- Home

- Chuck Wendig

The Raptor & the Wren Page 13

The Raptor & the Wren Read online

Page 13

A brightness comes in through the window. At first, she thinks it’s just the moon, but then she sees it’s more than that: it’s the moon’s light mirrored on a landscape of white. Snow, she thinks. Not much yet, but out there in the forest she sees white mounding between and up against the trees. Flakes whisper against the glass as they fall gently, lazily, unperturbed by wind.

Well, fuck all this beauty, she has to pee.

She yawns, staggers naked into the little bathroom. Miriam thinks to leave the lights off in case she wants to cool back down and rejoin Louis in bed, but already she feels alive—her skin tingling with the electric buzz of unswerving consciousness. She turns the lights on, and when she does, she is once more greeted by the shocking image of what has happened to her head.

Her hand runs across her scalp. The hair—so blond it’s the color of scarecrow straw, and cut so short she only has a couple inches to mess with. Her fingers slide through it. Some of it is mashed down, the rest rising in fickle peaks. She doesn’t look like herself anymore. That’s the point, isn’t it?

For a while after that night, the night Harriet came back, the night Grosky lost his head, they went from motel to motel, watching TV on whatever piece-of-shit boob tube the room had bolted to the wall. Wasn’t long before the news had her scent, which rattled her like a cup of dice.

For a long time, she’d lived her life at the periphery: a woman at the margins, a ghost who didn’t seem to have much effect on the world except for one person here, another there. She felt like one of those fish on the bottom of sharks: a shadow unseen, hiding in the belly of much meaner beasts.

But then Grosky showed up and revealed to her the world of Reddit—her as the Angel of Death, nameless and mythic. And then came the night Grosky died, and the news was over it like flies on a horse’s ass. MASSACRE IN PENNSYLVANIA. DEPOSED FBI AGENT SLAIN IN BRUTAL MURDER. Her name, splashed across the screen. Then they found the Reddit, too, and then it wasn’t just Miriam Black, but it was Miriam Black: Angel of Death. They had her number. They had her look. So, she chopped off her hair, dyed it bone-blond, and that was that.

When they came here to the cabin, Louis made sure the place had no TV. Even though coverage of her died down after a couple weeks—and no leads, thank whatever sick gods govern this world—he didn’t want her glued to it.

She found a better place here.

A place of peace. Wild woods. Dark forest. Distant cabin.

It’s nice. Like she’s no longer a part of the world. Like she’s gone back to the margins, back to the periphery . . .

Her bladder reminds her why she came in here, so she sits, she pisses.

Her mind continues to wander. Her natural inclination is to wonder and worry about what comes next, but lately, she’s been burying that inclination in the dirt of her own mind. And instead, she gives herself over to the bliss of the moment. Where she is—where they are—it feels good. It feels right. And a desperate little voice tells her, Maybe this can go on forever like this. This time away. This exile. Maybe this break in the status quo can become the status quo. What’s the saying?

The new normal.

Not like she ever had anything close to normal, anyway. The moment that crazy lady beat her half to death with a snow shovel—that set her on a path perpendicular to normal, far away from it as fast as possible.

But this, where they are now, it feels something like normal.

It feels something like life. Or a life, at least.

Above her head, in the corner of the room, a little house spider spins a web. Fat butt dangling as its tiny legs stitch the silk. “I’m just like you, dude,” she tells the arachnid in a low voice. “Just hanging out.” Hanging out away from everything. Staying warm. Staying cloistered. Fuck the rest of the world.

Miriam wipes, flushes, and decides she’s really truly awake.

She goes and puts on pants, a T-shirt, Louis’s big-ass frumpy barn jacket, and she heads outside. The cabin isn’t big, it’s barely two rooms without the bathroom, so she has to be quiet as she slides through the galley kitchen and to the door outside.

Outside. The air has a bite to it, but it also has that odd winter’s warmth—the snow falling feels insulating somehow, like it’s a blanket. Like it’s a skin on the world covering up all the exposed sinew and muscle left behind when autumn goes and winter strips everything down to the bone.

Of course, it’s not really winter yet, is it? The solstice is still a few weeks away. Wait, is it the solstice, or the equinox? Whatever. Fuck it. Miriam cannot summon the energy to care. The word they use, solstice or equinox, it changes nothing. Everything is a placeholder, a proxy.

Miriam draws the cold air into her lungs. She looks down the long gravel drive cutting through the pine. Louis’s pickup truck, the bumper since replaced, sits nestled up next to the little dark cabin. The air smells of burning wood from the pellet stove. Snow collects on her eyelashes and she blinks it away. The moonlight fills all the spaces. All is still.

Everything is quiet. No highway. No trains. Nobody yelling. No gunshots, no sirens, no TV noise, no nothing.

Her current fantasy is this: The world has ended and they are the only two left behind. It is a peaceful apocalypse as everything slows to an inevitable death, and they get to be here and ride the pony until it lies down beneath them and comfortably passes away. Then they crawl up inside it like it’s a tauntaun with its belly split, and they too go away with the world.

It occurs to her sometimes that thinking of things that way is pretty fucked up. Most people imagine themselves at the center of a living world. And here she is, pretending that the world is dead and she and Louis are the last witnesses to it.

That fantasy bubble is burst every morning when Gordy shows up to bring them the news or their groceries. And in those moments, her mind is like a wild horse that hates its stable—it busts out of the barn and gallops fast through signposts with names burned into them. Wren. Gabby. Harriet. Sometimes, she imagines the signposts are gravestones, and it helps her get back to the comfort of her fantasy.

Her breath gets ahead of her like an escaping ghost.

Miriam rubs her hands together.

It’s time to hunt.

She goes out into the trees. With the air so still, the only noises around her are those of falling snow and the munch-a-crunch of her boots pressing into the new powder. Soon, the cabin is just a spot on the horizon, and when she’s far enough away, she lifts her chin and closes her eyes and lets everything out of her head.

In the darkness of her mind, shapes stir. Like little embers burning in the night—stars, sparks, cigarette cherries. Each is a living thing. A bird. Many roost and perch, asleep: titmice, nuthatches, chickadees, cardinals. Hiding in nests, sleeping in tree hollows and dead stumps.

Others are awake. But it is only one she seeks.

There. Slicing the night on both sides, wings spread wide, comes the owl.

The bird lands with barely a flutter of feathers on a nearby evergreen. The branch dips just enough that snow slides off and to the ground with a flumpf.

Miriam opens her eyes. She regards the owl. The owl regards her.

“Hello, Bird of Doom.” That’s what she’s taken to calling it. When Louis’s friend, Gordy—their patron and sorta-kinda-landlord—saw that they had an owl with them, he blanched before getting excited. Gordy said in the nasal growl that marks his voice:

“My ex-wife used to hate those things. We had a screech owl in a tree outside our bedroom, making its sounds at night. Sometimes, it’d fly by and scare the panties off her. God, Marcia’d scream like a mouse just ran up her coochie. She said, They’re bad luck, Gordy! They fly by your window, that means you’re gonna get sick and you’re gonna die. I just know it. And she’d worry and worry about how it meant she was likely to catch some disease and it’d kill her.” He laughed like it was crazy. “She whispered to me one time, That’s a bird of doom, is what it is. Me, I like owls. Helps me sleep, knowing they’re

out there. And the fact that they upset Marcia just makes me like them even more.”

And so, Bird of Doom it became.

“You ready to scare up some prey?” she asks the owl.

Bird of Doom cocks her head like a confused dog, as if to say, Of course I want to hunt, you stupid hairless bear. Miriam gives a clipped nod, pulls the hood over her head, and lopes into the forest. The owl takes wing.

Through the dark woods, they hunt.

THIRTY-TWO

BLOOD AND BREAKFAST

The sun rises and shines through the trees in broad, crepuscular bands—the light catches in the last few flakes of snow falling, and it pools in the spatters of blood on the picnic table sitting out behind the cabin. It glitters and gathers.

Bird of Doom is on the ground nearby. She’s mantling—meaning she’s got her wings puffed up and pressed to the ground, making a kind of perimeter defense around her like she’s afraid some other owl is gonna cheat off her test. In this case, the test is a squirrel. The bird’s head dips and stabs underneath its wing shelter, plucking bits of stringy meat into its beak. Snap, snap, swallow.

Miriam has her own squirrel. Gutted and bled and skinned. Her hands are still red. This one’s cooked, though: with enough charcoal and lighter fluid, it was easy to get the fire going around four AM. And the cold air kept the squirrel fresh.

She pulls strips of meat off her own kill. This squirrel she killed—not in her own body but while riding the owl. Sometimes, Miriam puts herself inside Bird of Doom and takes over. That part is getting easy now. Hunting isn’t second nature to her, not like it is for the bird, but she can borrow the creature’s instincts—can feel the animal’s pull toward prey. It’s a helluva thing, feeling your wings out, your talons down—and pinning some unsuspecting woodland creature to the snowy ground. The hardest part about it is knowing to let go and not just greedily eating. Miriam needs to eat—Miriam’s body needs the nourishment, not the mind.

Which is what she’s doing now. Taking to the squirrel like she might take to a plate of stacked pancakes. Her teeth along bone, pulling meat.

“I’m not gonna eat yours, long as you don’t eat mine,” she says to Bird of Doom. The owl looks up, wide-eyed like, Shut up, pink-skin, I’m trying to eat.

The back door of the cabin pops open, and here comes Louis—blanket wrapped around him as he blinks sleep out of his eyes. He slides in next to her, gives her a kiss on the cheek, then nods in Bird of Doom’s direction.

“Owl,” he says. Then, to Miriam: “Another successful hunt, huh?”

Miriam mmmfs in agreement, slurping stringy squirrel meat into her mouth like it’s a wayward noodle.

“Didn’t scare me up one, huh?” he asks.

“Sorry,” she says. She holds the carcass at him. It’s charred in places where she overcooked it a little. “One last bit of thigh meat, if you want it.”

He waves it off. “It’s fine. We have eggs. I’ll make some.”

“Make some for me, too. Squirrel’s pretty lean.” She wishes they’d gotten a rabbit. Bird of Doom can nab bigger prey, big as a raccoon, possum, or groundhog. But those aren’t good eating, Miriam has discovered. At least, not just flung onto a little charcoal grill. Maybe a more nuanced chef knows what to do with raccoon, but right now she’s at the most Neanderthal, FIRE GOOD stage of cooking. Which is where squirrels and rabbits shine. For a moment, she lets her mind go—like a bike chain or a transmission slipping, it briefly goes to the owl. Her mouth fills with the taste of blood and meat: raw, fresh, like squirrel sashimi. It gives her a small thrill and then—shoop—she’s back.

Louis starts to get up. She grabs a fistful of the blanket, pulls him back down. With the taste of blood and meat on her tongue, she kisses him—her lips smashing against his, her teeth against his teeth. His moans meet hers. Miriam pulls away long enough to say, “Thank you.”

“I think I should say thank you for that kiss.”

“No, I mean—for this, for all of it.” If it wasn’t for Louis coming to get her that night, who knows where she would’ve ended up? On Harriet’s hook? In the back of an actual cop car on her way to jail? Would’ve been a manhunt. But Louis came and took her away, and he didn’t flinch when a mile down the road, an owl landed on the hood while they were at a stoplight. Miriam asked if the owl could come with them, and without missing a beat, Louis said, Anything for you.

And that was it. That was the moment she knew who he was, who she was, and how they needed to be together. Hell or high water. Till the oceans boiled and the sun went dark. They came here after that. He said they needed to hide out, and that he had an old buddy he used to work with at the trucking company, fella named Gordon Stavros. AKA Gordy. Gordy had this very remote hunting cabin near his house in the northeast part of the state, not far from the New York border. It was off the grid. Solar power. Wood heat. Louis cut a deal with him and that was that—since he was now an accessory to all of Miriam’s legal and spiritual sins, the both of them took the leap together, ejecting from normal life and going off to hide in the woods.

That was almost two months ago.

And now she doesn’t want this to end. She wants this cabin, this forest, her owl, her man, to be forever.

(A little voice pokes at her: Gabby. You’re forgetting about her, aren’t you? And Miriam has to shut that voice out. She has only so much love to give, and Louis has taken the leap—but maybe Gabby can be safe wherever she is. Even as she thinks it, it feels like a lie, like she’s denying the truth of both who she is and who Gabby is, too.)

Her hand reaches under the blanket, sliding up along the outside of his knee—across the muscles of his thigh—

Louis leans into it, then back into another kiss. “Eggs,” he mumbles.

“Sex,” she counters.

“Well argued, counselor.”

She starts to stand, melting into him. And then she does the porniest thing she can possibly do, which is split her perception for just a moment—now she’s in the owl, looking out through Bird of Doom’s eyes at her and Louis doing the lust-lizard tango out here in the snow.

But a sound snaps her back to her mind and flash-freezes her blood—

The sound of an engine. A car or truck. She stiffens, pulling away—

Louis puts a gentle, reassuring hand on her shoulder. “Probably just Gordy.” From out back of the cabin, though, they can’t see. Miriam hustles toward the corner of the cabin and peers out.

It’s a truck. A rat-trap Chevy Silverado, mint-green. Poking its way down the gravel drive, through the three or four inches of snow that have gathered.

“It is Gordy,” she says, letting out a whistle-breath of relief. Then she sneers. “More like Gordus Interruptus, am I right?”

“We can finish this when he’s gone.”

“Fine.” She sighs.

“I wonder what he’s brought us.”

“I wonder indeed.”

THIRTY-THREE

WHAT GORDY BRINGS

This is Gordy: he’s in his midsixties, head like a pumpkin sitting around too long after Halloween. It gives him a funny underbite and pinched eyes and a nose that kind of lies out across his upper lip like a hot dog left on the side of a car. He is not an attractive man—though, according to Louis, Gordy still gets a lot of tail. Women young and old. Unconfirmed how much of that tail is actually from prostitutes he picks up in Scranton. Miriam won’t judge. Sex work is work, same as bagging groceries and building bridges. A service to mankind, she figures.

Gordy steps out of his minty truck, a brown paper grocery sack in each hand. Louis hurries inside to get on some pants, and Miriam meets the old trucker and helps him with the bags.

“Bit of the ol’ white stuff, eh,” Gordy says.

Miriam shrugs. “Looks like the season came early. I always heard winter had a problem with premature ejaculation.” Then she winks.

Good news is, Gordy’s an old pervert. Not real witty, but he appreciates her wit, and that’s all that matt

ers. He bellows with laughter so hard, the laughter resolves into coughing and wheezing. They step inside the cabin and he’s still laugh-coughing as he sets the bag down. Gordy wipes his eyes and says, “Oh, oh, that’s a good one. Snow’s white. Like a man’s goo.”

“That it is,” Miriam says, suddenly finding the joke distasteful now that someone explained it. Especially using the word goo.

She starts pulling the groceries out—staples, mostly, bread and eggs and milk—and putting them away as if she were a proper domestic goddess. Gordy says he has a few more things, then heads back out to the truck. Louis shows up, pulling a shirt down over his chest. “He gone already?”

“Getting a few more things.”

Louis passes by her to help put stuff away. His hand graces the middle of her back, fingers trailing. A chill grapples its way up her spine, like an electric spark gone up a copper wire. It thrills her. Though in the wake of that touch, she has this feeling like an icicle stabbed clean through her middle. This can’t last forever, Miriam. You’re on the clock. Tick-tock, tick-tock.

That thought: is it her own?

Or is it the Trespasser?

She hasn’t seen her demon once since they’ve come here, which suddenly worries her more than if she hadn’t seen that monster at all. The specter’s absence is more conspicuous than his presence. What is the Trespasser planning? Surely, that demon has not left her to her peace. . . .

Gordy’s back in the door now, and he’s throwing down a couple newspapers. “Got the usual run. Times-Tribune, Morning Call, the Intell.” Miriam doesn’t want to pick any of them up except to throw them in the pellet stove in the other room. And yet, obligation compels her to disrupt her safe little bubble. Soon as she picks one up, she feels her blood pressure tighten as if there’s a pair of pinching fingers closing off the arteries on both sides of her neck.

Thus begins the routine. Miriam sits down at their little nook table, the one that wobbles because two legs are too short (or two are too long), and she begins flipping through the papers page by page, mostly looking at the crime beat.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

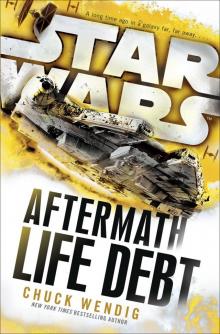

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt