- Home

- Chuck Wendig

The Hunt Page 2

The Hunt Read online

Page 2

“No, like, do I want to be a he or a she or what.”

“I’ll bite. What pronoun do you like?”

Ecky hesitates. “I . . . don’t know yet. I think she/her for now.”

“Okay. You let me know if it changes. Otherwise I’ll just call you Ecky.”

A moment of hesitation. “Actually, I’d prefer Joey.”

“Joey.” She thinks, Could go either way with that one: boy or girl. “Okay, Joey.”

“Thanks.”

“It’s cool. You’re good walking home, then?”

“Yeah.”

“See you on the flipside, Joey.”

“They call it ‘genderqueer,’” Shane says in the middle of driving.

“Huh?”

“What Joey is. I think they call it genderqueer. Or maybe genderfluid?” He frowns, suddenly—probably because Shane doesn’t like not knowing things. Little Shane Lafluco. Not a hair out of place. Nary a wrinkle in his plaid shirt. He’s taken lately to calling himself a nork—a nerd and a dork. He says it’s the “age of the nork,” with geek stuff suddenly becoming cool. She told him, good luck with that, you’ll still get your ass kicked if you run around school talking about Doctor Who instead of football or cow-tipping.

“I thought queer meant ‘gay.’”

“I dunno. I think it just means ‘strange.’ Or ‘to change something.’”

“Oh.”

He drives for a while, past the road that would take you up to Grainger Hill, to the trailers and rinky-dink ranchers where you can buy weed and meth and old lawn mowers and older washing machines. Atlanta can see on Shane’s face that he wants to say something. He doesn’t hide it well. He gets this look like he’s tasting something funny, or like maybe he’s gotta go to the bathroom. Even Whitey knows something’s up. From the back, the dog pokes his big-ass head between the seats and just stares at Shane, unblinking. Stern and stoic.

Finally she says, “Oh, just spit it out already.”

“Well—uh.”

“Say it. Lay it on me.” She pats her chest.

“Uhhh.” He visibly swallows. “What are you doing?”

“Like, right now?”

“Like, with all this. With what just happened back there.”

She squints an eye, raises one eyebrow above the other. “You know what I’m doing. You were with me when we made the video.” Before school started, she and Shane got together, made a YouTube thing about how no, it doesn’t get any better, you have to make it better. And one way you make it better is by calling Atlanta Burns. Helper of the downtrodden. Defender of the underdog. Friend to freaks, foe to bullies. “That was you, right?”

“It was me, yeah, duh, I know.” A flare of irritation in his voice. “It’s just, I didn’t know you were going to ask for money.”

She shrugs. “Nothing wrong with money.”

“No, yeah, it’s just—it cheapens it somehow.”

“Money does the opposite of cheapening something.”

“I guess I’d just rather you be doing this because you want to, not because it’s a job. When you get paid for it, it’s like . . . you’re some kind of mercenary.”

“Rather than what, a superhero, like in your comic books?”

“I guess.” He scrunches his face. “That sounds dumb, huh?”

“Well, uh, I dunno—” Oh, hell with it. “You know, yeah it does. Because the world isn’t like that. I’m not like that. There are no superheroes and I’m sure as shit not one of them. Okay? Jeez. I do want to help people, but at the same time I gotta get what’s mine, too. I provide a . . . service. And people pay for it. Same as anybody doing any job, even a job they believe in, a job they love.”

“Lawyers do pro bono work all the time.”

She snaps, “Well, I’m not a dang lawyer, am I? I’m just . . . me. Dumb Southern girl in the middle of Pennsylnowhere, carting around a one-shot scattergun and attended to by the Venezuelan Charlie Brown and a dog so big and so dumb that he doesn’t know a gunshot to the head should’ve killed him. I swear, he’s so stupid he’s probably dead and just hasn’t figured it out yet.” Whitey, for his part, pants and nuzzles her ears with his sloppy muzzle.

“I miss Chris,” Shane says suddenly. And it’s like a thunderclap—silent, but still felt deep inside her. A pit of grief. A sucking chest wound like a bullet straight through her lung.

“I know. I do, too.”

“I just want to make sure we’re honoring his memory.”

“Yeah.” She nods. “Yeah. Listen, no harm, no foul you don’t wanna do this anymore. Or if you want a cut of the money—”

“It’s okay. I’m good. I just—I dunno.” He gnaws on his lip. “What are you going to do with the money?”

To that, she just shrugs, like she doesn’t know the answer already. Like it’s not a key to a lock. Like it’s not a ticket to ride.

CHAPTER TWO

They drive past the barns and tractors and the bent-elbow sharp turn sign that the drunk in the pickup took out last month. They go past the fading corn and the Cat Lady’s house, past a rusted combine, past a pile of bones that used to be a deer. Shane drops her off at the foot of her driveway where she can grab the mail (bills, junk, junk, bills, someone else’s mail, bills). Then she huffs it down the driveway on foot, mail in one hand, shotgun in the other. Whitey trotting alongside—him snuffling and snorting as he slaloms between invisible tentpoles, like he’s got the scent of something and can’t shake it.

A low growl rises in the back of his throat.

Atlanta sees why.

There, parked by the house, a well-abused Crown Vic.

And sitting on the front porch: Detective Holger.

“Hello, Atlanta.”

Her guts tighten. “Hey, Detective Holger.”

“No need to be so formal. You can call me by my first name.”

“I don’t know it.”

“Cherry.”

A scowl. “Cherry? That sounds like a stripper name.”

“Well, in this case it’s a cop name. Cherry Holger.”

“Oh. Sure. I’m still gonna call you Detective Holger, though. I was taught to respect my elders.”

There—a moment of hesitation on the cop’s face before a slow smile breaks out. “I’m sure that’s true.” A hint of sarcasm, maybe. Atlanta thinks suddenly, This ain’t gonna be a friendly visit, is it?

Holger, she always looks like she’s hung on the line to air-dry—everything rumpled and wrinkled. No idea how old she is—once someone hits about forty, Atlanta kinda figures they’re a short hop, skip, and jump from the funeral home—but smart money says she looks older than she is.

Every time Holger shifts—a lean forward, a swipe of dirt off her denim—Whitey lowers his head and stares. Like he’s ready to make a move when necessary. Atlanta can’t blame him. Last time Whitey saw Holger, it was at the police station—just minutes before another cop, Petry, shot Whitey in the head.

Petry. The name crawls up inside her like a cockroach.

“You out shooting?” Holger asks.

“Oh. This?” She looks at the gun like, Oh, hey, who put this funny shotgun in my hand? “Just shootin’ cans.”

“You being safe?”

“I am.”

“You do any hunting?”

“Sure,” Atlanta answers. True, maybe, from a certain point of view. But she doesn’t like where this is going so she changes the subject: “Mama know you’re here?” Atlanta asks. “She should’ve gotten you something to drink. Sweet tea, some Crystal Light, glass of ice water maybe. Though our water’s been tasting funny, lately, I’ll be honest.”

“I’m good, thanks. Your mother’s at work.”

Atlanta’s laugh is husky and rough. “Work. That’s funny.” She offers her left leg. “Pull the other one and candy will come out.”

“Maybe you should talk to her more, because she has a job.”

Narrowed eyes. “Really?”

“Mm-hm. At the Karlton.” The little coffee-and

-bakery place by the Sawickis’ Polish food stand? Huh. “She’s been working there about a week.”

So that’s where Mama’s been going.

“Great. Good for her. How’d you know it?”

“I eat there.”

“Oh.”

“Take a seat.”

She scuffs her boot against the stones. “I’ll stand. I sit all day in school.”

“Can we talk?”

“Kinda what we’re doing right now.”

Holger laughs a little. “I like you, Atlanta. You’re tough. Most people who go through the kinds of things you’ve gone through, they don’t make it out okay, if at all.”

“I haven’t made it out yet.”

“And that’s what I’m worried about. You’ve spent some time at Emerald Lakes. And the thing with Ellis Wayman and the Farm, and then your friend, Chris—it’s a lot for an adult to handle, much less a girl like yourself.” A pause. A moment of calm before the lightning. “Then there’s the video.”

Yup. Here it comes.

“I don’t know what you mean,” she says, playing dumb.

“C’mon, Atlanta. I’ve seen it. Everyone in town has seen it. It’s on YouTube, for Chrissakes. And though nobody has made any official calls to the department about it, people talk. We know you’re . . . making good on your promises. Like the thing with Tim Schmidt?”

“Shitty Schmidtty.” Atlanta sucks a little air between her teeth. “Such a shame. Crapping his drawers in gym class? I mean, it’s right there in his name, you’d think he’d be more careful. Maybe he had a stomach bug.”

“Or maybe someone slipped laxatives into his school lunch.”

“I can’t imagine why anybody would do that.”

“Maybe because he was threatening a girl at your school. Do you know Dolores Kimpton?”

“Name’s familiar.” Familiar because Dolores—Dolly—hired Atlanta, not that she’d admit it here and now. Tim Schmidt, that weasel-dicked chode, was making all kinds of suggestive comments to Dolly about what he’d do to her if she didn’t go with him to Homecoming dance. He’s one of those types with bigger balls because he’s backed up by a crew of bros and buddies: the haw-haw types, a bully’s chorus, folks who give him power by laughing at his jokes and egging him on. But he fouled his gym shorts thanks to Atlanta—and, story goes, it got bad. Real bad. Ran down his leg, into his socks, and onto the gymnasium floor. Another kid, Gary Moynihan, stepped on it and slipped. Now nobody will talk to Tim. And now he’s Shitty Schmidtty all the way home.

“How about Alberto Willis?”

“That one I don’t know.”

A lie, because she does. Little Alberto. Twelve years old. Perpetually picked on by another kid at his bus stop, Colin Strauss. A richie-rich shit, same age. Alberto said nobody else would help him. At first she wasn’t sure how to deal with that one—because how do you intimidate a twelve-year-old like Colin Strauss? Turns out, twelve-year-olds get spooked lickety-quick. She told him, “You ever pick on Alberto again, I’ll kill your mother, your father, and your guinea pig.” She’d never do any of that, of course, but it’s so easy to lie to a twelve-year-old. You can tell them Bigfoot will show up on the back of the Loch Ness Monster with Slender Man riding shotgun, and they’ll buy in.

“What about Mitchell Erickson? John Elvis Baumgartner? Gordon Jones? Virgil Erlenbacher?” Those names. She knows. Something. Maybe not everything.

“Sure, I know some of them. Just from school.”

“Just from school.”

“I’m not real social. Kind of an introvert.”

Holger stands, changes the subject. “What are your plans, Atlanta?”

“Thinking of having some dinner. There’s a can of Campbell’s Chicken and Stars in our pantry that I’ve had my eye on for the better part of a week.”

Another step closer. “I mean . . . long-term. After school.”

“Guidance counselor and vice principal both asked me that same question today. Must be something in the water. Maybe that’s why it tastes funny.”

“You’re a senior now. It’s time to think about it.”

“I’ll tell you what I told them: I take it one day at a time.”

Holger steps close now. Whitey’s hackles are up—fur like the bristles of a brand-new toothbrush. Atlanta steadies him with a hand, and he eases.

“Listen,” Holger says, lowering her voice. “You have to look farther down the road. Find a future for yourself. High school’s short, much shorter than you think. Your best bet to make it out alive is to have a plan.”

“Sorry. Don’t know what to tell you.” That’s what she says. What she thinks is, I have a plan, Cherry, don’t you worry your frumpy head about it. But I’m not going to tell you what it is, because it’s not your dang business.

“I’ll see you later, Atlanta.”

“See you. Thanks for the talk.”

“Oh, one more thing,” Holger says, turning around just as she’s about to pop the Crown Vic’s door. “Officer Petry.”

That name again. Like an ice pick right in her middle. Atlanta tries not to flinch, but she’s not sure she managed.

“Him I remember. Hard not to, since he shot my dog.”

“He’s been missing for some time now.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.” Her words don’t match the sound that they make—much as she tries, Atlanta cannot inject sorry-feeling into that statement.

“We found his cruiser not far from here. Parked up the road. Nobody’s seen him.”

“Weird.”

“You haven’t seen him?”

“Mm-nope.”

“He didn’t come here?”

“Should he have?” Atlanta asks, knowing full well that he did come here. To kill her. And she shot him in the hand, sent him packing.

“I guess not. If you ever hear anything, let me know?”

Way she asks, it almost sounds like, I know something already. Maybe that’s paranoid. How would she know? In the past Atlanta figured Holger for one of the good ones. Maybe it’s time to reconsider that.

For now, she just says, “Sure thing,” and gives a little wave as Cherry Holger slides back into the car and heads down the driveway.

Upstairs in her room, Atlanta reaches under her bed, straining at the shoulder. Her fingers search the floor and push through junk: an old sweater, a CD case, a tangle of hangers, an opened bag of off-brand Doritos (Coolritos). All of it put there on purpose, debris in the way of what she’s trying to hide. What she’s hidden so well she can’t even find it herself.

Unless it’s not there.

Worry lances through her like a hot pin. No, no, no, c’mon, now—the hangers rattle, the bag of chips shakes, and then—

There it is. Her fingers feel the edge of the shoebox.

She slides it out. An old Florsheim shoe store box bound up with bungee cords. Atlanta undoes the cables, pops the lid, and looks inside. Couple stacks of bills now. Almost two grand in there. That money sits next to a little red notebook. She touches the notebook—not sure why, really, maybe just to make sure it’s still there. Then she throws Ecky’s money on top of the other money before quickly binding it up again.

Back under the bed it goes. Behind the debris and hidden from sight. The shotgun is the final piece; she slides it there, just near the edge. Ever in reach.

By the time Atlanta goes to bed, Mama Arlene still isn’t home. The Karlton closes at, what, seven on a weeknight? Mama may have a job, but it isn’t the end of her night. Something else is going on.

Atlanta lies there in the dark for a while. Thinking on it, on how her mama is hiding something. She has been acting skittish lately. Cheeky, like she’s got something she wants to say but can’t or won’t or doesn’t know how.

Her brain tosses it back and forth, over and over again. A hot potato bouncing around. She thinks about Ecky. And Shane. Her mind drifts to school and her future, because right now everyone seems to want to talk about that: what’s next, what do

you want to be when you grow up, hey, why don’t you go ahead and plan your next fifty years, gee gosh golly won’t that be a hoot. As always, her mind drifts back to the place it always drifts; she thinks about her friend, Chris, and how he won’t have any future at all. So why does it matter?

His voice finds her there in the dark sometimes, the sheets tangled up around her legs like slick seaweed trying to drag her down deeper underwater—his voice, always just a whisper: You could’ve saved me. Sometimes it’s You did this to me, or Why can’t you just quit picking scabs, Atlanta?

It doesn’t get better, and you can’t make it better.

So why even try?

Outside the room, a squeak of a floorboard.

Sweat laces the lines of her palm. Her mouth goes dry as a wad of cotton. Atlanta tells herself to just ignore it, even as her heart starts to beat so hard she can see the faint shape of the bedsheet over her chest bouncing like the front of a kick drum. A high-pitched whine in her ear. The smell of gunsmoke.

Another squeak. Footsteps. Something clicking (like the hammer of a gun).

Nobody’s there. She knows it. This happens every night. But it doesn’t matter because the idea seizes her just the same, grabbing her like a pair of big hands closing around her neck. Everything is tight—jaw, chest, throat, thighs.

A foolish thought hits her: I’m having a heart attack. Of course she’s not. She’s just a teenager. But maybe it’s a heart defect. Or maybe someone is really in the house. Or maybe her brain is just broken.

Faint footsteps.

Someone’s here. Here to hurt her. It’s not true, dangit, stop thinking about it, but then there’s a long creak—a foot falling on a floorboard, and that one seemed real, real as a brick thrown through a window, real as a gun heavy in the hand, and she thinks back to that story of the boy who cried wolf. What if, this one time, this isn’t just her brain crying foul? What if it’s not some cruel pairing of insomnia and a panic attack, and it’s real?

Whitey may not know it. He sleeps out in the garage, and that dog sleeps like (wait for it) he’s been shot in the head (rimshot), or worse—maybe he’s already been killed. Maybe whoever it is—Petry or one of Ellis Wayman’s people or some neo-Nazi bastard she hasn’t even met yet—killed Whitey already.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

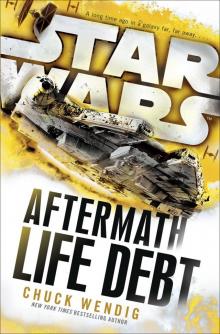

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt