- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Page 5

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Read online

Page 5

The fight has left her. Norra pushes her away.

“I’m not sorry,” Norra says.

“Of course you’re not.”

“I’m sorry you got dragged into it.”

Jas sighs. “Save your half-hearted sorry for when I’m dead in the hot sand.”

Norra’s voice breaks as she says: “Liberation Day. My husband. I fought Sloane and…I have to do this.”

“Fine,” Jas says. “So let’s do this. Where do we start?”

“You’re hurt.” She reaches for her friend, and after a gentle touch her fingers come away with blood. “The fall—”

“I’m fine.”

“The pod has a kit. A medkit. I can—”

Jas pulls away. She says more sternly, and in her voice is the admonishment of a child to a parent, the way Temmin would say it: “I’m fine.”

Norra’s mind goes to Temmin. I hope he made it out okay…that thought chased by another: I’ve gone and abandoned him again, haven’t I?

Norra cranes her head back. Up there, in the broad blue, she sees the faint shapes of the Star Destroyers hanging in orbit. Diaphanous, almost as if they’re not really there. Hallucinations. Or a vengeful ghost fleet, come to wreak their revenge.

“Looks like we found the Empire,” Jas says, licking blood from her lip and scowling at the taste.

“But why? Why here?”

“That, I don’t know. Hiding, maybe. We’re pretty far from anything anyone would consider civilization. Far from any trading routes. Far from the known worlds. Close to the edge of the Unknown Regions. Maybe they’re here, licking their wounds, hoping the NR won’t notice.”

“They’ll notice now.” If Temmin made it away, that is…

“What’s the plan, Commander?” Jas throws her hands up. “I ask again, where do we start?”

“What?”

“You came down intending to be all by your lonesome, but now you have me. You’re in charge of this little expedition. Do you have a plan?”

Norra sighs. All the anger she felt, all the panic—the noise has dulled now to a dim susurrus, and mostly she just wants to crawl back inside the pod and go to sleep. For days. For weeks. For all of forever.

“I don’t have a plan,” she confesses.

“Let me guess: no time to make one up?”

Norra barks a grim laugh. “Yeah. Well. I reckon the Empire will be looking for us before too long. TIE patrols, probably.” Norra rubs her eyes with the heels of her hands. “We collect our gear. Then we walk.”

“Any particular direction?”

“Just spin around, point your finger, and away we go.”

“You got it, boss.”

Here on the slopes of Mount Arayakyak, the Cultivating Talon, the jungles once served as a rain-forest orchard, providing the Wookiees with an array of fruits, the shi-shok being most prized because its utility was wide—the pulpy fruit was delicious and vital, the hull was hard enough to withstand nearly any impact, and the vines of the tree made for the strongest binding and climbing ropes known.

But the child that lopes through the jungle now does not know these things. He does not know the world’s history, for he barely even knows his own. He does not know that this rain forest was once lush and once gave his people life. All he knows now is that it is a scarred, carved-up place. Many trees are broken and collapsed against one another like campfire kindling. Others are sickened from the roots up—a poisonous black mold has taken them, rotting them, turning their fruits into hard, shriveled pods.

Lumpawaroo knows very few things. He knows his name. He knows that his mother was taken from him. He knows that his father has long been gone. He knows that he has been a slave for the rrraugrah—the hairless Imperial intruders—most of his life. But he also knows that recently, something has changed.

The bad song has ended. Each of the Wookiees had a song in their head, a song of fire and terror, a song like the sound of the thrumming wings from a swarm of drriw-tcha blood-worm flies. The song made them do things. The song screamed louder whenever they defied the milk-skins. At its loudest, the song could kill them—Waroo remembers when one of his slave-mates tried to scale the walls of the daubcrete bunker, and the song in her head caused her such misery that her neck craned back far enough to snap.

But now the song is gone.

The rrraugrah locked them away. They brought out the old chains and collars. They now force the Wookiees to work again with shock-lance and blaster, with screams of rage and baleful threat. Things have gotten worse since the song died. But in that, they have also gotten better.

Many of the intruders at this settlement have fled. Others have doubled down, gone mad, locked themselves away. Sometimes the milk-skins are there behind their doors, yelling, smashing things, weeping. They’ve ceased cleaning themselves. They hide. They even attack one another, at times. All while claiming to wait for something, someone, anyone to come. They think they will be saved. That someone will come to bolster their forces, to bring them new food, to help return the song to the Wookiees’ heads to control them once more.

Waroo feared that might be true, that someone might come, that the song might again be sung. So Waroo watched. And waited.

And soon the opportunity came.

One of the rrraugrah in a filthy gray officer’s uniform began closing the pylon-gate. This was Commandant Dessard, a vicious little man with a greasy peak of dark hair. Waroo waited until Dessard had almost closed the gate…

Then he leapt for the opening. Though Waroo was weak and starving, he summoned everything he could to make it through that gap.

And make it, he did. Once out, he kicked backward with both legs, knocking Dessard through the gap. Waroo shouldered the gate closed, then howled to the other young slaves—for this is a child camp, where the young Wookiees are prized for their small hands and their ability to climb oh so high—that he would come back to free them all.

Then Waroo fled into the jungle, down the slopes of Arayakyak, the Cultivating Talon, through the broken trees, up into their diseased boughs, across old rotten bridges, and through shattered homes hanging from cratered bark. For a time, he was alone. Now, though, that too has changed.

Waroo is being hunted.

The stink of Dessard is carried on the wind: sweat and waste and his own hatred. Waroo knows now why the man comes for him: The loss of one Wookiee is of no consequence except to the man’s own ego. He is angry to have lost one, to have been tricked and injured. That anger is a foul odor all its own, and Waroo can smell it. Worse, Dessard is not alone.

But Waroo is Wookiee. He is smart even though he is weak. He knows they cannot come for him up high, so he finds one of the diseased shi-shok trees, and Waroo ascends. He clambers from branch to branch, up a blackened vine that twists in on itself, through the sickened pleach. But his hand falls on something—a bulging fungal sac, one of the spore-pods that have helped to sicken the rain forest here. It erupts. From it comes a cloud of black spore, and Waroo inadvertently takes a deep sniff of it—

Everything goes white. He coughs, whimpering and bleating. Dizziness assails him; it feels like he’s spinning around and around, and his hands go slack and the world rushes up past him—

Waroo falls. He hits branches. Rot-curled leaves whip past him in a whirlwind. He bounces off a bough, and before he knows it—

Wham. The air escapes his chest in a cannon blast. He curls onto his side and tries to cough more, but Waroo cannot find the breath. He wheezes and whimpers. Just as his breath returns to him, so does the smell.

The stink of Dessard covers him like a tide of mud.

Dessard stands there, leering. His mouth is a vicious sneer. He has a blaster in his hand—a grungy, rust-rimed pistol. “You,” he hisses. “You thought you could get away. No one gets away. No one escapes. Not you. Not my own troops. Any who flee die. And they die very badly.”

Other Imperials encroach, forming a half circle behind the commandant. Waroo tries to get himself up

right, but his strength is sapped. The spore, the fall, the fact he’s already starving and weak…

But one thing that remains strong is his senses.

Waroo smells Dessard, yes. He smells the man’s sweat. He smells the Imperial’s willingness—no, his eagerness—to kill.

Then another scent.

A Wookiee scent.

A scent oddly familiar, one that stirs within Waroo a sudden lift of his blood and spirits—

Dessard makes a sound—grrk!—and is yanked backward through the scrub and brush. Branches crackle as he’s whipped away. Then the air goes bright with blasterfire. The other milk-skins are too slow. They’re cut apart. One is knocked back through the air so hard, his feet whip above his head before he’s slammed into the trunk of the shi-shok. Dessard comes back, crawling on hands and knees toward Waroo, his face a simpering mask.

A shadow descends upon him.

And with it, a scent that says, Father.

A tall, shaggy Wookiee with a bandolier steps over the commandant and plants a tree-trunk leg down on Dessard’s back, mashing him against the ground and into the mud. Others emerge from the brush: a gray Wookiee with one arm, another with a visor over one eye, and several milk-skins in raggedy forest-green camo, a firebird sigil on their arms. These others secure Dessard’s arms behind his back, wrenching them into a pair of looped cuffs.

The bandolier Wookiee sees Waroo and cocks his head. He utters a soft purr before the strength seems to go out of his legs. Waroo knows him. This is his father. This is Chewbacca. They crash together, arms around each other, the child’s head buried in the father’s chest.

Chewbacca lifts his head to the sky and ululates a good song, a true song, a song of family, of lost love found once more.

While senators argue in her office, Chancellor Mon Mothma tries very hard to make a fist with her left hand. The hand rests on her knee under her desk, and she focuses on the act of pulling her fingers into the center of her palm. She can’t do it, not yet, not quite. The fist she makes is less a fist and more a soft claw. Simply closing that hand feels like she’s trying to move mountains, requiring an epic effort that she dearly hopes is not being shown on her face.

“Are you listening?”

She doesn’t even know who asked the question. Oops, she thinks.

Looking up, she sees it’s Senator Ashmin Ek from the Anthan Spire. His lips are twisted up in a sour knot. His silver hair is in a sharp, ostentatious peak above his head. Ek does not like being ignored. He says as much: “Chancellor, I get the feeling you’re not entirely with us here today. You may see yourself as special, but I have taken precious time out of my schedule and put many meetings on hold for this committee…”

Some of the other senators gathered nod along with him: Bushar, Lorrin, and Rethalow. Next to them stands Jebel of Uyter—Minister of Finance for the New Republic. He does not nod, but he strokes his beard and hmms and ahhs, continuing to serve as the pinnacle of ineffective neutrality. (Nower Jebel is always at his most comfortable when he is firmly in the middle—never extending himself, not even by a toe or a finger, toward one side or the other.) Others look embarrassed by Ek’s outburst: Senator Oko-Po and Councilor Sondiv Sella in particular look on with disbelief.

“I apologize,” Mon says, humbly. “I am feeling a little distracted today.” And why ever would that be? she asks herself. Could it be because this is the last week that the Senate will meet on Chandrila? Perhaps because of the rise of the New Separatist Union, or the Confederacy of Corporate Systems, or the pirates and their so-called Sovereign Latitudes? Maybe that horrid Senator Wartol has gotten under my skin. Or maybe, just maybe, it’s because my left arm and the hand at the end of it barely operate as they should, thanks to the Empire’s attack on Liberation Day. “I fear it is best to end this meeting early and push it on to next month, once the Senate and my office have been moved to Nakadia. Will that do?”

“It will not,” Ek seethes. “The Committee for Imperial Reallocation is vital for distributing the resources of the fallen Empire—”

“It hasn’t fallen yet,” objects the broad-shouldered Sondiv Sella. He puffs out his chest as he talks—indicating that he’s harboring some anger. “We have to be careful not to think we’ve seen the last of the Galactic Empire. It has a long and deep shadow.”

“They have been beaten.” Ek sniffs haughtily as he says it.

“Coruscant is still occupied.”

“Coruscant is irrelevant! The Empire there is a shadow. They’ve no fleet. They’ve no weapons manufacturers or starship builders. Their bank has been plundered and those credits are now New Republic credits, which means they are ours to allot. The Senate elected me as head of this committee, so it is our time to do our job and not be held at arm’s length by a distracted chancellor. My home, the Spire, is in need of funds direly—”

It’s the Ithorian senator’s turn to scoff. Oko-Po turns her big bright eyes toward Ek and shakes her bent, stooped head. Through the translation device around her neck, she says: “The Spire is a wealth factory. You’re rolling in credits, Ek.”

“The illusion of wealth!” Ek says, erupting. “We are trying to demonstrate and project financial strength, but I assure you we are weakened by the disruption this war has wreaked on the galaxy. And I’ll remind you that just as you are Senator Oko-Po, I am Senator Ek.”

Nower Jebel holds up both of his hands in a placating gesture. “Please, please, we should all endeavor to keep civil—”

“Stop.”

That word comes from of the mouth of the chancellor’s Togruta adviser, Auxi Kray Korbin.

Everyone does as she commands. Auxi stands and puffs out her chest, her chin lifting so she can—even at her diminutive height—seem to be looking down on them. The adviser says: “The chancellor has made herself clear. This meeting is over. We will see you all on Nakadia.”

She waves her hand dismissively—the gesture one makes when sweeping dust off a forgotten shelf.

As Ek leaves, he speaks loudly to the Abednedo, Senator Bushar. His words are meant to be heard, and he even looks over his shoulder as he says them: “I wonder if Tolwar Wartol would be so rude…”

His words linger like a bad smell as they all filter out the door.

All except for one.

Sondiv Sella.

The councilman represents Hosnian Prime. They have a senator, Yuprin Arlo, but Sella serves to help wrangle the different committees and subcommittees. He is new, but his help has been profound. Currently, he stands there, a small, strange smile on his face.

Auxi bites the air when she says: “I said the meeting was over.”

He offers a self-effacing chuckle. “Oh. I—I just wanted to ask the chancellor how she was doing. I know she was in the medcenter for an extended critical care period and I thought—”

“I’m fine,” Mon says, summoning a smile. “My arm is not yet at one hundred percent, but with my therapy exercises, it improves a little every day. They offered me a mechanical limb—but I said I wanted to try to keep mine for a little while longer.” She thinks but does not say that she fears what it means to have a prosthesis. Mon knows it is an unfair assessment, but something about having a metal arm would make her feel less than she is, now. Inhuman. Unliving. Her mind conjures the implacable mask of the Empire’s cruelest enforcer, Darth Vader, and she shudders. “But I am well. I appreciate you asking. You might be the only one who has.”

“I know it’s hard out there right now,” Sella says, a little hesitant, as if he’s sure he might at any moment overstep his bounds. He continues: “I was a cargo pilot, you know. For the Rebellion. I looked up to you as a leader then, and I don’t blame you for Liberation Day now.”

“I wish others shared that sentiment.”

“They do. And they will.” He nods, stiffly. “I don’t have a vote to give you, but Arlo does, and I agree with him. I’d like to offer my help to you in whatever way I can. I’ll try to usher the committees along to fruition and s

ay a few good words on your behalf. For the election.”

“Oh,” she chirps sardonically. “Is there an election coming up?”

He laughs, though a bit nervously as if he’s not sure if this is a joke or not. As if maybe the attack those months ago did not merely injure her arm and shoulder but perhaps scrambled her poor brain, as well. “I…”

“I was making a joke. Something I’m not very good at.”

“Of course.” He forces an awkward smile.

“Thank you, Councilman.”

“Thank you, Chancellor.”

And with that, he’s gone.

Auxi lets out a frustrated breath and pours two mugs of Deychin tea. Floral steam rises. Mon lets it bathe her chin and cheeks and closes her eyes for a moment, relishing the momentary peace.

“I could put brandy in it,” Auxi says.

“Tempting. Sorely tempting. But no,” Mon says with a sigh. “Last thing I need is for Ek to storm back in here and smell that on my breath.”

“He’s a pompous bombast. History will make him marginal.”

Mon sips the tea. “He’s hard in the bag for Senator Wartol.”

“Don’t worry about Wartol. In a few months, he, too, will be marginal.”

“Oh, I rather doubt that. How are his numbers?”

Auxi gives her a look. No, not a look, but rather the look: a look dripping with such incredulity, it could fill a cup to overflowing. “You don’t really want to play that game right now, do you?”

“I do.”

“As your adviser, I strongly advise you to sit and drink your tea. And I also advise you to find a second adviser. Hostis…” Her words trail off, broken by a fracture of grief. The chancellor knows that her two advisers did not get along very well professionally, often fighting fiercely from two diametrically opposed points of view. But at the end of the day, they were friends. They drank together. They ate together. Their families did the same. Then his life was cut short by an assassin’s blaster on that fate-dark day. “Hostis is gone, and we need someone like him. We need his voice.”

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

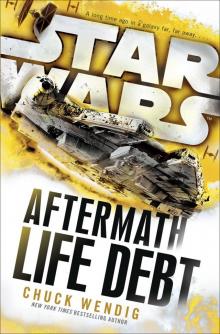

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt