- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Page 16

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Read online

Page 16

The figure in the cloak turns.

The face of Emperor Sheev Palpatine looks back upon him. That face flickers across the glass bulge of the droid’s mask. It is artifice, but even as a proxy it is close enough to the real thing to haunt him. Other sentinels were merely messengers: They appeared, gave commands, and were gone. But these, the ones reserved for Rax and their master plan, are smarter. They’re sentient. Though none truly match Palpatine’s strategic brilliance and his dark, terrible mind, they approximate it enough.

The voice, too, is close enough to curdle his blood. The droid sentinel speaks in Palpatine’s voice: “The farthest perimeter has been breached.”

“Show me.”

From the sleeve of the red cloak, the droid’s black metal hand emerges. In the center of its skeletal palm is a projector, and now that circle beams a holographic image into the air, gently turning.

The three-dimensional image shows a caravan traveling across the valley floor: wheel-cars and beast mounts and wanderers. At the end of it all is a raised platform held aloft on hover-rails, eased along by men holding heavy-gauge chains. And on that platform is a Hutt.

Niima.

The droid’s thumb flicks reflexively—like a spasm, but one that has a function. With every twitch, the image changes. It shows the caravan from different angles—sometimes at a distance, sometimes close. The valley is littered with cams, long hidden under the sand and dust or embedded in the rock. All part of a network that’s been in place for nearly three decades, now. The image suddenly zooms in on the platform, and Rax gasps.

The image shows a woman. Her black hair is pulled back under a winding of ratty ribbon. Her eyes are concealed behind thick goggles. Her skin is dark.

He knows her. He would know Grand Admiral Rae Sloane anywhere.

“She lives,” he says.

“And,” Tashu says, “she closes in on the Observatory.”

“How soon?”

It is the sentinel who answers: “Given rate of movement, three days.”

Three days. Good. That is plenty of time to end their journey.

To the droid, Rax says: “Arm the defenses.”

Sloane, I admire your tenacity. But I have to finish this.

Slow, slow, like a belly-slit-worm-struggling-through-a-rut slow. Rae Sloane walks alongside a massive platform—a stage, really, a dais on rusted hover-rails chugging and buzzing. It’s drawn forward by Hutt-slaves pulling on fat chains draped over their bony shoulders. On the stage sits Niima the Hutt, coiled in a nest of ratty pillows under a massive leather tent.

The Hutt sleeps. Snorting and snoring, bubbles of mucus burping up through her nose-slits. The occasional wind comes and tousles the filthy red ribbons tied around her many nodules and protuberances.

This is the rear of the caravan, but the stage and its riders are far from the sum of it; ahead walk dozens of Hutt-slaves. Others ride wheel-bikes or old speeders whose grav-lifts have broken and are now mounted atop rolling platforms, their engines converted from clean turbines to growling, smoke-belching loco-motors. Some ride leathery, reptilian beasts whose bodies are fitted with metal plates and crude bionetic enhancements like telescoping eyes or pneumatic jaws. All of it churns and trundles along through a sun-scoured, wind-whipped valley—and on each side of them stand spires of red stone and anvil-shaped plateaus. Like the guardians of a forbidden place.

Those plateaus cast long shadows across this deep valley.

“This is arduous,” Sloane growls.

Brentin Wexley looks up at her. He’s weary. Lines of frustration have been permanently etched into his forehead. His cheeks are reddened by the blowing sands. Her own cheeks must be stung the same way. Her goggles are already caked with dust, too—and, as she does every couple of minutes, she has to wipe them free with the backs of her hands.

The two of them hang back beyond the dragging dais. Though Niima sleeps, they dare not say anything against her within easy earshot.

“Progress is progress,” he says. Ever the optimist. Surely by now it’s just a show? “Our fates are married to the Hutt’s.”

“It’s been nearly a week.”

“I know.”

“We need to seize the moment. I’ve been thinking,” she says.

A look of worry crosses his face. “Do I want to know?”

“You do and you will and you’ll not dismiss me. I have a plan.”

“What is it?”

“The Hutt sleeps during the day. Which means that is the time to strike. Soon, even. Today.”

“Are you batty? Killing a Hutt is no easy thing—”

“We’re not attacking her.”

“Who? Her…people?”

She sneers. “Don’t call them people. They’re barely that anymore. They’ve been enslaved for so long they’ve been programmed into something else.” But even as she says it, she hears the way it must sound to him. Brentin flinches, as if the words were almost physical—the back of a hand swinging for him. “I don’t mean it like that, Wexley. They’re not like you.”

“It’s fine,” he says, newly curt. “Let’s not debate what makes us human. You want to attack the slaves, then. We don’t have weapons.”

“They do. And I am a weapon. I’m trained. I can fight.”

“We can’t fight them all.”

“I only need one or two. They have those wheel-bikes. We take out the riders and steal the bikes. Those engines must have some power. We grab one and we go. Fast as we can.”

“They’ll come after us.”

“I know. But what choice do we have?”

“We keep going. Same as we’ve been. Like you said, it’s been nearly a week. Why change course now?”

She steps in front of him and blocks his path. “Because I just thought of the plan.” It’s a lie, and he calls her on it, his voice low as he does.

“The plan isn’t even a plan. It’s so obvious, we could’ve done it from the beginning. No, what’s changed is you’re desperate. Hungry to have vindication and you hate that it’s delayed.”

“You don’t feel the same way? You want your vengeance, too.”

His face is suddenly stark with—what is that? Is it sadness? “Sloane, it’s not vengeance I want.”

“Don’t lie. If it’s not vengeance, then what? What drives you to be out here in this hell-blasted deadland?” She leans in close and lifts her goggles so she can stare at him with her cold, dark eyes. Rage flares up in her at the thought he does not share her desire for comeuppance. “You mean to tell me you don’t want to put a blaster to Gallius Rax’s forehead?”

“I do. Stars help me, I do. But that’s not why I’m here. I want to make up for what I did.”

It’s so absurd an idea, Sloane can’t help but bark an incredulous laugh. “Make up for what? Chandrila? Someone stuck a chip in your head, Brentin. You were dancing on the end of Rax’s puppet strings.” We all were. “You don’t have to own that. You can just cut his strings because it feels good to cut his damn strings.”

“I need to stop Rax because it’s how I show my wife and my son that I’m not the man on that stage. It’s how I fix what I did.”

Sloane grabs a fistful of his shirt. “You’re a fool. It’s vengeance that carries us. Forget everyone else.”

He pauses. The sadness on his face deepens. The look he gives her is one of…pity. “You don’t have anybody, do you? That’s why you don’t understand. There’s nobody out there who you love or who loves you back.” Those words are like a blaster shot to her middle—clean through, leaving a hole as big as a fist. He keeps going: “You have to have something or someone to fight for. Not just this. Not just…revenge.”

“I have what I have.”

“You have the Empire. You can save it.”

“This is rich. The rebel telling me how to save my Empire. My Empire? It’s dead. It died the moment it touched this planet. The only thing I have—and the only thing I need—is the look on Rax’s face as I take it all away.” She

looks over her shoulder at the caravan. Already their lagging is being noticed by the bone-faced acolytes. “I’m retaking control of this situation. You can come with me, or you can die a Hutt-slave.”

And with that, she turns and marches back to the caravan. Sloane is singularly focused—ahead, the slaves on wheel-bikes do loops in and around the caravan, the kesium fuel burning black out their tailpipes. She storms up alongside the dais, calculating her path of attack.

One Hutt-slave walks in front of her. He’s one of the few with a blaster—a rifle cradled in some creature’s rib cage, the barrel framed by a pair of broken tusks. One punch, and she’ll have that blaster.

That will draw attention. She’ll need to run and gun.

But that’ll time out right—the one on the fat-bellied wheel-bike doing loops will be within range. Take him out. Grab the bike. It’ll be like that time on Yan Korelda when she was just a recruit in the Empire and barely got away from a gang of rebel thugs after refueling her speeder bike. One of their blaster bolts literally cooked a tuft of her hair—she could smell it burning for hours after.

She charges forward. Past the dais. Past a duo of Hutt-slaves who babble at her as she pushes onward. Sloane has no idea where Brentin is—if he’s hot on her heels or burying his head in the sand. She doesn’t care. She can’t care. Her goal is the blaster rifle, then the wheel-bike.

Then Rax.

The Hutt-slave doesn’t even know to suspect her. By the time she’s upon him and he’s turning his head toward her—

Wham. She drives a fist into the back of his skull. His teeth snap together and he doesn’t even make a sound. All he does is pitch forward, face-planting into the sand…and as he does, she catches his blaster and wrenches it out of his grip. Now she has a weapon. Niima didn’t let her or Brentin have blasters—on this journey they’ve been nothing but spectators, buckled into a ride they didn’t ask to take. That changes now.

But the wheel-bike that had been coming her way suddenly kicks up a spray of sand and goes back the other way, its engine growling. No! Get back here, you Hutt-sucking freak. She starts to run, but now cries of alarm rise up around her—Niima’s slaves howling and calling for their mistress. And the Hutt does not disappoint: Sloane hears the mechanical gargle of the slug’s translator box as it transmits her rage to the world:

“STOP HER.”

It all happens so fast.

One slave comes up at her and she cracks the butt end of the blaster rifle into his chin. He swallows teeth and goes down, flailing—and two more come charging up in his place. Sloane raises the rifle, aims.

Two spears of laser light end them as she fires the blaster. Each slave goes down with a smoking hole in the center of his chest.

Something clubs her in the side of the head. Her ears ring as she tumbles to the sand, rolling over and reflexively holding up the blaster across her face just as a slave brings his sharpened machete down—thunk! The blade sticks into the side of the rifle. The slave struggles to extract it.

Someone tackles the slave from behind, knocking him back.

Brentin.

Wexley kicks at the freak with a boot, then grabs the machete with one hand and helps Sloane up with the other.

As he hauls her to standing, Sloane hears a sound: The hissing of sand, the chanting of the slaves, and it’s then she knows that something is coming.

Niima.

If Sloane has maintained one common belief about Hutts, it’s that they are indolent, lethargic creatures. They are called slugs for a reason. But Niima defies this handily. This creature is not some torpid glob. Sloane looks back over Brentin’s shoulder, and fear fills her empty spaces the way fire gobbles air—the Hutt slams down off her dais, hitting the sand with a cough of dust. Niima slithers toward them fast as a viper. Hutt-slaves cling to her like riders, their mouths open, their teeth bared. They have blasters. They start firing.

Sloane grabs Brentin’s arm and they break into a hard run.

Blaster bolts kick up sand around their feet.

Behind them, the hissing sound of Niima’s body sliding across the sand grows louder and closer. She has no idea how near the Hutt is to them—but it’s close enough that Sloane starts to smell the foul stink of the monster. She thinks to turn behind her and fire into the serpent’s face, but the slaves will just swarm her. No. The plan is the plan and she needs to stick with it: Get to the wheel-bikes. She takes aim as she runs, tracking one of the riders with the sights of her rifle…

But something distracts her. In the distance, far away in the valley, she spies a flash of light—something glinting off the high-day sun.

The Hutt roars behind her. A shadow falls upon her as Niima rises up, lifting her whole corpulent body with the sheer strength and will of her tail—

The air fills with white light. A shrieking pillar of green fire fills the space and before Sloane even knows what’s happening, there’s a thunderclap and she’s thrown to the ground. A column of smoke drifts from somewhere, and her eyes follow it to the source—

Niima’s hoverdais is collapsed into the sand, sheared in half.

The Hutt mistress herself is within spitting distance. The slug is dazed, tilting toward her side. Niima shakes her head as her reptilian eyes refocus. Sand streams from her crumpled, rotten skull.

The Hutt bellows something in proto-Huttese, but the translation is lost to another bolt piercing the air, and one of the wheel-cars suddenly flips up, turning once, twice, before slamming back down on top of one of the beasts. The creature screams as its back snaps.

Turbolasers. That’s what’s firing on them. Sloane knows that sound. That beam. She’s never been on the ground when they’ve been firing—and she’s never been the one in their sights—but she knows what they can do, and if they don’t move, they’re all dead.

Change of plans.

The wheel-bike won’t save her. But those plateaus? They might. She reaches down to find her one ally in all this—

Sloane looks over and sees that half of Brentin Wexley is missing.

Oh, no.

But then he sits up, sand and dust seeming to melt off him. Somehow a wave of it buried part of him. He coughs and hacks, but there’s no time for him to clear his lungs, so Sloane gets behind him and helps him stand.

She points. “The plateaus. Run.”

They run.

Just as another turbolaser blast turns one of the wheel-bikes to ash.

On the first day, five pilgrims depart from their starship and set out across one of the countless deep cave systems of Christophsis. They set out with great purpose, bringing with them a sacred gift that was stolen from this place not that long ago: kyber crystals, gems that grow at only a few precious spots here on this world. (Though much of this world is crystalline, the kyber crystals are considerably more rare.) The kyber crystals were taken from this world by the Empire and used to construct the world-killing laser of the Death Star. Though they were also used by the once peacekeepers of this galaxy, the Jedi, in constructing their lightsabers. Brin Izisca said that these must be returned from whence they came: Christophsis. To their, in his words, “home.”

One of the pilgrims is a droid—an MA-B0 cargo lifter droid they call Mabo—and he is the one who carries the crate that holds what was stolen.

On the third day, as they march up a steep rocky embankment studded with crystal spires and slippery with scree, Addar the human confides in his friend Jumon the Iakaru: “I don’t know why we are doing this.”

Jumon shrugs it off and growls, “Because this is what must be done.” His whiskers twitch when he says it, as if this explains it all.

And yet Addar—who is young, untested, and uncertain—persists: “I just mean, what’s the point?”

“Tonight, around the fire, we will watch the holovids again to help you understand.” And they do. When night falls, they start a fire underneath one of the vents leading out to the open sky (where Addar looks up and sees a spray of stars that gleam and glitt

er like the walls of these caves). Jumon has Madrammagath the Elomin set out the projector disk. From it emits the crackling, staticky holoform of Brin Izisca: the pastor and philanthropist who governs their faith and their community, the Church of the Force. The image of Izisca goes on about the heritage of the Force, about how all things are connected, and about how the Jedi do not control the Force but rather, are merely conduits for it—“antennae attuned to that cosmic frequency,” the man says, and even in the holoform it’s easy to see the wonder dancing in his eyes like torchlight. But Addar isn’t feeling it. Addar isn’t feeling any of it.

When the vid is done, Jumon must sense his apprehension and barks: “We do it because we do it. Because these must return home.” Jumon rolls over in his pack and goes to sleep.

And that’s the end of that.

On the fourth day, they enter the crystal forest. Here the trees are weak and wispy, their bulk more like threads than trunks, their branches like filaments—and yet they stand tall because they are encased in blue crystal. Some even grow up from the ground and marry with the ceiling. When the cave wind moves through them, it keens and moans, a shrill cacophony coupled with dread, groaning lamentations.

As the fourth day ends and the fifth day begins, Madrammagath consults with Uggorda the Duros. His cheeks lose their rosy bloom and his horns twitch as he says: “We are being hunted.” Uggorda confirms it, and she says: “Stay vigilant.” Given how rarely she speaks, the warning carries extra meaning, and fear scurries through every micrometer of Addar.

We shouldn’t have come, he thinks.

On the sixth day, Madrammagath is found dead. He goes off into the crystal trees to relieve himself, and he never returns. They discover his body, cut to pieces as if by saw-blade.

Jumon snarls: “Now we know what hunts us.”

“What?” Addar asks.

“Kyaddak.”

They do not stop to camp that night. They hurry on.

On the morning of the seventh day, they hear the Kyaddak: the tak-tak-tak of their many limbs, the click-click-click of their chelicerae. By midday, they begin to see their sign: scratches in the crystalline trees, gleaming silicate scat smeared across bulging rock. By evening, they see them: just flashes and shadows at the margins, far away and down branching tunnels, but closer than anyone cares to discover.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

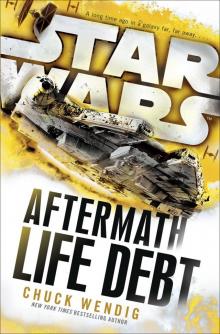

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt