonight. The lightning is really—” As if on cue, a flash hidden in part by the lack of windows in the hall, but a swift splitting of the air afterward. The mirror down the hall rattles against the plaster. “It’s close.”

“And you’re scared.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Scared as if the lightning might grow hands and reach in through the window. Snatch you up. Drag you out into the rain.” Miriam hadn’t quite thought of it that way, before, but now that she was . . .

“I don’t know. It’s loud and scary.”

Mother grunts. “Life is loud and scary, Miriam, dear. The dark comes every night. Storms come every season. No comfort I can give you will change what’s coming. It is up to you to stand against it because it is what it is, always and forever. We must trust in God to grant us the steel and the salt to push back fear. If we are good to God, then He will be good to us and give us shelter and courage.”

Tears well. “But, Mother—”

“No. No more crying or I’ll take your blanket away and give you nothing to hide under.”

“Can I . . . can I have a flashlight, at least—”

“The lightning will be light enough. You have a roof over your head and God’s plan. You need nothing else.” Her mother stiffens. “Don’t make me angry, Miriam. Go. Go now, and let me sleep.”

Miriam hurries back to her room, trying not to weep.

The lightning flashes, and thunder booms.

In the morning, they will discover that lightning hit a tree in their front yard. Thirty feet from the house.

The tree stands split down the middle, as if cleaved by an axe.

TWENTY-SIX

THE VALLEY OF THE SHADOW OF DEATH

The mountains sitting at the base of the sky look like torn paper—ripped into jags and peaks by untrained or uncaring hands. Or maybe it’s the sky that looks like paper. Miriam can’t tell, her gaze swallowed by the horizon. A brown world the color of a grocery bag. Little scrub bushes here and there: creosote and palo verde shouldering their way up and out, branches reaching for one another (but never touching), like a kingdom of doomed lovers.

Miriam’s hands grip the steering wheel of the wizard van, knuckles gone bloodless. Fingertips tingling, the tension all the way down the elbows.

Ethan sits in the passenger seat, staring out. He made her take the van to get it off the road— said cops other than his friend might be looking for it.

The highway ahead is long and mostly empty. A car or truck passes on the other side every couple of minutes. A horse trailer. A pickup. A Jeep.

“I could drive this car off the road,” she says. “Just cut the wheel, hit some Mack truck coming on the other side. Wipe us both out.”

Ethan shrugs. “You want to do that, that’s your right.” But he sits up straighter, probably because he remembers how handing her a gun went. The gun that once again sits on his knee, this time its barrel almost nonchalantly pointed at her, his finger curled around the front of the trigger guard. “I figure you won’t. You’re in this deep already. Might as well at least take the ride to its end, see what waits on the other side.”

“I want you to know, if you hurt Gabby . . .”

“We did not hurt her.”

“But if you did. Hypothetically. Or hell, maybe you hurt her feelings. Maybe she stubbed her toe on the way in. That happens, dude, I will repay the slight a thousandfold. You picking up what I’m putting down?”

“We’re not so different,” he says.

“Oh, god, here it comes. Classic villain talk.”

“You protect your loved ones with tooth and claw. So do I. That’s what all this is about. Protecting what we love. You’ll see.”

A sedan passes going the other direction. All the muscles and tendons in her arm ache to jerk the wheel. Head-on collision. Maybe I’d walk away from it. She’s a survivor. But maybe this guy is too.

“You all say the same shit. We’re not so different. You justify what you do as something good because nobody thinks they’re the bad guy. You all think you’re the heroes of your own story—misunderstood underdogs who know how things really work, and if only the world bent to your horrible will, everything would sort itself out. Truth, justice, and McDonald’s cheeseburgers for all.”

He laughs— a genuine thing, that laugh, as disarming as his smile. “I bet you think you’re the good guy too.”

“I dunno.” Hell, yes, I’m the good guy. “I don’t think about it.” Am I the good guy? Oh, shit.

“Here’s what I think,” he says. “I think that good guys and bad guys is too simple a thing, Miriam.

I think we’re all on a spectrum of gray, and each of us is capable of very good things and very bad things, and we are sure to do both in our lifetime. Best you can do is have a code, a set of rules, and stick to it. I am willing to do bad things to achieve good. That’s my code.”

She rolls her eyes. “Here’s a wacky idea. Why not trying to do good things to achieve good? Give to the poor. Save a kitten. Say nice things to old ladies. What a kooky code that would be.”

“That what you do?”

“What I do isn’t send snipers to shoot a mother in front of her child.”

He sits up straighter. “I was wondering if we’d get to that.”

“What I do isn’t burn a man inside his own gas station.”

Ethan shrugs.

“What I do isn’t blow up buildings.”

There. That one. A little arrow plucked from the future and fired right into his eye. Thwock. But there he gives pause. His brow furrows like a plowed field. “That woman we were pursuing, she was a danger to her own child, and I cannot abide danger to children. Wade, well, I already told you: he was a rapist at the college where he worked. But that last thing? We haven’t blown up any buildings.”

Yet.

Though he does seem genuinely bewildered. That’s a kink in the hose she can’t quite work out.

He says, “We’re not terrorists, Miriam.”

“You keep saying that. We. Who’s we, Key? The Coming Storm?”

He sighs, and the smile slowly returns to his face: slow as a sunrise, slow as an ice cube melting, slow as cold honey.

“That,” he says, “you’ll see soon enough. Keep driving.”

TWENTY-SEVEN

LIMITED PATROL AREA

She drives for a couple hours. South through a few small towns of shitty little houses and boarded-up churches. Eventually, the afternoon sun hangs in the sky, its head hung low, the bleach-smear of a star drifting sluggardly down toward the horizon like it just can’t do it anymore— as if even the sun is tired of the heat and it just wants to find a shadowy place to hide and sleep.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

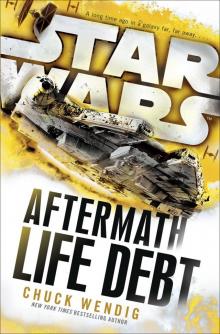

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt