- Home

- Chuck Wendig

The Hunt Page 3

The Hunt Read online

Page 3

A warning goes off in her head: You need to take this seriously, girl.

The dam breaks. She hops up and casts her foot under the bed. Atlanta hooks the tips of her toes around the Winchester .410, slides it out, and picks it up. It’s already loaded. Because of course it is.

Then she’s marching forward, gun up—she’s creeping forth on the balls of her feet, breath held in her chest as if to let go of it is to die. Thumb on the hammer of the single-shot, easing it back with a soft click—

In the hall, she hears it. Whispering.

Is it real?

Or all in her head?

No time like the present to find out. She whips open the door, the barrel of the gun thrust forward—a square of bright light there in the darkness, floating like a tiny window. A whoop of fear rises up. A man’s voice: “No!”

Atlanta thinks, Pull the trigger.

But then, her mother’s voice yelling, “Atlanta! Atlanta, wait!”

Her hand flies to the plaster wall in the hallway—there she finds the switch and she flips it on. A man stands revealed in front of her, stubble-cheeked, lean, a little rangy like an underfed hound. He’s got a phone in his hand—like he was using the light from it to navigate his way upstairs.

Behind him on the steps is Arlene Burns.

Her hair’s all a-frizzle. Coming up with her are the mingled stinks of fresh cigarette smoke and stale beer. She’s got two more beers in her hands, Yuengling lagers. The pair of them—Arlene and what must be her new beau (suddenly Atlanta can guess at what her mother has been hiding)—stand stock-still on the steps like a couple of raccoons caught in the beam of a flashlight.

“Atlanta, baby,” Arlene says, her words mushy like gravy-soaked bread. “Put that gun down, ’kay? It’s just me and my . . . friend, Paul, here, and—”

“Goshdangit, Mama,” Atlanta growls. “Shit!”

Then she backpedals into her room and slams the door hard enough that the whole house rattles and shakes with it.

Arlene tries for a while, knocking on the door. “Baby. Baby. Sweetheart, open up. Let’s talk this out real quick, okay? Super quick.” Then, a fast turn into parental authority, something Mama’s never been particularly good at: “Atlanta, I said to open this door right now. Right now. Come on.”

A show for Paul, probably.

Atlanta locks the door.

Turns out the light.

Eventually, Mama drifts away like a dead frog pulled toward a pool filter.

Atlanta hears murmuring from the hallway or another room: Paul and Mama talking. About what just happened, probably. About her.

Atlanta hopes that Paul pissed his Wrangler’s. Not getting laid tonight, she thinks. It’s cold comfort for a long, sleepless night.

Sometime late, or maybe it’s early, Atlanta thinks:

I need to go see Guy tomorrow.

I need new drugs.

CHAPTER THREE

The smell of bacon might be supernatural. You got a dead man on the ground in front of you, cook some bacon—the smell might wake him up.

But no matter the magical properties of salted, cured, smoked pork belly from the Amish market, Atlanta Burns is in no mood for it. Her stomach whines like Whitey does when he gets a bone stuck under the ratty pull-out couch, but her head and her heart aren’t having any of it. She stays in her room long as she can, putting her books in her book bag. Time keeps on ticking, though, and soon she’s either gotta go or gotta skip school, because Shane will meet her at the end of her driveway in about ten minutes. Maybe I could skip . . .

No. Too many eyes on her right now.

One thing Holger had right: she has to get out of this thing alive. And even more important than alive is graduated. (Though even now she thinks, I could just get a GED. Is school really that essential? But she shoves that thought away.)

Downstairs, then.

In the kitchen, Arlene has her head buried in her folded-up arms. It’s not her doing the cooking. It’s him. Paul, standing there in pajama shorts and a firehouse T-shirt. He looks over with those sleepy hound-dog eyes and says, startled, “Hi there.”

At that, Arlene’s head perks up. “Atlanta. Hey, about last night—”

“No” is all Atlanta can muster.

Then she grabs the first thing off the counter and ducks out the door.

Of course, what she grabs off the counter is a can of baked beans, and she’s not sure why she grabbed it. She curses under her breath, says good-bye to Whitey (who is outside, taking one of his epic dumps), and wings the can into the nearby cornfield. Whitey runs after the can. Atlanta goes to school.

Wham.

Atlanta jerks her head up and sniffs. “Whuzzit,” she says.

She’s in an empty classroom.

Mr. Lovegrove is standing in front of her desk. He’s holding a book. A history book, as he is a history professor—American history, actually.

“Usually,” he says, nasally and droll, “these books put kids like you to sleep. But turns out, you slap one against a desk, it wakes them up. This book is a multitasker. I wonder what else I could do with it. Hit a baseball. Mash a potato.”

“Hey, Mr. Lovegrove,” she says, her mouth tacky with dry spit. Her words sound like her mother’s this morning: gluey, gooey, still half-drunk. (And suddenly she wishes she really were half-drunk.) “Wha’ happened?”

“You fell asleep.”

Her eyes narrow. “For the whole class?”

“For the whole class. Even through the bell.”

“The bell’s loud.”

“Very.”

“Oh.”

“I think it’s your lunch period now.”

She blinks. Is that right? Wait, yeah, it is. “Okay, thanks.”

As she stands up, Mr. Lovegrove clears his throat—the teacher has a goaty vibe about him, what with the wispy gray beard and the bumpy forehead and the long nose with big nostrils. Looks like he’d be right at home eating a can or munching a mouthful of grass.

“Atlanta,” he says. “You all right?”

“Peachy. Can I go?”

“Before the school year, the vice principal made sure to have a talk with all your teachers. Last year, given . . .” He chaws on it for a minute like he’s trying to find the right words. “Extenuating circumstances, I’m to understand that your teachers all received instructions to give you a B plus across the board.”

“Uh-huh.”

“That grace period is over.”

“It shouldn’t be. I’m still traumatized.” She hears the words come out of her mouth, and therein lurks a paradox, because on the one hand, they’re true. On the other hand, they’re an excuse.

“Be that as it may, the word from on high is, no special treatment.”

“Fine, whatever.”

He leans in. “And you’re not doing well in this class. You’re hovering a hair’s breadth above a D grade.”

“Yeah, fine, I said.”

“That’s okay with you? Don’t you want to do better? Not just sleep through your classes? Through life? What are your plans—”

Oh, good gravy, not this again.

“I gotta go,” she interrupts. “My blood sugar is so low right now it’s like a snake’s belly in a wheel rut. Lunch calls. See you, Mr. Lovegrove.”

She carries a lunch tray through the caf, hair pulled close around her face—a curtain to hide the windows of her eyes. She knows people watch her. They’ve been watching her since she got back from Emerald Lakes last year, but now the look has changed. It’s different. She can’t quite peg how, yet.

Other side of the room, her table. Once, she sat alone, but now she’s collected a beautiful sideshow. Shane, of course, looking primped. Chomp-Chomp (Steven), his hair a mess, the shirt of some local hardcore band—Cold World—hanging loose on his bony frame. Kyle Clemons, the geek with the doe eyes and the puffed-out goldfish cheeks. Eddie Peters, one of Chris’s friends from the La Cozy Nostra gay mafia days—though since this school year’s s

tarted, it seems like they aren’t really much of a thing anymore. Next to Eddie is Josie Dunderchek, who Atlanta was pretty sure is a lesbian—she kinda dresses in this 1950s rockabilly roller derby way—but after the thing with Joey Eckhart, Atlanta’s not so sure anymore. (Shame, she thinks, that Joey has another lunch period. He’d fit right into this crass menagerie.) She doesn’t see Damita Martinez at first, but then—

There she is, at another table.

Huh. She and Shane were getting cozy for a bit. Wonder what happened there.

Atlanta keeps moving. But suddenly, someone pops up in front of her like a deer running in front of a car.

Mandy Newhouse.

Hair the color of the sun on autumn wheat. Lips as pink as a Barbie car. The smell of money comes off her like she’s got fresh-printed hundreds lining the inside of her too-tight jeans, her fuzzy boots, her weird little puffy vest.

“Atlanta!” she says. She’s either feigning excitement or somehow manufacturing the real thing. “You wanna sit?”

One of the popular girls is asking her to sit. At her table. Their table. Kids who belong to the seventh heaven, the UAF (uppity-as-fuck) types with rich, divorced parents and new cars on their sixteenth birthdays and vacation homes either in the Poconos or down the Shore, or even up in the Hamptons. They ski. They have the parties. They have the coke, the Molly, the good prescription stuff.

Sitting there, the usual crowd: the brooding Danny Decker; the cheekbone twins Jason and Joshie Barford; the human tree trunk, Moose Barnes; the pit viper (and some say school bicycle), Samantha Gwynn-Rudin; and of course, two of Atlanta’s once-friends, Petra Bright and Susie Schwartz, both of whom have apparently made it to the Big Leagues now.

All the gang’s accounted for but one:

Becky Bartosiewicz. Atlanta’s first friend in school—a friend who abandoned her once the shit hit the fan and Atlanta took a trip to Emerald Lakes.

“Where’s Bee?” Atlanta asks.

“What?”

“Bee. Becky. Where is she?”

Mandy just gives a snooty shrug and a small laugh, like she knows something. “Well. I dunno. But she’s not sitting here.”

Moose, who’s a linebacker on the football team, looks up from a hoagie and with a mouthful of meat and shredded lettuce says, “What do you care?”

“Moose, shut up,” Samantha says. And he shuts up fast.

At that, from the table, Petra says, “She’s off campus.” And then Samantha shoots Petra a glare, and the girl withers like a marigold after first frost.

You do well in school, you might earn a few off-campus lunches per week. Get in your car and drive somewhere to eat, Burger King or Applebee’s or whatever. Maybe that’s what it is. Maybe she’s off with the likes of Mitchell Erickson somewhere. Dang, wouldn’t they be a pair. Ugh.

Still. Something weird going on here. Atlanta gets the sense that the herd has shouldered together and pushed out one of their own into the wild.

Well, maybe Bee deserves it. She did that to Atlanta, and now they’re doing it to her. Daddy used to say, Sometimes, you gotta eat the cake you bake.

No matter how it tastes.

“Sit?” Mandy says.

“Yeah, no,” Atlanta says, then pushes past her. She figures it for some kind of trick, a trap, a joke—they want her to sit and then they’ll do something to make fun of her, knock her down a peg. And she can’t have that. Even if it was a sincere offer—well, heck, why even entertain that idea? No way it’s sincere.

“Wait,” Mandy says, but Atlanta’s already moved on to have lunch with her friends. Her real friends. The freak-shows, the fuck-ups, those who won’t fail her.

That’s what she tells herself. She has to believe in somebody, because believing in herself just isn’t enough.

Later. Seventh period. She’s in precalculus with Miss Prasse. Math sucks. This one period above all the others pulls the day like taffy—it stretches minutes into hours. And so she sits there, belly full of square lunch pizza, trying again not to fall asleep as Prasse snoringly lazes through sine, cosine, and tangent. Whatever those are. Atlanta’s trying to find some reason she might use these in real life.

She’s coming up short.

Time comes that she starts to drift off again—but before she does, something tickles her brain stem, an old caveman paranoia that tells her she’s being stared at. It tells her that because it’s true. Someone is staring at her.

It’s the new kid. Damon something-or-other.

He’s staring at her with a set of dark eyes. And smiling at her with those thin lips and bright white teeth. He’s one of a few new kids this year—Atlanta was new not long ago. She’s not sure about his story. Maybe it’s a problem with changing district lines. Or maybe he’s like her: the child of a parent who decided to pack up everything and move.

Damon gives her a wave.

“Quit staring at me,” Atlanta says, loud. Too loud. On purpose.

Prasse stops the chalk line across the board. She’s a little thing, Miss Prasse—an itty-bitty skeleton of a woman with hair almost perfectly triangular. She turns and purses her lips. “Atlanta, do you have a problem?”

“Smirkybutt up there won’t quit lookin’ at me.”

“Mister Carrizo, do you have a problem?”

Damon holds up both hands in surrender. “Nope.”

“Good. Now eyes forward. This math is important. You need to learn this for the job market.”

Atlanta almost laughs. Sure, lady. Sure.

He comes after her in the hall. Atlanta winds her way through, trying to get away because she doesn’t like being cornered or followed or stared at.

But he’s calling after her. Damon.

Ahead, she gets blocked by a bunch of kids standing around a bulletin board, ogling it like it’s a brand-new stone tablet huffed down the mountainside by Moses hisownself—looks like some kind of audition results for a musical.

“Move!” she says, trying to push on ahead, but the cows won’t budge, so now Damon is right behind her.

“Atlanta—”

She wheels on him. “What?”

“I just wanted to say sorry.”

“Super. You said it. Bye.”

“Wait! Slow your roll.”

“You don’t tell me to slow my roll. I don’t even know what that means, but I’ll slow my roll when I want to, not when you say so.”

She turns and uses her backpack as a battering ram to push through the theater nerds, knocking them over like bowling pins. But Damon, this kid’s like a burr on a dog’s ass. “I thought you might wanna get together.”

“And why would I want to do that?” she says, not stopping.

“You were new once. I’m new now. I don’t have a lot of friends here. You seem cool and pretty and all—”

Again she stops and again she turns. “I don’t give a hot sack of cat crap whether you think I’m cool or whether you think I’m pretty. What I care about is your ass respecting my ass when I say I don’t want you to stare at me in the middle of class and stalk me in the hallway. Now, I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt and let this go because you’re fresh fish and you haven’t heard the stories. But I don’t do well by men and boys who don’t respect my personal fuckin’ space. You hear?”

He smirks. The asshole smirks.

“I hear you, okay, okay. I surrender.”

But he doesn’t look like he is. That’s not surrender in his eyes. That’s something else. Determination.

Still. When she storms off, he doesn’t follow.

Guillermo Lopez—Guy, or Guy-Lo—sits outside his trailer just outside of town, sipping a Corona with lime and reading a beat-ass paperback book, a Megan Abbott. A few other crime novels lie strewn in the grass near a cooler: Laura Lippman, Joe R. Lansdale, Iris Johansen. He looks up over his beer, sees her coming up the path, and he laughs.

“Hey, ’Lanta, there you are! Been a little while, eh?”

She comes up, grabs another folding beach ch

air, and pops it open. Drops her body in it like it’s a bag of milled flour. Atlanta puts out her hand. “Beer me.”

The clink of bottles until one hits her hand. Wet with ice melt.

Top popped, long sip. “So, hey,” she says.

“Haven’t seen you in . . . well, damn, I dunno. Few weeks. Month or more, maybe. Where you been?”

“School started back up again.”

He laughs. “Oh, ho ho, yeah, shit, I forgot that you do that. I dropped out of school by your age.” He lifts his chin and looks snooty for a second and affects a comical, rich-white-person accent: “I am the proud owner of a GED, I will have you know. Only the very best schooling for me, my dear. The very best.” Another laugh, then a loud gulp of beer. “How is it? School, I mean.”

“Sucks. You know. The usual. It’s like, they teach you a bunch of stuff you don’t really need to know and don’t teach you the stuff you need to know. I mean, who cares which king came after which other king? Tell me how to . . . pay taxes, or fix a toilet, or become a CEO of a major corporation so I can exploit my workers long enough to send my business to China.”

“Normal, basic life shit,” he says.

“Exactly. I’m just talking life skills.”

They both laugh now.

He says, “That dog of yours still keepin’ on?”

“Whitey?” She sips the beer. “You bet. One eye, one ear, head like a package too big for the mailbox but the postman shoved it in anyway.”

“You got a thing for strays and runaways, huh?”

“Birds of a feather and all that.”

The breeze kicks up. Does a little, but not enough, to scatter the heat slicking her brow. The sun’s drifting down over the horizon now; its light is broken by the trees, but its intensity remains whole.

Finally, she says, “I need some pills.”

“Adderall run out?”

She shrugs. “Not on that anymore.”

“No shit?”

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

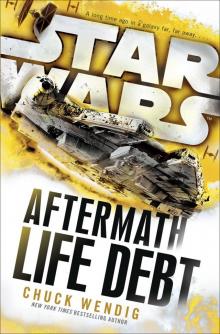

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt