- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Double Dead Page 3

Double Dead Read online

Page 3

The sun began to bleed across the horizon like the yolk of a runny egg.

He smelled flowers: tulips, he thought. He put his palm down on a carpet of pink: cherry blossoms. It really was spring.

His jacket began to smolder as dawn’s fingers caressed the length of his body. In a minute or two, that caress would become a fist, and that fist would enclose him in a fiery grip and cook him like a hunk of meat. A small part of him felt okay with that: this, after all, was the first time he’d seen the dawn in a very long time. He’d long learned that even the opening fanfare of sunrise was enough to give him a bad case of sunburn, and so come 4:30AM every night he’d retire to his Soho apartment (his belly fat with the blood of some club whore), shutter the windows, lock the dozen locks, and climb into his bed in a perfectly darkened room.

That was a damn nice bed, too. Memory foam. Way he sank down into it gave him the embrace of the grave with far greater comfort. And his sheets! Egyptian cotton. A thousand-thread count. Cost him a pretty penny. Well. It cost someone a pretty penny. All luxury like blood, always pilfered, never his own.

But all that was gone now. He couldn’t imagine going back to that apartment any time soon. The place was probably overrun with a bunch of hipster artist asshole undead, milling around in thick black eyeglasses and drinking shitty working class beer and spilling it on his glorious sheets and divine mattress.

He felt his skin grow warm.

He continued crawling, but he wasn’t even sure why.

He shut his eyes.

And then: mud.

His fingers sunk into mud and before he knew what was happening he was sliding down on his belly like some dipshit penguin—the brown turbid waters of the Hudson rushed up to meet him and he took in a mouthful of the foul river.

Coburn drifted down, the lazy current dragging him along.

All went dark as morning rose.

CHAPTER FIVE

Blood and Dreams in Dark Water

Once more, Coburn dreamed.

Daysleep was often without dreams, the landscape as lifeless and black in his own mind as it would be in the crypt. For all intents and purposes, during the day he fell into the same slumbering coma enjoyed by all the world’s corpses (except now, where the world’s corpses were a restless army of the hungry undead). It was different when he was hungry, though, and even worse when starving. If he went to bed in the morning without feeding, the dreams crept in at the edges: the darkness brightened at the margins with gray images as spectral as cigarette smoke.

The dreams were shaky, uncertain, hard to find.

But they were there.

He could feel carpet under his hands.

A dark shape—an evil shape, far more evil than he—stood behind him; he could not see this shape but could only sense it. Eyes at his back. A shadow lurking.

Somewhere he heard a girl’s cry: a young girl.

A lock of hair in his hand—the girl’s hair, he thought. Blonde. Curled at the end; a pigtail. Smooth and sweet and smelling of honeysuckle.

Then: blood and pain and screams and a curtain of misery drawing tight across the dream until—

Until as before, he was awakened by blood. This time, not running down from above but rather caught on the river’s murky current.

His eyes opened. The dream fled to the darkest corners of his head. He found himself underneath a sunken, overturned rowboat. Catfish, slimy and slick, fled him as he jostled to some semblance of life.

The blood was like a trail of breadcrumbs. He planted his feet on the boat—which had stuck partly in the mud and rocks at the bottom of the Hudson—and pushed off, swimming up-river, a shark in search of a meal.

Carl took his rusty pocket knife, slit the tabby cat from neck to nuts, worked his dirty fingers up under the feline’s pelt. He’d already bled the cat out and burned all the fur off, which elicited a smell that once upon a time would’ve made his throat close up, but these days, it only served to make him hungry. The cat still had a little blood in him, though, and it dribbled into the cloudy waters as the sun set at the far edge of the dead city across the way.

From behind him: a low and little growl.

He turned to the skinny black-and-white rat terrier in the rusty cage behind him. It was really just a guinea-pig enclosure, but still served as a make-shift trap.

“Shut the hell up,” Carl said. “Your buddy here is dinner, and tomorrow morning, you’re breakfast.”

The dog keened in the back of his throat. Carl didn’t care. He didn’t like dogs, he didn’t like cats. Didn’t like people, either, actually. This whole zombie apocalypse was working out just fine for him. Gave him lots of time to himself. What few survivors he’d met, they didn’t know how he so easily stayed alive. Or stranger still, how exactly he’d kept his paunchy belly.

“It’s easy,” he told them. “I stick by the river. The rotters won’t cross water. I just wade in and go far enough out and they mostly gather at the shoreline till they get bored. A few might stumble out into the Hudson, but those dumb fucks don’t know how to navigate. They get stuck in the mud or pulled along by the current, and I just watch and wave. If I got to, I get in a dinghy and hang out in the middle of the river for a few hours.”

But, they always asked, that doesn’t explain how you’re so well-fed.

Carl laughed, then, and taught them his trick.

A few hours later, they’d be cooked up over a fire. Parts of them dried for jerky. Bones saved for broth. Thigh meat in his belly.

Guy’s gotta do what a guy’s gotta do to survive.

But it had been a while since he’d seen any survivors. He’d camped at this spot for a good six months now, because it was a great place to lure the living. He clung to the river’s rocky shore, yes, but right there—no, really, right over there by about fifty yards—was a helipad, and next to that, a parking lot.

And beyond the parking lot was a hospital. Palisades Medical.

People loved hospitals. Thought they were safe. Thought they could find medicine. What assholes. Hospital was the worst place to go during the apocalypse. Medical services were barely enough to handle the day-to-day of normal living. Carl once sliced open his thumb when he was preparing a pheasant for taxidermy (that was what he did in his former life, and what made him so good with the knife), and he waited in the emergency room for six hours. Bleeding on the floor. Nurse would come along periodically, drop a towel under his hand and collect the one she’d deposited an hour before—a towel soaked with red.

If they couldn’t cope with a bleeding thumb, did people really think a hospital could handle the end of the world?

Hospitals were the first place the military hit—flamethrowers in the hallway to cook the sick and make sure they didn’t come down with a bad case of the corpse-walk flu. Hospitals were the first place that looters hit, too. It was a goddamn charnel house in there. Burned bodies under sheets. A handful of rotters trapped in the hallways, fumbling around like idiots.

And yet, survivors always showed up. Few got away from him. He offered them a meal: some fish, some cat jerky. Then he drugged them with the tranquilizers he found inside the Medical Center. Or, if he didn’t have the opportunity, he beat them over the head with a bat or stabbed them repeatedly. Death was death however it was achieved, and he found that drugging them made the meat a little goofy. Which was fun to eat, but it slowed him down.

Still. By now Carl wondered exactly how many survivors were left out there. Last batch he saw come through here didn’t stop in the hospital: a big ol’ rickety RV came bouncing down River Road. They were here, then they were gone.

Headed West, he suspected. Lots of survivors talked about heading West. They’d all heard the stories, and he guessed in a way it made sense. Midwest was the breadbasket of America, but was suspiciously devoid of people. Most of the country’s population lived at the country’s edges: East Coast, West Coast. Middle was a mushy nowhere wilderness. Iowa? Indiana? Arizona? Not a whole helluva lot out ther

e. But people spread apart meant the sickness didn’t spread so fast. Gave people time. Let them get smart and prepared.

Rumors went that the country’s breadbasket was a safe haven. That the country still ‘lived,’ now out there in the middle. Red States, triumphant.

Whatever. Carl didn’t buy it. World was fucking ruined.

Besides, this was his home. He’d rather die here with his belly full than live a full life as a resident of, what? Nebraska? Piss on that.

The terrier behind him started to growl again as he let the cat’s internal organs plop down and splash into a pot he held beneath the dead kitty.

“Pipe down, pooch,” Carl said, growling right back. Except in the evening light he could see the dog was no longer looking at him.

The dog was staring out at the dark waters.

Strange. Or not, since dogs were basically morons.

Carl went back to gutting the tabby.

Then: a bloom of mud up through the dark waters. About twenty feet off the scum-slick waters. Might be that the catfish are restless, Carl thought. They were morons, too—didn’t take much to nab a catfish. Few pieces of bread in the water and they came up with their big dumb mouths open. Easy to hook. Could just reach in and grab ’em if one were so inclined.

Carl set the cat down on the rocks, gingerly took a few steps out into the water. It was cold, but he didn’t mind. Later he’d light a fire and dry off (if it brought the rotters, he’d just burn the lot of them—the pile of charred zombie bodies around his campsite showed just how willing he was to make a stand).

He let his hands float into the water. He pulled a few dry bread hunks—he called them ‘croutons’ even though they were just rock-stale moldy chunks of French bread—and let them float out into the water.

The mud stirred.

Gotcha, he thought as he saw a shadow rising from ten feet away.

Oooh. This catfish was a big sucker. Good eats.

He bent his knees. He leaned forward.

Then the catfish shot up out of the river and Carl screamed.

Coburn kicked up out of the water and wrapped his hands around Carl’s throat—he didn’t know the man’s name, of course, and didn’t much care. This sodden fool with his pooched-out belly and his greasy, matted beard was going to serve as the first true meal that Coburn had consumed in a good long while.

As Carl screamed, Coburn ripped into his prey’s neck with his pair of mean fangs. His incisors were curved in and back—like a snake’s. When he closed his mouth, they fell neatly betwixt his lower teeth, his tongue slumbering atop them. But even better, the toothy curves let him bite down and dig in real good; anybody wanted to rip away from his bite they’d have to lose a big fat chunk of neck to do it.

Normally, he wouldn’t be this crass. Generally, he wooed his victims a little bit: a little talky-talk, a little hypno-gaze, a little here, listen to my suddenly eerily lyrical voice, and then settle in low and slow for a bit of bloodletting.

But hell with it, Coburn was hungry. This was the equivalent of ripping into a candy bar with the wrapper still on.

Carl cried out. He beat uselessly at Coburn’s side.

Blood, hot and sticky, filled his mouth. He was like a kid guzzling chocolate milk: he couldn’t stop and he didn’t want to. He needed this.

Wasn’t long before Carl went limp. Coburn kept drinking.

He kept drinking until his tongue played in the neck wound, licking up whatever last vestiges he could of his victim’s juices.

The body fell into the water. Well, all of him except the head: the head smacked against the rocks, thudding dully like an unripe cantaloupe.

The rest of Carl just bobbed there in the muddy river.

Coburn laughed. Wiped his mouth. Then, with his legs—wholly repaired now, not a bone chip or taut tendon out of place—he marched his ass out of the water.

Further, he felt an itchy tingle in a space above his hand, a phantom twitch. He watched as his middle finger grew back, sinew threading around a stretching bone, blood and flesh knitting together.

The vampire stretched.

He noticed then the dead cat. The vampire couldn’t help but wonder if it was curiosity that killed this beast.

Then: a growling. He spotted the little terrier in some kind of makeshift bird cage. The stubby little dog snarled at him. He met the animal’s gaze and did a little of the old eye hoodoo, then shushed the dog.

“Shhh,” he said. “Chill the fuck out, pup. Last thing I need is for you to call a gaggle of undead assholes my way. Is it a gaggle? What is it? It’s a school of fish. A murder of crows. A parliament of owls. What’s a bunch of fucking zombies? A cluster? A cadre? You know what? I’m going to go with a fuckbucket of zombies. Sound good to you, pup?”

The dog kept growling.

That was unexpected. This little snarling cur was resisting his blood-sucker mojo. Had that ever happened before?

Instead, he tried a different approach: he snapped his fingers.

The dog sat down in the cage, and quieted its growls.

“Yeah,” he said, feeling pretty good about himself. “See how I did that, pooch? I did that old school.”

He bent down and unlatched the cage. Coburn reached in and grabbed the dog under his front legs. If the dog tried to bite him, he’d just snap its neck.

But the dog didn’t bite. Instead, it panted.

Coburn grinned, licked a little blood off a fang.

“I hereby name you Creampuff,” he said, chuckling. “Because you are going to be a delightful little snack tomorrow night.”

Then, dog under his arm, he took off walking.

CHAPTER SIX

Chuck Wagon

It struck him, then, as he walked down the two-lane road—a road littered with cars shoved into one another at odd angles, a surefire sign of the Apocalypse if ever there was one—that the clock wasn’t going to turn back. Things had changed (duh), and they weren’t going back. Sometimes you break something and make it better, but this wasn’t that: this was a broken world that wasn’t merely content to stay broken, but would continue to break down even further.

Just as rot had claimed the zombies, it had also claimed New York. It had probably claimed the entire planet, for all he knew.

Coburn approached this thought charitably, with a spreading sense of warmth and satisfaction—a good meal had a way of casting one in a pleasing glow, even if the rest of the world had gone to Hell in a hazmat suit. The blood in his belly was now working its way through his blackened heart, through the withered channels. It felt good to be fed. It always did.

And before last night, getting fed had been easy.

The vampire led an easy, spoiled existence. The last fifty years had been an endless all-you-can-eat buffet. Manhattan had a population of almost two million, and that didn’t even count the millions who came in and out of the city each day as workers and tourists. Coburn sat in the midst of this like a glorious tumor, funneling fresh blood supply into his mouth night-in and night-out. He wasn’t really all that good-looking: his nose was a bit crooked, his teeth were a little fucked up. He was lean and lanky and had dark gray eyes that nobody in their right mind would’ve called ‘friendly.’

But being a vampire came with an unholy host of perks. With but a thought he could turn his voice into an angel’s song or a devil’s cry, he could blink and make his eyes as calming as a hot spring or as bleak and endless as a black hole. Didn’t hurt that he could snap even the toughest sonofabitch alive clean in half. Anybody got wise to his hypno-bullshit, he could break their necks easy as snapping a rib of celery.

Hell, most of the time none of his tricks were even necessary. The city that didn’t sleep was also a city that supped on sin. Drunk chicks. Meth-heads. Party-till-dawn-with-sex-drugs-and-techno-music. Blood thick with narcotic bliss.

God, he hated that fucking music. Didn’t anyone know how to play a goddamn electric guitar anymore? And the things they drank, the drugs they did. Nobody s

eemed to enjoy a good shot of cheap whiskey. Or a spoon full of black tar heroin. It was all artisanal cocktails and designer drugs. Made him sick. Made him want to puke up a bucket of blood.

This generation was the worst. Generation of weak-kneed hipster emo shitbags. A poor facsimile of their parents—and, frankly, those people were awful versions of their own parents, too. Generation after generation of bad duplicates. Like a letter run through the copier too many times. After a while, you couldn’t even tell what it was trying to say anymore.

That was why he didn’t feel bad about killing all those people. He went out of his way to select victims from the ranks of the douchebags, the asswipes, the hypocrites and bullies. Not because he had a conscience but rather because…

Well, it satisfied him.

Sure. Once upon a time he’d held onto some faint memory of a conscience. A glimmering, fragile little thing. Like a snowglobe or a porcelain pony.

That fragile thing had long been crushed under a black boot. The reality of what he did—of what he was—didn’t leave much room for guilt or shame.

Besides, it wasn’t like he killed every victim. Most of them he let go on their merry way. If only because disposing of bodies was an arduous task. Dumpster? River? Acid bath? Who had the time? Far better to drink a little, then send them on their way drunk and confused and without the memory of what they had done (or what had been done to them). Of course, sometimes they tasted so good…

At which point, well. Dumpster. River. Acid bath.

Now, though, everything was different. An obvious statement—what with the plants pushing up out of broken highway, the pile-up of rusted cars, the roaming hordes of slavering undead, only a mule-kicked blind dude could suspect that the world hadn’t pretty much shit the bed. But what struck Coburn was how it had changed for him. He had always been solipsistic, of course, occasionally convinced in the wee hours of the morning that all of the world was but a figment of his diseased imagination… but now it really hit home. The buffet had closed. The endless line of willing and drunken and drugged-up victims (queue forms in the rear) was done funneling their life source into his open and eager mouth.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

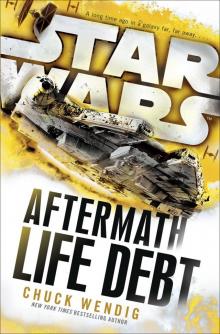

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt