- Home

- Chuck Wendig

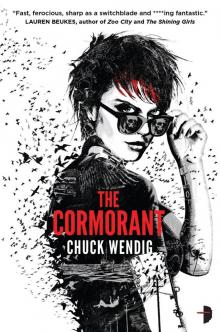

The Cormorant Page 6

The Cormorant Read online

Page 6

Miriam’s hands are shaking. “Speak sense, bird.”

“Are you going to see Mommy while you’re here?”

Miriam flings her keys at the big black scavenger.

The keyring rebounds off the sink, then the mirror, then lands in the well of a different sink. The bird is gone. One black feather remains, stuck to the grimy porcelain with a waxy bead of blood.

Miriam finishes peeing, rescues the keys, then hurries out.

ELEVEN

RINGY-RINGY

Outside in the parking lot Miriam gasses up the Red Rocket with the last of her cash, then parks off to the side, plants her butt on the hood, and smokes.

She lifts her ass off the car and plucks three pieces of paper – small, not quite fortune cookie fortune size, but close – from her back pocket.

Three phone numbers.

One: Louis. She hasn’t seen him in over a year. Hasn’t spoken to him, either – she ditched her last phone in the river when she got the hell out of town with old man Albert. Albert, who was supposed to take her south. All the way to Florida if she could manage it. To see her mother.

Which leads her to the next number.

Two: her mother. Back in Pennsylvania, during the Mockingbird murders, she decided – or perhaps was compelled – to visit the house where she grew up. Her mother’s house, or so she thought. Instead, that fuck-up Uncle Jack was living there. She found out her mother was living in Florida now, doing – what was it? Missionary work? And after all of it was done, after the Caldecotts were dead and Wren was saved, she really thought that she’d go to Florida, see her mother. But she always found a reason to point Albert in a new direction – train museum, amusement park, crayon factory, sex emporium. He knew she was avoiding something. But old Albert was good enough not to go picking scabs.

Albert’s dead now. He must be. That’s what the visions told her, and they haven’t been wrong yet. Dropped dead in the tall, misty woods. Looking at a picture of his wife. And loving her.

Him and Darnell, the car salesman. Men who died with love in their hearts. Is that even a thing she’s capable of? What does her heart contain? Vinegar and venom? Grave dirt and formaldehyde? Nicotine and dirty snow?

And she thinks, These two phone numbers are heavy. Pregnant with the potential for love, for connection, for reconnection, even resurrection – but here she worries that these relationships are already dead and buried, and if there’s one thing she knows all too well, it’s that once you’ve killed something it stays in the ground where you put it.

Still, she thinks, Call one of them.

Call Louis. Just to see how he’s doing.

Call her mother. To ask if they can see each other.

But then: that flare of anger. Louis doesn’t understand her. Her mother understood her even less. These are not my people, she thinks.

She shoves both those numbers back into her pocket.

Then she grabs the third number.

The man from the Craigslist ad.

She calls him. Tells him she’s here. In Florida.

He speaks slow. Not stupid-slow, just laid-back-slow. Peach Bellinis and sun-baked lounge-music slow. He asks her where she is. She tells him: Daytona. “Well, damn. Still got about a seven-hour trip till you get here.”

She asks him, “Where’s ‘here?’”

“Big Torch Key.”

She hears that gravel-and-grit in his voice, a Springsteen growl tempered by a Neil Diamond smarm. When he says Big Torch Key he sings it as much as he speaks it.

He tells her the address. Gives her directions.

“This isn’t about sex,” she says. “I’m not a hooker.”

“It’s all good,” he says, though she’s not sure that answer means anything at all.

Miriam tells him she’ll see him at eight.

He says he’s looking forward to it.

Then she hangs up her cheap-shit burner phone and stretches one last time before dropping her sore butt back into the Red Rocket.

The journey continues.

TWELVE

LIKE MOSES IN A RED FIERO

Driving through the Keys feels like threading a needle.

Ahead of her, a ribbon of asphalt: sun-bleached, sand-blasted, salt-brined. In some places, the ocean is ten feet to one side of the road, and ten feet to the other. To her right, Florida Bay, to her left, the Atlantic Ocean, and she’s carving a line right between them, a finger tracing the windowpane between two sheets of emerald glass.

Palm trees sway. Flocks of pelicans cross the bruise-dark sky like something prehistoric – a cabal of pterodactyls out of their time. Few beaches. Lots of boats. Old motels with their old motel signs: The Sandpiper. The Sunset Cove. The Coconut Cove. Smuggler’s Cove. The Lookout Lodge. The Drop Anchor Inn. The Pelican. The Pines. The Conch Out. Big tall signs out of the 1950s. Some gone dark, half-collapsed. Others dirty, half-wrecked, but still lit: red light painting vacancy, vacancy, vacancy in the deepening night.

Tiki bars and marinas. Ramshackle stands selling fish tacos and homes hidden behind the palms. Men and women walking in the coming dark with fishing rods and bait buckets. Powder blues. Coral pinks. Green trees. Smeary neon.

It’s a kind of dipshit, half-ass, hillbilly paradise – lazy and sunburned and swaying in the wind like the palms on both sides of the road.

This isn’t my place, she thinks.

Then again, what place is?

She drives down through Key Largo, through Tavernier, through Islamorada, through Marathon, threading the needle and stitching together tiny islands. It all feels poorly held together by the white bones of various causeways, like all it would take would be one hard wind blown from the puffed cheeks of a drunken god to scatter the islands to the corners of the map.

Speaking of the map: she looks at the one open on the passenger seat next to her, a map nested in the remains of snack food bags and energy drink cans and cigarette packets. Miriam realizes the Keys look like a fingernail bitten most of the way off – but still hanging there at the tip of Florida’s broken finger.

A hangnail, she thinks.

It’s all one big hangnail.

She feels that way sometimes. Like a hangnail that won’t come off.

And suddenly she wonders if the Keys are her kind of place.

She keeps driving. Down through the Middle Keys. Over the seven-mile bridge that rises like a hump over the water. Like she’s driving over a dead dinosaur’s bent back.

She fumbles for a drink in the cup holder–

Something stirs in the passenger seat.

A crow. Too big to be a crow. A raven. Black feathers wild and bristly like the mane of a tarred lion. Ink-dark beak clickity-clacking.

“Almost there,” the crow says in Louis’ voice. “Killer.”

It stoops its head and pecks bits of something spongy and gray off a purple handkerchief beneath its talons. Peck. Peck. Peck-peck.

She throws an empty Red Bull can at it.

The can rebounds off the inside of the passenger side door.

The bird is gone.

And ahead, a sign: Big Torch Key.

THIRTEEN

TORCH KEY

The Fiero drives under power lines. She follows the road that turns off toward the gulf side of Middle Torch Key and winds its way through a salt marsh of scrub and stunted palm. The air conditioning in the Fiero suddenly grumbles, vibrating like a paint-shaker, before giving off a cough and a burning smell.

She curses under her breath. Fiddles with the knobs. Slams the vents with the heel of her hand before finally rolling the windows down.

The humid air crawls in. A few cool breeze streamers come with it.

Bats dip and dart overhead. Shadows blacker than the night, flitting after mosquitoes.

Another bridge from Middle Torch Key to Big Torch Key.

Along the way she passes a shirtless man on a rickety bike. His skin glistens in the yellow of her headlights – red flesh like he’s a kielbasa left

too long on the grill. He turns toward her, toothless and drunk, and gives a sloppy wave that almost causes him to ditch the bike in a pothole.

She keeps driving.

Big Torch Key.

Nothing out here. She’s beginning to think this is some kind of joke. Even in the damp, slithering heat she can feel the skin on the back of her neck and arms prick up, the hairs standing at full attention. Worry tickles at her like a rat licking its paws. Out here it’s just road and scrub and mangrove, and it’s then she thinks, This is some kind of game. I drove all the way to Florida to fall prey to some sicko’s amusement.

Of course it’s a ruse. Five grand? Off of Craigslist? Shit. Shit! She thinks, I have to get the fuck out of here – fast, too, before she goes too far and drives over a spike-strip and blows her tires and ends up part of some twisted cannibal game out here in the subtropical nowhere–

But then she sees. Ahead, the flickering of actual torchlight.

Glinting off the metal of a driveway gate.

She sees a mailbox – a faded blue dolphin holding a mailbox, actually, some kind of roadside statue. Ridiculous and tacky, sure.

But also a sign of life.

She eases the car forward.

The number on the mailbox matches the number on her directions.

She’s here.

It’s real.

Well. OK, then.

As if on cue, the gate opens. Mechanized.

It shudders and squeals as it swings wide.

She eases the Fiero into the driveway. White gravel grinds beneath her tires. Ahead, past the half-circle drive, sits a plantation-style house. Bent palms stand on both sides of the house like hands sheltering it. Or perhaps propping it up.

Warm orange light from within. Tiki torches lining the drive, flame licking the air, little vines of white smoke climbing.

The front door opens. A man comes out. Older. Late forties. Early fifties. Hair the color of sand swept down over his ears: long, shaggy, wind-frizzled. His arms are out wide, welcoming. Big smile. White teeth.

He beckons for her to park by the side.

She kills the engine. She gets out, takes the sunglasses off the top of her head, tosses them on the dash.

The man’s already on her. Coming toward her fast, arms up and out–

She’s already ready for it.

Her wrist flicks and the black four-inch lock-blade from her back pocket opens.

She points it, thrusts it at the open air. Swish, swish.

“Whoa, whoa, darling, what the–” He laughs, nervous, taking a couple clumsy steps backward. “I’m not here to hurt you.”

“Then maybe don’t come up on a girl so fast.”

“It’s not like that–”

“I don’t know what it’s like. You invite me out here. Middle of the night. Middle of nowhere. Promise me five grand. Then come up on me like a hungry dog sniffing for treats? That’s a good way to get shanked, Jimmy Buffett.”

He laughs. Still nervous. “Well. I sure don’t want to get shanked.”

“Then take five more steps backward.”

He does.

“What’s your name?” she asks.

“Steve.”

“Steve what?”

“Steve Max.”

“That’s two first names.”

“I guess it is, yeah.”

She keeps the knife pointed at him. A stabby accuser. “My name’s Miriam Black.”

“Hi, Miriam. I’m glad you came down to meet me.”

“Go,” she says. “Go inside. I’ll follow you.”

“Are you going to rob me?” he asks.

“Are you going to rape me and kill me?” she asks him. “Or kill me and rape my dead body?”

“That wasn’t my plan.”

“And robbing you wasn’t mine. Like I said, go. I’ll follow.”

He smiles. Nervous. Then does as she asks.

Her gaze flits through the scrub and the trees. Looking for shadows. Nothing. Still, something here feels wrong. Paranoia crawls over her like a colony of ants.

With a deep breath, knife in hand, Miriam goes inside.

FOURTEEN

HEMINGWAY’S SPIRIT

The inside of the house is full of dark timber and tan bamboo. Palm fronds. Tiki mugs on shelves. A big-screen TV on the far wall – big enough you could turn it on its back and use the thing as a dining room table for six people. A ceiling fan of thatched wood turns lazily overhead.

Steve precedes her, and once he’s inside, it’s like he stops worrying about the crazy road-weary chick with the knife in her hand. Like he just lets go of all his cares, letting them float to the heavens on the wings of pretty-pretty butterflies. He saunters over to a one-person bar in the corner, steps behind it, his shirt open, his hand scratching the salty wire-brush hairs growing up out of his bare chest. He’s so tan Miriam thinks someone should skin him and use his pelt to make a nice set of luggage.

He reaches down under the bar and she barks – “Hey, hey, hey!” – and he quickly jerks back up again, hands up like he’s a bank teller about to get robbed. He laughs, nervous.

“Ho now, what’s the problem?”

“What’s behind the bar?” She waggles the knife at him.

“Rum.”

“Rum?”

“I was gonna make us a couple of daiquiris.” He pats a stumpy bar-top blender. “Kind of a welcome to the Keys drink. Hemingway’s favorite cocktail.”

“Hemingway was a diabetic. His favorite drink was a dry martini.”

“Oh. No shit? I didn’t know that. You read a lot?”

“When I can.” Homeless girls love libraries, she thinks but does not say.

“I have some vodka and vermouth here.”

“That’s not a martini.”

“Why, sure it is.”

“Jesus, dude, I don’t want to get into a cocktail pissing match with you, but a martini is gin. Always gin. Putting vodka in a martini is like–”

“Whiskey in a margarita?”

“It’s like spitting in my mouth and calling it champagne.”

His mouth seems frozen in a rigor mortis smile. “I don’t have gin.”

“Then I don’t want whatever it is you would call a martini.”

“Back to daiquiris, then.”

“Are you going to poison me?”

He crosses his arms and leans forward on the bar. Ringlets of beach-blond hair frame his face. “Miriam, I understand your apprehension, I do, but this isn’t anything… weird. I’m cool. We’re cool. Here’s how we’re gonna fix this, OK? Over there on the side table by the patio door, there’s a canvas bag, and in that canvas bag is twenty-five hundred bucks. Half of what I said I’d pay you for the vision. You go over there. You take that money. You can leave if you want to. But if you stay, I got a grill out on the patio and a table out on the dock and we can sit out there and eat some shrimp and mahi I got cooking up – little lime, little cilantro, little mango salsa – and then we can get down to business. By which I mean you tell me how I’m going to die and you get the other half of your money and then you can go on your way with a full belly and a fat sack of cash.”

“Why?”

“What?”

“Why do you want to know how you’re going to die?”

His easygoing smile falls away like dead leaves off an autumn tree. He searches for words. It’s like he doesn’t even know the answer to that question, which is eventually exactly what he says. “I don’t know. I’ve always been a little obsessed with it. Living life to the… well, to the max. It is my last name and all, so I figure I better live up to it.” Here an awkward laugh like he’s knows it’s super-douchey and not very funny but it’s out there and now they have to deal with it. “I just want to know how much time I got left. I’m on the wrong side of middle age and you’ll see – one day you’ll get older and realize that the ride starts to speed up when you think it should be slowing down.”

She lets the knife fall to her side a

nd hang there in her hand.

Miriam goes to the white canvas bag. Hooks a finger around a strap. Lifts. Separates. Sees wads of cash piled haphazardly atop one another, held together with little rubber bands.

“You can count it,” he says.

“I’m good. It’s good.”

“You wanna eat?”

She closes the knife and pockets it.

“I could eat,” she says, then walks past him out onto the patio.

FIFTEEN

DISEASEBURGER IN PARADISE

Outside: the heady, narcotic smell of shrimp and planked fish on a small charcoal grill. Steve goes on a hunt for plates, doesn’t seem to know where he keeps them. He tells her he has a new maid – “Cuban girl, skin like café con leche, just pretty as the sunset, but she always rearranges my stuff and it’s like a scavenger hunt trying to figure out where.”

Miriam sits at the patio table. A dock extends out over the bay water like a red carpet to the deep blue oblivion.

The moon hangs fat in the sky like it might give birth to a litter of baby moons, and maybe some stars, and a swirl of galaxies, too.

Something bites her arm. A mosquito, she assumes, though she can’t see it in the torchlight.

She swats at it as Steve puts a plate in front of her. Alongside, a drink. A pink drink. She scowls at it. “Strawberry daiquiri,” he says, obviously obsessed with the damn things, and she sniffs at it and pushes it away – too cloying, too strawberry, too pink. She’s thinking of just asking for the bottle of rum when something bites her arm again. Twice. Then a third time.

“Ow, sonofab–” Swat swat swat. She pulls her hand back and expects to see little greasy skeeter-stains, but no such luck.

“No-see-ums.”

“No-who-nows?”

“Little gnats. Fast little stinkers. Zip in, take a bite, then they take off again with your blood still in their mouths. Here.” He takes a long-neck lighter and lights a citronella candle. The chemical citrus stink fills the air. Whatever appetite she had is suddenly gone – her guts are already cinched up in stubborn knots and she’s not sure why.

She pushes the plate away.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt