- Home

- Chuck Wendig

The Raptor & the Wren Page 11

The Raptor & the Wren Read online

Page 11

Down the hall. To the end of the hall. To her mother’s old room. She’s not going to stay downstairs. Not tonight. Tonight, she wants a proper bed, damnit.

Her hand falls to the doorknob, a brass Victorian affair with a square-petaled flower on it.

But as the door drifts open into darkness, the smell hits her.

It is a smell with which Miriam is woefully, intimately acquainted. There, on the air, is the coppery spice of blood. And with it, an odorous sublayer of human leavings: shit, piss, sweat. Then comes the sound—

The binaural buzz of fly wings.

Miriam paws at the light switch.

Light bathes her mother’s bedroom.

But blood has bathed the room first.

Grosky’s body is splayed across the top of the comforter, arms out in cruciform, one leg tucked awkwardly under the bulk of the body. Blood spatters the pale walls, specks the ceiling, and is lost against the dark cherry wood of the nightstand and the bedposts. The pillows have been plumped up and set to the side, and sitting atop them is his head.

His head is not attached to his body.

His mouth is wrenched open in a silent, permanent howl. The eyes are already disappearing beneath eyelids so swollen they look like puffy-lipped mouths. A pair of flies lands on his forehead and dances across his dead skin.

(Don’t tell anybody, Grosky, but I think you’re all right.)

The fatigue is gone from her, sandblasted away in a scouring, abrading wave. It reduces her down to powder. She wants to collapse here into fragments, like dust escaping through the gaps in the floorboards.

Questions chase questions. Who did this? Why? Could it have been Wren? Did I judge her poorly? What monster is she?

Is this just a dream? She tries to say the words Stop fucking with me, hoping the Trespasser will hear her and end this display, but the words come out as a popping, incomprehensible whisper.

Behind her, the wood groans under the weight of a footstep.

Miriam slowly turns to meet whoever it is.

No.

“You’re dead,” she says.

(You’re dead, Wren says.)

“And yet here I stand,” says Harriet Adams.

Harriet Adams: one of the two murderous goons that worked for Ingersoll, the Eurotrash drug baron meant to kill Louis until Miriam shot him. Harriet Adams, who thought she was so smart, who believed herself such a master of cruelty that she left a gun in Miriam’s hand in the unshakable belief Miriam would use it to end her own life instead of firing through the door and putting a bullet in Harriet’s ear. Harriet, whose brains got scrambled by a lead bumblebee ricocheting around the inside of her skull, and so the last thing she muttered was the nonsense phrase carpet noodle. She is dead. Miriam killed her. Miriam stood over her body as her blood and brains leaked out of her ears and onto the floor of that Pine Barrens house.

And yet here I stand.

She is a brutish plug of a woman. Dark hair like a helmet, chopped at hard knife-slash angles. Face so pale, it’s the porcelain of an urn meant for human remains. Harriet stands stuffed in a pair of dark dungarees and a maroon sweater, wearing a dead look on her face: implacable and distant.

In her hand is a machete.

Its blade is thick with congealing blood.

Miriam trembles, feeling suddenly cold.

“You’re not real,” Miriam says.

“I am as real as anything you’ve faced.”

Her voice shakes when she says, “I shot you. In the head.”

Harriet tilts her head sideways—showing that her left ear is a ruined, crumpled mess, like a rotten Brussels sprout mashed against the side of her skull. “I remember.” She shrugs. “I earned it. I don’t blame you. I was overconfident, and that blinded me to what was to come.”

A clot of blood slides off the machete and plops against the floor.

Miriam realizes: Harriet is blocking her way to the stairs. If she’s even real. She’s still waiting for Harriet’s face to shift, for her skull to split like an axe-cloven pumpkin and for the Trespasser to emerge, singing and dancing: Hello my honey, hello my baby, hello my ragtime gal.

“I’ve been looking for you,” Harriet says. “And now I found you.”

Fuck this. Miriam runs.

She knows better than to go through the dead woman with the machete, so she goes the other way instead—her toes plant and she twists around, bolting back through the doorway and into her mother’s bedroom, where Grosky’s body and head wait separately on the bed like jilted lovers. As she powers through the open space, she palms the door and slams it hard behind her, wham.

The bedroom has no other door.

But there’s a window. And beyond it, a roof.

She sprints across the room—

It happens so fast, it takes her a few seconds after she faceplants onto the floorboards to figure out what happened. I slipped, she thinks. In the blood.

The door to the bedroom flies open, bashing against the wall. Harriet Adams, unliving monster, stalks forward as Miriam scrabbles to her feet. She’s slow, too slow, and she realizes much too late that if she wants to survive, she’s going to have to fight.

Miriam stabs out with a foot, catching Harriet in her chest. It’s like kicking a tree stump. The woman barely budges—she doesn’t even make a sound. All she does is raise the machete, and Miriam sees a glimpse of the future where the blade cuts down clean through her leg, her foot flopping onto the floor like a fish off a line, and suddenly her mind goes to Ashley Gaynes. Ashley, one foot gone after Harriet cut it off in a speeding SUV. Ashley, eaten on a boat by greedy gannets. Ashley, one more monster in Miriam’s life who came to hunt her.

(Miriam Black: fate-taker, river-breaker, monster-maker.)

Harriet brings the machete down, slicing through open air. Swish. Miriam’s already somersaulting backward—a clumsy maneuver that has her slamming back into her mother’s old walnut dresser. The mirror atop it rattles and bangs. Miriam uses the dresser to get to her feet—

Harriet lurches in, swinging—

Miriam cries out, pressing herself against the corner as the machete blade drops hard against the top of the dresser. It thunks into the wood.

And there it remains, stuck.

Harriet growls like a trapped animal as she gives the blade three futile tugs. Miriam doesn’t waste the opportunity. She kicks out hard against the side of Harriet’s knee. The leg bends inward, in a way legs are not supposed to bend. Something snaps as the limb kinks.

Bitch, I’ll break you into sticks, Miriam thinks. For Grosky.

But the other woman seems to register no pain at all even as her hip dips from her injured leg. And the hard motion is enough to jar the machete free.

Harriet clubs Miriam in the face with the back of her fist. A white nuclear flash goes off behind Miriam’s eyes. Her legs carry her backward as her hands instinctively fly up. The machete blade grazes the side of her left forearm, peeling off a flap of skin and sending up a spray of blood. Miriam, half-blind and dazed, throws a punch. It whiffs through open air.

One of Harriet’s stubby hands grabs the back of Miriam’s neck like she’s a whelped, whooped puppy—

Next thing she knows, she’s flung forward into one of the bedposts. Her shoulder cracks hard against it. Her foot hits the slick of blood and slips out from underneath her. She goes down. Ears ringing like sirens. Everything pounding like war drums. Even as she grabs the bed and tries to pull herself up, a boot presses against her back, pushing her to the floor.

Harriet clambers atop her, mouth up against Miriam’s ear.

This is what Harriet tells her.

INTERLUDE

HARRIET’S STORY

I have been looking for you for a very long time, Miriam.

Hold still. No, no, don’t struggle. I want you to know this. I want you to know my torment. I want you to be aware of what I went through to be here with you, right now, my knee in your back, a machete against your throat.

> Once, I thought myself the paragon of the natural world. Mankind, as I saw it, had gotten too far away from its animal nature. Do you know why we have canine teeth? Because we are predators, Miriam. Hunters red in tooth and nail. We are driven by our genes to hunt and to conquer, to kill and to eat what we kill. Our genes are expressed in our ideas—memetics to mirror our genetics. But we have convinced ourselves that our ideas are of a higher mind. That we are somehow better than our crass, predatory nature. And yet, our ideas drive us to be more like the predators we hope we are not. This cognitive dissonance weakens us, I once believed. We struggled against our nature in the way of one struggling against the sucking force of quicksand. The more we fight, the deeper we sink.

I thought I had it all figured out.

I thought I was better than you. I truly did. I found that diary of yours. Your countdown to suicide. I saw a way to prove that I was the alpha and you were the omega. I would not have to kill you—I would let you kill yourself.

And then you shot me.

You put a bullet through a door and into my head.

You proved me wrong. I died there on the floor.

Or so I thought.

From darkness, light bloomed behind my eyes. Something pushed and pulled at my wound, like a finger probing. A shadow came to me. A shadow shaped like Ingersoll, long and lean, lithe and hairless. It slid atop me. It filled me up through that hole in my head. Breath plumped my lungs once more. And again my heart began to beat.

I sat up.

My mouth tasted like pennies and rot.

By the time I walked back to the world, I found that I had been gone from it for six months. My body never decayed. Nobody ever found me there in the Pine Barrens. I lay there for those months, beetles colonizing my bowels, worms filling my spaces. I had to vomit them up. I had to defecate them out. I spent days purging what was in me: emptying what had laid claim to my void.

By the time I came back, the world had moved on without me. Frankie was alive and had found new work. Ingersoll was dead—another casualty of you.

My memory was alive and well. I did not forget.

And in me now was something new: that shadow. A second being inside me. It’s what I imagine it’s like to be with child. I feel it in my spaces. A parasite, but a beneficent one. I give to it. And it gives me life.

It told me to bide my time and I did. I returned to what I knew to do: I went back and slowly, surely began rebuilding Ingersoll’s empire. I reconstructed relationships. I resurrected supply lines. Just as I had been reborn, so too would the work. I never forgot you, though. I lost you, yes, but I knew one day I would find you. I knew we would meet again and I would kill you. The shadow assured me that this was my intersection. That it was my destiny.

That is a thing I believe in that I did not before. Destiny. I should have seen it all along. I hadn’t really been listening to Ingersoll. He believed in a greater, stranger universe: a universe of fate and mystery, where one could portend the future and direct the outcome by rolling knucklebones or by sorting through a pile of hot entrails. I believed in nature over everything.

But I believe in something else now:

Supernature.

That is why you defeated me the first time. I was nature. You were supernature. You had power. You had a gift. Ingersoll knew this but I was blind to that. Now his shadow has filled me, and now I have power too.

I looked for you for a long time. I almost found you. When a competitor of mine—the Haitian, Tap-Tap—found himself unseated from his throne, it did not take long to discover that Miriam Black had been present, once more toying with fate and, in this case, changing my world for the better. Tap-Tap’s end helped my business flourish. More recently, in Tucson, the cartels reported that someone had intervened—they had planned to kill a man named Ethan Key, but they found that someone had already done that job for them.

And again, my job got easier.

I should thank you, I suppose. You made me who I am now.

Thank you. Thank you for teaching me how weak I was. Thank you for aiding my work. I mean it. Thank you. But make no mistake: my gratitude does not come part and parcel with forgiveness. Our nature is not to forgive, is it? You do not forgive. You act. You change fate. You move the world, one degree at a time. One life saved, another taken. Forgiveness is passive—it is taking your hands off the wheel and letting go. But you never take your hands off the wheel.

And that’s how I found you. Because here you are, doing what you do. Meddling in my business once more. You left a string of bodies across this state, and the latest was one of mine. Donald Tuggins. He is dead by your hand, and so I am conjured. I am conjured and fate has pushed me to you. This time, fate worked in the hands of one of your own:

Your uncle, Jack.

He was very glad to tell me where I could find you, Miriam.

And so here I am. And here you are. It is time to end our dance.

Here is what’s going to happen:

I’m going to cut off your head.

And then I’m going to take our your heart.

Your head I will leave behind to watch as I eat your heart. That is how I take your power. That is how I conquer.

TWENTY-EIGHT

DEUTERONOMY 19:21

As Harriet goes on and on, mashing Miriam’s face to the floor, it comes up out of her like the howling wind of a coming hurricane: one moment, Harriet is ending her tale with That is how I conquer, and in the next, Miriam’s chest is tightening and a white giddy bloom is filling her mind. She laughs. No, she guffaws, breathless and constant and without restraint. Her eyes are wet with tears. The blood is sticky underneath her forehead. Miriam laughs and laughs and laughs, braying like a happy cow in defiance of the slaughter to come.

“Shut up,” Harriet seethes, tightening the blade underneath Miriam’s throat. But Miriam can’t stop. She keeps on cackling, even as the blade nicks the skin around her neck, her blood joining with that of Grosky’s.

“Can’t . . . ,” Miriam gasps. “Can’t stop. Too funny.”

“Why? Why are you laughing?” Harriet demands.

“Laughing because . . .” Miriam swallows hard, and the knot in her throat has to pass the cold steel of the machete pressed there. “Because for being so smart, you’re such a dumb, dumb cunt.”

“What?”

“You’ve been looking for me all this time and—” Miriam laughs harder. “I haven’t been hiding! My name is on police reports. I own two houses. You could’ve just Googled me, you stupid fucking bitch.” She laughs so hard she’s crying now, barely gulping air.

“Shut up,” Harriet says. But when Miriam won’t quit, she bellows it: “Shut. Up!” She pounds her fist against the baseboard of the bed, wham.

Across the room, a new sound—

A thump.

It’s enough to distract her. Harriet lifts her head over the bed to look in that direction, toward the window—

Miriam grabs the bedpost and pulls, dragging herself out from beneath Harriet and under her mother’s old bed. Into cobwebs and lint, into dust bunnies stuck to the floor in coagulating blood. Harriet grabs at her ankle, but Miriam twists and wrenches away, sliding completely under the bed. Thus begins a game that would be cartoonish were it not for the stakes—Miriam slides to one side of the bed, and when Harriet goes to that side to reach under, Miriam slides to the other side. Back and forth, back and forth, careful to keep all her parts away from Harriet’s grabbing hand and slicing machete. (Keep all limbs inside the vehicle at all times.) Finally, Harriet has had enough.

She picks a side and begins to crawl under, pawing and slashing.

Miriam goes out the other side—

And as she draws herself up and back toward her mother’s walnut dresser, she sees what caused the distracting thump in the first place:

Grosky’s head. It fell off the pillow when Harriet hit the baseboard.

Here she comes.

The venomous bulldog woman is back up over the fa

r side of the bed, crawling across it with her normally dead-eyed face alive with hate. She’s like a rabid animal, driven by the singular urge to kill, kill, kill.

I need a weapon. I need something—

And then she has it. Miriam reaches down, grabs a hank of Grosky’s hair, and just as the woman gets close, she smashes the dead man’s severed head into the side of Harriet’s face. The woman grunts, rolling off the end of the bed and hitting the floor so hard, the whole room judders. Miriam whispers a hasty apology to the head, then flings it in that direction—it bounces off the wall, knocking a painting of Jesus off its anchor. Both the head and the painting land on Harriet as she struggles to stand. Glass shatters. Harriet rages.

Time bleeds like arterial spray. Miriam cannot waste any of it. She pushes herself up against the window, continuing her original plan—two flips of her thumb disengage the lock, and she gets under the window and forces it open. A blast of October air hits her in the face and robs her breath. She reaches out, grabs the outer ledge of the exterior window, and hauls herself out.

Hands grab her ankles. Firm, crushing hands. Gone is the machete—Harriet must have dropped it. The tendons and muscles in Miriam’s arms burn as she struggles to keep pulling herself out. She thrashes about, kicking her legs. She looks back over her shoulder, sees Harriet’s eyes are bright and cruel as knives, and the grin on her face is a maniac’s half-moon smile. As if to confirm, she opens that maw of hers wide, wider—

She bites down on Miriam’s calf. Teeth sink into muscle. Miriam screams. Blood bubbles around Harriet’s lips and across her pale, puffed-up cheeks.

The air stirs with movement. The wind is suddenly fierce, riffling through Miriam’s hair like a pair of fingers. And with that, a shape swoops in past her, a shadow pulling away from the night.

The great horned owl dives silently though the window, claws up and out, pointed right at Harriet’s face. The woman has no time to react. The bird’s talons go right for her eyes, and suddenly, the teeth embedded in Miriam’s calf are gone as Harriet juggles her own feet backward, an owl attached to her face.

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

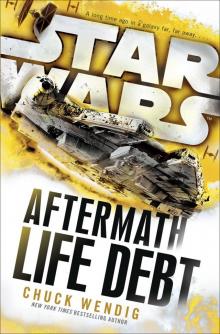

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt