- Home

- Chuck Wendig

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Page 6

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Read online

Page 6

Corollary: "Everything Is Dialogue"

Part of why dialogue reads so easy is because it's conversational, and conversation is how we interact with other humans and, in our heads, with the world. We talk to inanimate objects, for fuck's sake. (What, you've never yelled at a stubborn jar of jelly? SHUT UP HAVE TOO.) There's a secret, here, and that is to treat all your writing like it's dialogue. Write things conversationally. Like you're talking to the audience. Like you and the audience? Real BFFs. You can abuse this, of course, but the point is that in conversation you'll use straightforward, uncomplicated language to convey your point -- no value in being stodgy and academic when you're just talking. So too is it with writing, whether it's description in a screenplay or in fiction, you'll find value in straightforward, uncomplicated, even talky language. Talk with the audience, don't lecture at them. Everything is dialogue. Some of it's just one-sided, is all.

25 Things You Should Know About… Description

1. Description Is A Misleading Term

Consider: if I were to say to you, "describe for me this lamp," you would begin listing off its traits in earnest. "Base made of iron-wood, 60 watt light-bulb, fraying electric cord, lampshade made of human skin," and on and on. But that is not what you do in fiction. I don't want you to describe every detail. I don't seek an accounting of all the brass tacks. First lesson is: don't describe everything. Knowing how to write description is often about know what not to describe.

2. Bowling A Spare

Less isn't exactly more, here -- less is less, but that's the side on which you should err. Better to make the reader hunger for more detail than be bludgeoned about the head and neck with it. A reader who wants to know more keeps reading. A reader who knows too much will put that book or script down and have a nap as if he just ate a whole plate of carnival food. (Sidenote: I’d shank a dude in the kidneys for a bite of funnel cake.)

3. The Reader Came Here To Work

The reader doesn't realize this, but he wants to get his hands dirty. Or, his brain-hands, at least. I'm paraphrasing the brilliant Rob Donoghue here, but it's like this: when Betty Crocker first starting selling mixes, they were super-easy to make. Packet of powder, add water, bake. But they didn't sell -- in part because they were too easy. It felt like a cheat. So, Crocker chose to leave out the egg -- meaning, a housewife had to add an egg, an extra step. And bam! They sold like a sonofabitch. The lesson is that, your audience wants to work. When they work, they feel invested. Hand them a pick-ax, a pith helmet, and a backpack sprayer filled with sex-lube. Don't give them all parts of the description -- let them fill in details with their imagination. Let them add the egg.

4. Your Bloated Ego Makes For Swollen Description

The author likes to be in control. And you are. But you have to cede some intellectual and imaginary control to the audience. You don't need strict autocracy over description. You only need agency over those details that are critical for the story to be what you want the story to be. Leave everything else to the reader to invent inside their crazy head-caves.

5. Zelazny's Rule Of Three

This reportedly goes back to Roger Zelazny, who said you should stop at three details in description. People aren't going to remember much more than that, anyway. It's a good rule, though I don't think you need to be quite this mathematical about it. Rather, like with most writing advice, the tenet and the practice of that tenet are a bit divergent. (After all, does he mean three details about one character? All characters? The room? A lamp? The heating vent? If I'm allowed three details per item in the room, then suddenly I'm writing 1,436 details. I think it just means, “keep the details to a minimum, asshole.”)

6. Describe What Matters

Describe only what matters to the story. If the reader must know something, then ensure she knows it. I don't give a fuck about your lamp. Or what leaf-rot is on the oak tree outside. Or what the tag on the dog's collar looks like. If you choose to describe these things, it should be because I need to know them. A character is going to brain another with the lamp. The leaf-rot is part of a larger plot point about some sort of botanical doom-fungus. The tag on the dog's collar is shaped like a lucky four-leaf clover because his owner is William "Irish Billy" McArdle, an ex-IRA bomber turned merc thug, and the clover is his signature.

7. Speedbumps And Slammed Doors

Over-description slows down the pace of reading -- and, if it's truly too egregious, the reader will slam the door and walk away. (In Internet parlance? tl;dr -- "too long, didn't read.") This is true when writing scripts, too -- description separates out action and dialogue, and those two things keep a script's story moving. Heavy description can kill a script like a hammer-blow to the skull.

8. That's Not To Say Fat Is Not An Essential Flavor

That's not to say a reader won't find detail compelling. Fat can be flavorful. Simply describing the antagonist's Dodge Charger as "cherry red" seems like a non-essential detail. But always look for the ways that description can do double-duty. The fact that the muscle car is cherry red suggests deeper meaning. We know that red cars are likely to be pulled over. We intuit that red is a color of anger, blood, fire. The character's choice of color can tell us something about that character. Thus, the detail seems fatty, and it is -- but it's also an essential fat. Like what you get from olive oil, or avocados, or the unctuous barnacles scraped from the thighs of Oprah Winfrey.

9. That Goes For The Goddamn Weather, Too

Fuck weather. Too many writers go straight to describing the weather. I think it comes from that old saw, "It was a dark and stormy night," except everyone seems to forget that it comes from a laughably bad book. Describe the weather only if it matters. If a storm has physical effects on the plot, describe it. A miserably cold day might cause a car accident (ice) or lost visibility (blizzard). If the weather matters, tell us. Pro-tip: it usually doesn't matter.

10. Well, Somebody's A Moody Bitch

You can use description to create or enhance mood, sure. That is, I think, why some writers try to describe the weather -- "Oh! It's thundering, and so I'm creating a mood of impending doom." Really? You can't do any better? It’s thunder or nothing? Here's the thing: you can describe something in a way that is both meaningful to the story and conveys mood. Were you interested in stirring up a pervasive mood of rot and decay, you could describe the rust on the character's gun, or some skin disorder he's suffering. Those things can affect the plot (the gun eventually jams, the skin disorder worsens). Description there serves both mood and story.

11. Time To Take A Test

Walk into a room. Preferably one with which you're not intimately familiar. Look around for 30 seconds. Time that shit. Don't wing it. Then walk out. Wait five minutes. Make some toast. Pour a drink. Pet the dog. Masturbate wantonly. After five minutes, write down those details you believe are essential to capturing the "roomness" of that room. Write down as many details as you'd like. By the end, cut it down to three. Then cut it down to one. Just to see. How’d you do? You failed. F+. I’m kidding. I could never fail you. Not as long as you keep sending me checks.

12. Don't Bury The Lede

Stories often rely on critical details that come out through description. A facial tic. A bomb under the table. A mysterious artifact known as the "Astronaut's Anal Beads." But some writers bury critical details in a mushy glop of description. Don't bury the things the audience needs to know. Highlight them. Make them stand out. I don't want to get to page 156 and say, "Whoa whoa whoa, the antagonist only has one hand? Shouldn't I have known that?" and then it turns out that yes, you told me back on page 32, but you told me in the middle of a generally descriptive paragraph. Blah blah blah, red hair, nice shoes, one hand, big belt buckle, fat thumbs, blah blah blah.

13. Here's The Truth: I Might Just Skip That Descriptive Shit You Wrote

My eyes catch onto dialogue like a hangnail on a fuzzy sweater. My eyes slide over big patches of description like a fat guy going down a log flume greased with bacon

fat. Description is like sex with someone unpleasant: get in, get the job done, get out. We call that a "combat landing."

14. Break Description Apart With Your Word-Hammer

No, “word-hammer” is not a euphemism for your penis. My penis, yes. Your penis, no. What I’m saying is, shatter descriptive passages like toffee -- break it into pieces. Incorporate it into dialogue and action. Description doesn't need to exist as if time stands still so the protagonist can "take it all in." He can be running, talking, scheming, hiding -- the details he notices are the details he has to notice, and thus, are the details the reader must notice, too.

15. Pricking The Reader's Oculus With This Grim And Gleaming Lancet

Purple prose is the act of gussying up your words so that they sound more poetic. (Of course, that misunderstands poetry as some flowery, haughty thing.) If you dress up your language in such frills and frippery, you stand in the way of your own story. You do nothing but sound haughty, ludicrous, or some combination of the two. And yes, I said "frippery." If that's too purple for you, then pretend I said, "If you dress your language up in a bedazzled prom gown and give it a gaudy spray-tan..." Put differently: use the words that live inside your head. And if the words that live inside your head are those of an sentimental Victorian troubadour, then please close your head in a door jamb until you kill all that overwrought prose in an act of brain damage.

16. "The Thing Is Blue, The Dog Is Making Sound"

If you need to take the time to describe something, then aim for specifics. You can't just tell me it was a dog. I don't know what to do with that. Big dog? Little dog? Mutt? Pit bull? Rat terrier? Big-balled bulldog? Just telling me what the thing is goes a long way toward helping me place that object, character, or situation into the context of the story you're telling. Was she a leggy blonde? Was he a dumpy child? Description doesn't need to be long or drawn out to matter. It just needs to be specific.

17. Metaphor Is The Tendon Connecting Muscle To Bone

See what I did there? I used metaphor to describe metaphor. That's how a writer does things. That's some hard-ass penmonkey trickery, son. What? What? You gonna step? You gonna front all up in my face-grill? Ahem. Sorry. Where was I? Right. Metaphor takes a mundane part of the story and connects it to the larger experience of the audience. It says, "this little thing is like this bigger thing, this other thing." Metaphor is less about fact and more about feel.

18. Metaphors Are Always Wrong

They're not wrong to use. But like I said, metaphors aren't about fact. They provide inaccurate information, but offer instead keen artistic and figurative data. When I say, "On our sales team, Bob's the last sled dog in the line -- always got a butthole view of the world," nobody really expects that Bob is a dog, or that during a sales conference he's staring down the poop-chute of a snow-covered Malamute. Metaphors have power because they're wildly inaccurate, because they take two very unlike things and bring them together in the reader's mind.

19. And Yet Metaphors Must Find Essential Truth

A metaphor has to make some motherfucking sense. "Man, working night-shift is a real can of ear-wax, isn't it?" What? What does that mean? That doesn't mean anything. Maybe you mean something, maybe you have some keen understanding of night work and... cans... of ear-wax (can you buy ear-wax in cans?), but the reader doesn't grok your lingo. That's why a metaphor bridges a part of the story with the reader experience, not with your experience as an author. Everybody needs to get the metaphor. The Thing That Is Like Another Thing must share an essential truth. That's the connective tissue.

20. Everything Cannot Be Metaphor

Metaphors allow description to transcend a mere accounting, but even still, sometimes I just want to know if the girl has long legs or if the gun is loaded. Not everything needs to be a metaphor.

21. Clichés Are A Brick Wall You Make The Reader Crash Into

Using clichés makes Description Jesus turn water not into wine, but into starving ferrets that crawl up inside your bowels and eat your body from the inside out. "He ran like the wind?" Yeah, well, I kicked your nuts like a soccer ball. You're a writer. It's your job to avoid clichés, not run into them with your head.

22. Tell Me What The Donkey Smells Like

You don't need to rely on visuals. Many writers do. So you shouldn't. You have four other senses and so do your characters, so use them. Actually, there's a sixth sense, too: common sense. Common sense says you shouldn't overdo the "other senses" thing, and further, should only do so when it's appropriate. You might see or smell a donkey, but you don't taste it. Or you might touch it. Mmm. Yeah. Yeah, baby. Touch the donkey. Go on. Do it. What? Ohh. Uhh. Nothing. Please don’t call the police.

23. The Hardest Description Is When You Invent Stuff Out Of Thin Air

Creating a new monster out of nothing? Inventing some wretched clockwork gewgaw whose flywheel mechanism could destroy the world? Unfolding a whole new fantasy realm or planetary scape? This is when it becomes tempting to hunker down and describe the unholy shit out of stuff. Resist this temptation. I know. You're thinking, "But how will the audience know what I'm talking about? This creature, the Dreaded Horvasham Gorblim, has never before existed. The audience won't know that his horns are studded with thorns, or that his nipples look like crispy pepperoni. I have to build this monster for them. On the page. Inside their head." No, seriously, resist the urge. By not going much further than "thorny horns and crispy pepperoni nipples," you've already created an image in your head of the beast. So too have you pictured the wretched clockwork flywheel gewgaw. Like I said: the audience is willing to work. They will carry your water.

24. Novelists, Read Screenplays (And Screenwriters, Read Novels)

Novelists could learn a thing or two from the brevity of description found in screenplays. Therein you will find short collapsed descriptive nuggets that still manage to paint the picture and get the story moving. Further, screenwriters could learn a thing or two from novelists. Remember, screenwriters: your script needs to be readable before it needs to be filmable. It lives in the reader's head before it ever makes it to screen. Description must feel alive.

25. Like With All Things: Everything In Moderation

That's an old Greek idea, right? "Everything in moderation?" Of course, those guys were all huffing Zeus juice and banging pegasuses. Pegasi? Fuck, I don't know. Point is, description is a powerful tool in your narrative kit because, as it turns out, readers like you to help set the stage inside the theater of their minds. You can underdo it. You can overdo it. You need to walk the line, look at the shape of your page. Sentences or small paragraphs punctuated by stretches of dialogue and/or action is certainly a good shape for which to strive. Find the middle path and you shall appease the reader.

25 Things You Should Know About… Editing, Revising, And Rewriting

1. Forging The Sword

The first draft is basically just you flailing around and throwing up. All subsequent drafts are you taking that throw-up and molding it into shape. Except, ew, that's gross. Hm. Okay. Let's pretend you're the Greek God Hephaestus, then. You throw up a lump of hot iron, and that's your first draft. The rewrites are when you forge that regurgitated iron into a sword that will slay your enemies. Did Hephaestus puke up metal? He probably did. Greek myths are weird.

2. Sometimes, To Fix Something, You Have To Break It More

Pipe breaks. Water damage. Carpet, pad, floor, ceiling on the other side, furniture. You can't fix that with duct tape and good wishes. Can't just repair the pipe. You have to get in there. Tear shit out. Demolish. Obliterate. Replace. Your story is like that. Sometimes you find something that's broken through and through: a cancer. And a cancer needs to be cut out. New flesh grown over excised tissue.

3. It's Cruel To Be Kind

You will do more damage to you work by being merciful. Go in cold. Emotionless. Scissors in one hand, silenced pistol in the other. The manuscript is not human. You are free to torture it wantonly until it yields what you requir

e. You'd be amazed at how satisfying it is when you break a manuscript and force it to kneel.

4. The Aspiration Of Reinvention

I'm not saying this needs to be the case, and it sounds horrible now, but just wait: if your final draft looks nothing like your first draft, for some bizarre-o fucking reason you feel really accomplished. It's the same way I look at myself now and I'm all like, "Hey, awesome, I'm not a baby anymore." I mean, except for the diaper. What? It's convenient. Don't judge me, Internet. Even though that's all you know. *sob*

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

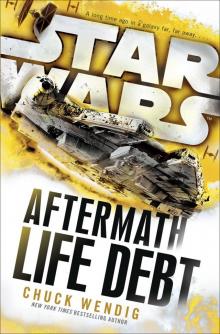

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt