- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Page 20

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Read online

Page 20

“No. Where is everyone else?”

“I don’t know.” Sinjir winces. “I lost Ek, too.”

“Bloody kriffing hellstar, Sinjir.”

Don’t worry, I’m just as disappointed in myself. He says nothing and gets moving, cleaving a hard line through the crowd of senators, looking for Ashmin Ek or Nim Tar or Conder (please be all right) and seeing none of them. He hops down off the farthest patio, onto the fibercrete street—he does a loop around the whole restaurant. He moves past the trash compactors out back, feet splashing in puddles from a recent rain. Then he moves up the other side of the building, down a narrow alley—

There.

Ashmin Ek and Nim Tar. The man from Anthan Prime is shorter than the Quermian, and yet somehow seems to lord over Nim Tar—Ek is seething. He’s got the long-necked alien by the scruff of his shirt, and with his other hand he thrusts a smug, accusatory index finger up in the alien’s face. Sinjir begins to march right toward them.

“Hey! Hey, stop right there,” he says before a plan actually forms in his head. I’m not security bureau, what am I doing? They turn toward him, looking like children with their hands caught in the sweets drawer.

Ek’s eyes flit to him. And then past him. As if—

Sinjir hears the scuff of a boot.

There’s someone behind me.

Something hard clubs him in the back of the head. A white flash pops behind his eyes, and it’s lights-out even before he hits the ground.

Coruscant is in chaos, and Mas Amedda is trapped.

He’s a prisoner of his own Empire. Those few remaining here in the impenetrable Imperial Palace are keeping him to his quarters. He has not left in months. Those present are loyal not to him, no. They belong to another: to Gallius Rax, the true keeper of the Empire’s fate and fortunes.

Rax sent him a handwritten letter—a rare thing to see, something only Palpatine himself was known to do from time to time—when this all began. It said, quite simply:

Glorious leader of the Empire,

I have taken Jakku. I have brought the Empire with me. You are still its leader in name. But you will be confined to your quarters until it’s all over. Do not try to leave. The doors are sealed (even the ones to the balcony, in case you entertained the idea of jumping), and any attempt to escape will be met with reciprocal violence meant to hobble you. I assure you, this is to keep you safe so that you may lead us again one day.

With great honor and respect,

Counselor Gallius Rax

What a pompous gas-bladder.

Rax was making no joke when he said he would hobble Amedda given any escape attempt. Just days into his cozy imprisonment, he tried to assault the two guards outside his door. He broke a plate across one’s head, threw a clumsy, telegraphed fist at the other. They handily dispatched him. Before he knew what was happening, a boot connected with his knee and he went down on the floor. One grabbed that leg and gave it a twist—the tendons tweaked and he couldn’t walk for days. Even now it gives him some trouble, with lightning whips of pain going up from his heel and into his hips. Woe and misery.

They bring him food—good food, not victuals fit for an Emperor, no, but it’s not gruel, either. Most days he’s alone, the exception being when they bring him those meals. He wondered at first why they didn’t just kill him. Why would Rax want him around? Then they showed him. Blaster pressing hard against the back of his head, a band of ISB agents forced him to record a holovid, thanking the troops for their service, thanking Gallius Rax for his military leadership, and assuring the Empire that victory would soon be theirs. They force him to do this from time to time. Once every month or so. It is soul crushing. He’d rather die.

(Though sometimes, that desire to find death is supplanted by something else: a parade of fantasies where he wraps his fingers around the neck of Gallius Rax and crushes the man’s windpipe.)

For a time, he hoped that Sloane was his salvation. They had a common enemy. But Rax found a way to end her. Lured her to Chandrila where, as the rumor goes, she fell off a skybridge to her death.

And now Mas Amedda has nothing and no one. He looks around his quarters. It is filthy. He has not washed himself in days. The room’s practically a midden heap at this point. Even his clothes are dirty. He would send them down the laundry vacu-tube—but that stopped working days ago.

Instead, he sits. He makes tea. He stares at the wall.

Inside this room, all is quiet and serene.

Outside in the city, madness has taken hold. He can see it from his windows when he chooses to look. Once in a while, an explosion will bloom in the distance. Anytime he opens the blinds, he can spy wreckage—usually Imperial, an ISB speeder or ship, sometimes crashed into the ground, sometimes into a rooftop. When they bring him food, he asks questions: What is happening? Who is out there? Are we safe? The only answer he gets is that he can be assured that the Imperial Palace is impenetrable. Then the guard will say something along the lines of, “The city is fine and remains under ISB control.” Which is a lie so obvious it’s like an ugly nose: Everyone can see it, even the one who wears it.

This is the best that Mas can figure: They have lost Coruscant.

Given that he has not seen New Republic ships, he wonders to whom it has been lost. Is there still an Imperial blockade in space? Or has the criminal underworld finally ruptured like a straining boil? Have the inmates taken over the asylum? He always warned Palpatine that curating such a close connection to the underworld—and keeping them so near—was a dangerous gambit. Mas Amedda is a creature of law and order—a man of numbers, a man of rules. Cozying up to scum like that always bristled him.

Though he never said much in objection, did he? The Emperor had his design. He did not brook dissent. He did not brook something so disagreeable as a dubious glance. Palpatine only accepted advice when it was asked for—and never before.

The Empire. What a grand and malignant failure. A pile of waste, and Mas Amedda is seated precisely at its pinnacle.

He wants to weep. But he has nothing left.

He sleeps for a time.

Then, a noise. It must be mealtime once again for the prisoner.

No. This sound is coming from…

The laundry vacu-tube?

It’s faint, the sound. A thumping here. The straining of thin metal there: da-dunk, barrump. A faint susurrus following.

Ah. Someone is, at last, repairing the damnable vacu-tube. Well, at least he’ll be able to get his clothes clean once again. If he cares enough to bother. And maybe he doesn’t.

With that mystery solved, Amedda again drifts off to sleep.

That is, until another noise startles him awake. This time, when his eyes pop open, he discovers with bowel-clenching shock that he is not alone.

He is, in fact, surrounded.

Filthy urchin children form a half circle around his chaise, and their presence confirms for him what he has long feared: His mind has been well and truly lost and he is now in thrall to a very vivid hallucinogenic life. At the fore of this vivid delusion is a soot-cheeked redheaded boy, his lip cleft by a fishhook scar, giving him a natural sneer.

Naturally, the child has a blaster. They all do.

“Go on, do it,” Amedda says drearily.

The boy seems taken aback by this. He shares looks with the other five children. A girl with dark braids forming a crown on her head makes a sour face. “You want to die?” she asks. “Iggs, you hear this bugger?”

The sneering boy—Iggs, apparently—lifts the blaster. “Well, Nanz, I suppose we oblige this leech and send him on to the next life.”

He lifts the blaster, and it’s then that Mas Amedda begins to cry. The tears are not tears of fear or hate or rage. They are the blubbering, plaintive cries of a man set on the edge but never allowed to come away from it—nor allowed to leap over its precipice. Here, finally, a release awaits. Even if this release is the dream of a sleeping mind or the vision from a broken one.

The blaster

barrel, like a black eye, stares at him.

One of the other children—a bug-eyed Ongree boy—twists the mouth that sits in the center of his bulbous forehead and says to Iggs: “I don’t think this is gonna work, Iggsy.”

“Bah, kriff it, I think you’re right, Urk,” the towhead says. He lowers the blaster. Amedda shakes his head.

“No! It’ll work. Just do it. Please.” He paws at the weapon, but the boy pulls it away in a taunting gesture.

“What am I missing?” Nanz asks. “Let’s ax the monster before anybody hears us! We have to get back out, you know.”

“Look at him,” Iggs says. “He’s not who we thought. This blue bucket of flab couldn’t lead a fly to a stack of dung much less the whole of the Empire. We pop him, we probably do him and the rest of the bucketheads a favor.” The children all look to one another and seem to come to the same conclusion with a series of half shrugs and nods.

Amedda presses himself further into the comfort of the chaise. “What will you do, then?”

Nanz says: “I guess we haven’t figured that out, yet.”

“Who…who are the lot of you?”

Iggs lifts his chin with pride. “Anklebiter Brigade. Or part of it.”

One by one, they identify themselves.

“I’m Iggs,” the redheaded boy says.

The girl with the braids: “Nanz.”

Bug-eyed Ongree: “Urk G’lar.”

A pair of Bith who may be twins or who might just be Bith who look like each other (Mas Amedda has a difficulty differentiating them) name the other: “He’s Hoolie.” “She’s Jutchins.”

“Wenchins,” says the last, another human boy.

“How’d you get in here?” Amedda asks them.

The Ongree, Urk, says: “Laundry tube. We broke it. Climbed up. Big enough for a kid to get through.”

How foolishly simple, Amedda thinks. And then comes the mad irony that Imperial engineers and architects were very good at creating very narrow—and very vulnerable—spaces in their designs. He begins to wonder if they had rebel collaborators building in such weaknesses…

“Help me escape,” Amedda says.

“You must be a real dum-dum,” Wenchins says.

Iggs waves it off. “Can’t fit you down the vacu-tube.”

“I can get us executive access to the turbolift. We just have to clear the hallway. We get to the lift, I can get us out of here. The hallway has three guards. I cannot overpower them, as I have no weapons. But you…you have blasters. Help me escape and I’ll help you.”

Again the children confer silently. Raised eyebrows all around.

Urk leans in, staring with those big yellow eyes. “What’s in it for us?”

“You’re rebels?”

“Of a sort. We rebel,” Iggs says.

“Get me clear, I can turn myself in. I’ll give the Republic the codes to open the doors to the Imperial Palace. I’ll tell them everything. I’ll surrender the whole Empire.” Of course, Mon Mothma did not accept his surrender last time, but these children do not know that. Further, maybe he can offer more this time. Maybe he can do it right. “Please.”

It’s Iggs that finally nods and says, “Deal.”

“He could betray us,” Urk says.

“Enh. He’s done for. I figure he tries that they’ll just lock him back in here. Look around—this lump is just a prisoner in his own chambers.”

“But we could die,” Nanz hisses in his ear.

“That was always on the table,” the boy says—a surprisingly stoic thing to say given his age. But Amedda fears this child has seen more than most Imperial bureaucrats ever have. “We die, we die. Least we die with our hands free and not tied behind us. Let’s get it done.” To Amedda, Iggs says in a low voice: “We’re going to get you out of here. But if you try to twist your way out and mess with us, I’ll shove you so far down that laundry chute you’ll wish you were back here sleeping in your own filth again.”

“Deal,” Amedda says.

“Deal. Now let’s get you to the Republic.”

The Observatory’s defenses made short work of the Hutt’s caravan, but Gallius Rax can see that, regrettably, they failed to finish the job. Now night has fallen and his quarry is positioned defensively behind pillarlike plateaus down in the valley. He flicks from screen to screen, watching. Sloane and someone else—some man he does not know—are behind the eastern pillar. Niima and some of her Hutt-slaves are hidden in the shadow of the western plateau. The good news is that they’re all trapped, pinned there by the turbolasers. They could try to run, but they would end up like the rest of the caravan: smoking wreckage and tangled corpses.

Rax remains down in the bowels of the Imperial base. The sentinel stands in the corner, projecting images from the center of its hand.

In walks Tashu. And with Tashu comes Brendol Hux.

“I have retrieved him,” Tashu says with a dramatic bow.

“It’s late,” Hux says, his lips smacking drily together. “What is all this? Why am I summoned at this hour?”

It takes a moment for Hux to regard the strange scene: a spare room with dark blastocrete walls, a red-robed sentinel with Palpatine’s face, and images of the Jakku desert projected into the air.

“I need your help,” Rax says to Brendol Hux.

“Wh…what kind of help?”

“I need to know: Are your recruits ready?”

“I need more time…” Hux flinches. “They need more time.”

“They have no more time. Prove your worth to me, Brendol.”

Hux’s eyes search the screens and the sentinel’s flickering face, trying to make some sense of all of this. “I…”

“Prove yourself and I’ll tell you what’s really going on.”

“I don’t understand…”

“Fail me and you will spend the rest of your days wandering this graceless desert.” It is a bold offering. Rax knows full well that Hux could try to leave here and tell the others in the council what’s happening. They could attempt a coup against him, though it would not succeed. Still, Brendol Hux is not a popular man. He isn’t army, he isn’t navy. He’s cold, smug, stubborn. He spends his time alone. Even his own son stays away from him—and that boy has no friends here, either. With the fall of the Empire, Hux and his son have been increasingly alienated.

And this is a way back in. A way out of isolation. A reward, dangling there in front of him.

Will he jump for it? Or will he wilt like a flower in this dead place?

Hux nods, puffing out his chest. “They’ll do what you need. Just tell me what it is and I will have them ready to serve.”

Rax smiles. “Good.”

—

“What happened down there?”

Norra asks because the fuzzy view through the quadnocs—stolen from the Corellian shuttle, now parked behind them—gives no meaningful answer. Jas flew the ship up here to the effective end of Niima’s canyons and caverns, parking it atop a tall, toothy ridge that overlooks a broad valley that opened up in the desert. There the valley extends outward, guarded on both sides by a gauntlet of plateaus and megaliths, striated in the colors of fire and blood. But it’s not the valley that puzzles them.

It’s what’s in it.

Down there, about five klicks out, is a caravan in ruins. Something laid waste to it. A dais sits collapsed, broken in half like a shattered table. All around lie the smoking remains of wheel-bikes and speeders. Pack beasts dot the area, dead. And there are human corpses, too. White as bone. Painted that way, Jas said: Hutt-slaves belonging to the slug boss, Niima.

Niima is there, too. Norra spies the long-tailed slug waiting on this side of one of the plateaus. She’s not alone—some of those white-painted slaves crawl all over her like bugs swarming a fallen log.

Norra leans into the crook of where two jutting stones meet, then turns the ’nocs east—

That is where she finds Sloane.

Sloane’s hunkered down there between the wall of an an

vil-like plateau and a small pile of ancient broken boulders. The admiral, too, is not alone: Someone is with her. A man, hiding behind a spire-like stone.

“My take,” Jas says, “is that we’re talking turbolasers. Look past the broken caravan. Another couple of klicks.” Norra refocuses the quadnocs for a more distant view—they’re night-vision, but the thermal view still distorts what she sees. Just the same, she sees something out there. Something boxy, moored to the slopes of low mesas. Beyond that, there’s a final plateau that closes the valley: This plateau looks like an outstretched arm with a cupped hand at the end of it, as if looking to catch whatever might fall from the sky.

“I think I see them.”

“They’re usually for ground-to-air—”

“But like Akiva, they’re being used for ground-to-ground, too.”

“Correct. Which means they could tear us in half if we get hit.”

Norra stands and leans against one of the jagged stones. The ’nocs hang by their strap. “What do we do?”

“The more important question is, What’s your plan with Sloane?”

“I don’t follow.”

Jas crosses her arms. “We have two ways to deal with her. One involves capture and extraction. That means taking her back to Chandrila—or Nakadia, or wherever—to face a tribunal.”

“And the other way is to kill her.”

“Correct. Assassination. Here and now. A proper revenge.”

Norra knows what she wants to do. And Jas only makes that choice easier when the bounty hunter explains: “If we want her dead, we head in that direction, our cannons going at full blaze. She gets hit and dies, or she runs out into the open where a turbolaser turns her to dust on the wind.”

“And the other way?”

“That gets trickier. Because it means we need time to get her on the shuttle, and that area she’s hiding in doesn’t afford us much room. Pretty cozy down there, so our tail feathers will be hanging out.”

“Damnit.”

“The question is, Do you want justice, or do you want revenge?”

“I…”

Images flash. Sloane having Norra’s son thrown off a roof at the satrap’s palace on Akiva. Sloane escaping in a TIE fighter. Their fight on Chandrila—brutal, bitter fisticuffs. I want her dead and gone. I want her to pay. I want my revenge for all that she’s done. But other images cascade: Her son’s face. Leia’s, too. Everyone she knows makes an appearance—Sinjir, Solo, Jom, even Brentin.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

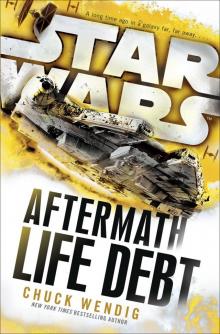

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt