- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Vultures Page 11

Vultures Read online

Page 11

The pressure builds so fast and so furious, it’s like her breastbone is suddenly being stepped on by a brontosaurus. The anxiety of it feels like the air is being crushed out of her, like her heart will soon be pulped like a tomato. Vertigo makes her head spin even though she’s standing still.

Get it together, Miriam.

You have work to do.

Internally, she summons strength and gathers to her all the broken parts of her mind the way one might collect a pack of biting rats in a bucket. It works. She can breathe again. She can stand again.

She walks forward to the guard booth.

“Hi,” she says to the bald man with neck fat behind the gate. “My name is Miriam Black, I’m here to see superstar FBI Agent David Guerrero. I’m here to—” Say the word, say the word, no matter how horrible it sounds, say the goddamn word. “Work.”

The guard mumbles and flips through a list on a clipboard.

“I’m not seeing you here.”

“And yet here I am.”

“Hold on.”

He grabs another clipboard.

“Right,” he says finally. “You’re not in this building.”

“I was directed to this address, dude.”

“You’re across the street.” With a hot-dog finger he flags her past this building. “Go that way. Cross Veteran Ave. You’ll see a little trailer in the lot under the 405 overpass. That’s where you go.”

“A trailer. In a parking lot. Under an underpass.”

“You got it.”

“Really rolling out the red carpet for me.”

He stares at her, saying nothing.

“Okay,” she says. “Good talk.”

Then she proceeds to do as commanded: she heads down the sidewalk before crossing the busy Veteran Avenue and stepping into the cracked, fractured lot. The shadow of the highway above darkens the ground ahead of her, blotting out the sun. A hundred feet away, a portable work trailer sits, gray as a winter day, nestled amongst the cracked and fractured lot.

Miriam steps to the door, gives it a shave-and-a-haircut knock.

A tall woman in a gray suit answers. She looks past a set of rich, dark curls, down a hawk’s-beak nose. “Miriam?” she asks, businesslike.

“The one and only.”

“Come on in. David’s inside.” She steps out of the way, and as Miriam sidles past, the woman says, “I’m Julie Anaya.”

“Nice to meet you, I guess,” Miriam says, feeling suddenly awkward, like she’s the New Kid in Class who has to walk to a far desk across the room as all eyes stare at her. That, even though the trailer is only home to three people, including herself. But the feeling of being an impostor, of starting a new job and not knowing anything about anything, rings clear in her head like a broken bell. Clonnnng. Inside, David Guerrero stands over a folding table, papers spread out before him.

“Miriam,” he says. “Glad you could make it.”

“Kinda have no choice.”

“You always have a choice. This isn’t prison.”

“But prison is prison, and this gets me out of that.”

He shrugs. “Fair point. Like our office?”

She takes it in. All 300 square feet of it. The three desks, the file cabinets, the little air conditioner in the window, chugging away. “It’s about as inspiring as a telemarketer’s cubicle.”

“It’s not flashy,” Julie says. “But it’s the job.”

Miriam eyes her up. “Are you . . . ” To David she reiterates the question. “Is she . . .”

“A psychic?” he asks.

“No,” Julie answers.

“Are you a believer in all this psychic stuff?” Miriam asks.

“I am a believer in results.”

“You want coffee?” David asks, pointing to a glass carafe next to a little swan-neck water kettle. A kettle that appears to be electric, since it’s plugged into the wall. “It’s pour-over.”

“I don’t know what that means, but sure, long as it’s black as the Devil’s asshole.” At that, neither startle, nor do they give her alarmed looks, so she either figures she’s dealing with a couple A-grade professionals or the two of them have gone suddenly deaf. Usually, shocking people is easy—you curse a little, start talking about sex and death and buttholes, everybody gets their tender nipples in a quick pinch. But these two are un-flummoxed.

David then performs what could only be described as a meditative act. Hand-grinding beans. Pouring those ground beans into a metal filter. Boiling water and then gently pouring the water atop the grounds in an easy, languid spiral. Steam rises like a couple of coffee phantoms, and with them come a coffee smell like Miriam has never before taken in. She nearly passes out.

He hands her the cup.

She takes a taste.

“It tastes like coffee smells,” she says.

“I make a good cup,” Guerrero says.

“I want to fuck this coffee.”

“You should probably let it cool down first.”

“Fair point.”

“Shall we get to work?”

Miriam takes another long, noisy sip of the black brew, savoring it with her eyes closed. When she opens them again, she asks:

“Where do we begin?”

THIRTY

WE BEGIN WITH THE STARFUCKER

They sit around the small folding table, and Guerrero shuffles the papers present into a neat pile in front of him.

Julie hands him a folder.

From it he pulls three crime scene photos, and slides them across the table toward Miriam.

Were she a different person, these photos might make her blanch. Upon seeing them, she would tremble and clench up to stem the tide of nausea; worse, she would likely fail at that, and thus, she’d probably puke like a sorority girl after too much jungle juice or hunch punch.

But she is Miriam Black. She’s seen a thing or two. She has the emotional constitution and the iron stomach of an autopsy-room technician. The kind who can eat a sandwich over a corpse’s open chest cavity. The kind who might say, Sorry, I dropped a little mayo inside the rib cage, hold on, let me get that, before dipping a gloved finger into the mayo-plop and then popping it back into her mouth.

Miriam Black has seen a knife through an eye, a face cross-stitched with scars, a man lose his foot to a hacksaw in the back of an SUV.

She has herself eaten a fresh human heart.

Even still, these photos are something to see.

In each, a dead body. A dude. Young, but not a kid—mid-twenties, early thirties. Two white guys, one black guy, all of them on a floor, a white sheet covering all but their faces. Or, rather, their total lack of faces.

Someone has taken their faces.

Their skulls have been skinned. The muscles gleam, wet and red. Teeth are exposed like polished marble fixtures. The contours of the skull are there, present without the covering of the face to remind everyone that humans are, in fact, just skeletons lined with layers of meat and leather. The eyeballs of the victims stare up in dead panic, as if witnessing the most horrific thing they can possibly imagine—that, of course, because the face has no skin and the eyes have no lids, and so those big bold peepers cannot be given any mood other than pants-shitting fear. Still, they probably did witness something pretty terrible, which is to say, someone cutting off their faces. And with that thought, Guerrero slides across three more pictures.

Their missing faces have been found.

“The faces were next to the bodies,” Guerrero says, “displayed there, pinned carefully to the wall or near them. As if to make them see.”

In the photos, the faces are less faces and more masks, appearing so precisely because they are eyeless. Eyes, she thinks, really are the windows of the soul. The spark of life lurks there, and without it, the skinned faces look more like gory props than anything else. Their margins sit crusted with the puckered ridgeline of black scab. But the removal of the faces, while crude and hardly surgical, was still performed with a steady hand. The

edges aren’t jagged. The cuts are clean enough. There aren’t many mistakes.

“This isn’t what killed them,” Miriam says, sipping coffee.

Guerrero nods. Another three photos.

In these, the plastic sheets have been peeled back to show that they have been unzipped like a backpack, their guts bulging and spilling out.

“He guts them after,” Guerrero says. “Though that may not be what kills them either. We found in their bloodstream the presence of a drug: succinylcholine chloride, brand name, Anectine. A paralytic—neuromuscular inhibitor. The injection site is in the side of the neck. We aren’t yet clear if the drug is meant to paralyze them so that the Starfucker can do his work without much interruption, or if it is the thing that ultimately kills them—”

“Or both,” Julie says, chiming in.

“I’m sorry, did you say Starfucker?”

Guerrero nods. “The serial killer has been given that nickname.”

“He gave it to himself?”

“Why do you assume it’s a man?” Julie asks.

“Aren’t most serial killers men? White dudes, actually?”

Julie stiffens. “Not necessarily. Women commit ten percent of all homicides, but 17 percent of all serial murders. Which means they’re likelier to be serial killers than killers of opportunity or passion.” The way she’s looking at Miriam, suddenly Miriam gets the sense there’s some other nasty business going on here: Julie, who seemed cold and businesslike at the outset, has the vicious stare of a praying mantis, and she’s pointed that predatory gaze right at Miriam. The gaze of a hunter fixing intent upon its prey.

“You’re accusing me of being a serial killer,” Miriam says.

“Not accusing. But I am suggesting you might be deflecting. Or projecting. Perhaps women are more often serial killers—they’re just too smart, too capable, to get caught.”

“Or maybe,” Miriam seethes, “men swim in a septic pool of bad ideas about tough guys and big dicks, and they float there, soaking in it, gulping down mouthfuls of that shit, and it gets inside them, infects them, makes their blood go black and sour. Fathers take their sons and shove their heads down under the water, too, just to make sure they all get a taste. Maybe men are fucking broken. You ever think that?”

“You say fathers but classically, it’s not their fathers, is it? It’s their mothers. Missing fathers and bad mothers.” Julie’s gaze narrows down to a laser focus: eyes like a pair of nail guns trying to stick Miriam to the wall. “Know anybody who fits that description? A bad mother? A missing father?”

“I don’t like where this is going. And you’re a sexist twat.”

Wham.

Guerrero slams the flat of his hand down upon the table.

“We are not here to discuss toxic masculinity, nor are we discussing whether or not Miriam Black is a serial killer. That is not our purview today. Our purview is catching a real serial killer who, yes, has been called the Starfucker, and he has been called such because he preys upon young up-and-coming actors in Hollywood. We did not give him this nickname, but rather, a producer did: Jack Ellison. He said, and I quote, Probably some aggrieved starfucker did this; Hollywood’s thick with failed actors and spurned fans.” Guerrero reads from a page in front of him when he says that quote. “Around the Bureau, the name stuck. I wish it hadn’t, but every serial killer is in want of a catchy name, so here we are.”

Miriam keeps her stink-eye pointed right toward Julie even as she responds to Guerrero: “Is the news having a field day over this?”

“So far, the news hasn’t found out. But they will. They always do.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“Three months. One victim per month. Always on the same day: the eleventh. And January eleventh is in three days.”

“So, we’ve got three days to catch the Starfucker.”

He nods. “Or he kills again. Potentially.”

“That certainly sounds like a Miriam Black situation,” she says.

“Yes, which means we need to get to work.”

She holds up a finger. “Before we do, I want to know some things.”

Julie crosses her arms in defiance, but Guerrero shrugs. “Go ahead.”

“Three things, actually.” With each item, she holds up a finger, one two three. “First, I want the name of the psychic who you said could help me. Someone who can help me contact a . . . spirit. You said you knew someone, a medium; I want to know who that is and how I contact them. Second, I want to know who you are. You, David Guerrero, have a psychic power too, and I want to know what it is. Third and final? I want to shake her hand.” Miriam points all three fingers at Julie. “I want to see how you die, Agent Julie.”

Guerrero leans across the table.

In a quiet voice, he says, “No, no, and no.”

Miriam laughs.

“You’re fucking with me.”

“I am not fucking with you, Miriam.”

“You need me. I want these things.”

“You’ve made your demands, and we’ve given them. Money, healthcare, an apartment. You’ll also be free from any charges related to the many deaths that have been left in your wake, including a one-time FBI agent, not to mention your ex-lover and his fiancée.”

She snarls, “Then I walk.”

“So walk. Your apartment is paid up till the end of the month, though it won’t matter. We’ll have you and your girlfriend in custody by nightfall.”

“Fuck you.”

“Think carefully, Miriam.”

“Eat shit carefully, Guerrero.” She stands up, knocking her knee in the table on purpose—it rattles and lifts, sending papers sliding to the floor. As Julie struggles to catch them and pick them up, Miriam heads for the door, kicks it open, and escapes this shitty job.

THIRTY-ONE

THE GREAT EGRESS

Outside, though she stands in shadow, the sun in the distance thumbs her square in the eye, and she winces against its hot, spearing light. She wishes she had a pair of sunglasses in her panties the way Tighty-Whitey Steve did. But she doesn’t, and so she steps down from the FBI trailer with her arm up over her eyes to shield them.

Shortest time on a job ever, she thinks with pride so smug, it might as well be vegan.

A sense of freedom blooms inside her. It’s like watching a rocket go up, up, up, punching through a layer of clouds toward the blissful void of space beyond, a glittering eternity of stars:

I can go anywhere.

I can do anything.

I am not bound by—

And the rocket sputters. It tilts and spirals. It drops back down through the cloud layer like a brick. Because the reality again hits her that she has to be responsible. She’s routinely run reckless and roughshod through everyone else’s existence, doing whatever feels best and most fuck-you-ish at that particular moment in time. Now, though, Gabby’s life is once again in her hands. The baby’s life is in her hands. Louis’s legacy is with her, too. And, selfishly, so too is her ability to escape this curse and to maybe, just maybe, be a better person. A different person.

But she only gets that if she plays ball.

And what if this is what the Trespasser wants? Her working with Guerrero and the FBI? Is she doing the demon’s bidding even now?

“Fuck!” she yells out loud.

It startles a crow, who had been poking at a Carl’s, Jr. fast food bag. The bird takes flight, squawking angrily. Miriam can feel, for a moment, its irritation at her. Crows, she knows, are smarter than people think. They can remember things about you. They can remember your face. That crow will remember her face as the shitty bitch who startled it.

Behind her, the door to the office opens.

Julie Anaya steps out.

“We will concede on one of your points.”

Miriam gives her a look.

“You can see how I die,” Julie says.

“Really?”

“Really.”

“That’s something, at leas

t.”

“Will you come back inside?”

“I want to do it now. You. Your death.”

Julie pauses. “How does it work again?”

“You know.”

And she does know. Because Julie puts out her hand.

And Miriam takes it.

INTERLUDE

HOW JULIE DIES

Julie Anaya looks upon herself in the mirror of the makeup table at which she currently sits. She marvels darkly at how she looks: whittled-down, carved away. It’s not her age: at sixty, time has taken its expected toll, leaving behind the furrows and divots, the dings and dents, the liver spots and the amplified imperfections. It’s the cancer. Breast cancer has taken parts of her away, piece by piece. One breast, then the other. Then her hair, twice—this time, it’s started to grow back again, her scalp a peak of salt-and-pepper stubble. The radiation stent in her too has left its mark. And the cancer has done its deeper work, too: her bones ache, she can’t sleep well, she feels tired all the time. This has been a ten-year journey for her.

And it ends here today.

On the makeup table sits a gun.

She just received a call an hour before where Dr. Tranh told her that the cancer was not only back, but it had metastasized. It was all throughout her now, insidious, like the roots of an invasive weed. He said they would need to operate on her abdomen, because she had a tumor in her pelvis, and also they’d need to do the standard run of chemo and radiation and—

And it was too much. She didn’t tell Tranh that. She made the proper mouth noises, mm-hmm, yes, yes, we can fight this, mm-hmm.

But she didn’t mean them.

She can’t fight it.

They often say that cancer is a battle, and that is true, she supposes: though the truth of it is more complicated than she understood at first. Once, she believed in that battle she was one of the fighters: as if she and cancer were neatly matched up in gladiatorial combat, and whoever had the most diligence and vigor would win. She merely had to outlast the disease.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

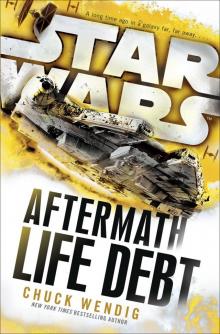

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt