- Home

- Chuck Wendig

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Page 12

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Read online

Page 12

“As a candidate, he has access to them. They protect him.”

This Orishen—Sinjir would very much like to pay him a visit. He would then like a heavy stick to pay a visit to the man’s knees.

“Be assured,” Sinjir says, “Conder will find something.”

Minutes later, the slicer emerges.

“I didn’t find anything.”

Well, thanks for that, Sinjir thinks. “How? How is that possible?”

“How? There’s nothing to find. No listening devices. No cams. Unless Wartol has someone building devices who’s more sophisticated than I am.” The slicer smirks. “And no one is more sophisticated than I am.”

That damn smirk. That big-eyed confidence. Those cherub cheeks puffing out underneath his scratchy beard. You adorable, incorrigible demon.

Still. Can’t let Conder have his day. “You failed us. Someone out there is more sophisticated, it seems, because—” Because it’s easier to insult your abilities than admit I’m wrong. “Because I’m right. Plain and simple.”

“I’m sorry, Sin, but I mean it—I didn’t find a damn—”

The small probe droid, held fast in Conder’s hand, begins to beep in fast staccato. It shudders in his grip. The slicer utters a grunt of surprise as the droid suddenly leaps out of his hand and takes flight.

It doesn’t go far, though. It whirls around in a circle and stops in front of the protocol droid’s gleaming face.

“Oh, my,” T-2LC says, alarmed.

The probe scans the protocol droid’s face—

And then it lights up like a detonator about to pop. Flashing lights! Klaxons! A vibrating buzz! Conder swipes it out of the air and powers it down, clipping it to his belt as it falls silent.

All eyes turn toward the protocol droid.

“It’s not me, mum!” the droid objects.

Han Solo scowls and reaches for the protocol droid. “Elsie, you oughta hold still. This is going to sting a little.”

—

Mon Mothma comes into her office. Tired. Feeling gutted. She has just given her speech to the Senate—her last plea, an easy one that asked for their vote to send the brunt of the New Republic’s military to Jakku in order to end the Empire’s oppression once and for all. She was uncharacteristically jingoistic, but they need this vote. The chancellor told the hundreds of senators present in the last Chandrilan session that this will be the defining battle of the war. It is likely to be the final battle of the war. She presented to them all the facts as they had them: data from probe droids and the Oculus that demonstrated plainly that the bulk of Imperial forces are present and accounted for. The numbers, she reminded them, are on their side. They are no ragtag junkyard fleet going up against a monolithic battle station, not this time. Their own military forces have more than tripled since the destruction of the second Death Star at the Sanctuary Moon. Meanwhile, the Empire’s own fleet has been whittled away—

A tree, to a branch, to a bundle of splinters.

And then dust that becomes nothing as the wind takes it away.

Or so she hopes.

We can win this, she told the Senate. She meant it.

Then her time on stage was over. Applause came up behind her like a rising wave, urging her forward out of the Senate house and pushing her all the way back to her office. Now she feels stripped down, hollowed out, weary, bleary, and done.

I can’t be done yet. Soon. But not yet. Yes, the day has nearly eaten her alive. But it did not. She has persevered.

And soon, Mon Mothma shall be triumphant. At every turn, some new snarl presented itself and she (or Auxi, or Ackbar) had to spend additional time unraveling each knot. Never mind the overwhelming number of administrative duties that threatened to draw her down like a slurry of sucking silt-sand. Everything is prepared. The moment the Senate gives their easy approval, the mechanism of war will wind up quickly, triggering events as needed. It calls to mind a match of rivers-and-roads, the old Chandrilan game of toppling over tiles—one falls into another and into the next thereafter, and they speed along. If you place them correctly, they all fall down, and they fall more swiftly than those of your opponent. If you fail…they fall too slowly, or never fall at all.

Once the vote is in, the ships launch.

The ground forces mobilize.

Everything begins.

And hopefully, her tiles fall faster than the Empire’s, and this is truly the end of that oppressive regime’s rivers and roads.

She collapses into her chair.

Auxi sweeps over, a bulbous long-necked bottle of very good brandy held in the same hand with which she precariously grasps two glasses by their rims. “I think this calls for a nip.”

“What’s the old saying? You can never count the stars, for some may already be dark. The vote isn’t in yet, Auxi.”

“But it will be. Momentarily.” She sets the glasses down and begins to pour. Rich amber liquid sloshes around the bell of each. “And we’ll win. But what does it matter? After the day we’ve had, I think we deserve a bit of the good stuff. Oh! And your numbers are already improving nicely. They were up before you even stepped on stage.”

Mon sighs and takes the glass in her good hand. “People do like war.”

“No, shh, stop that. People like to know that they are safe. And in this case, if that safety is earned by grinding the last Imperial stormtrooper into the dirt—then count me among them.”

Their brandy glasses tink as they tap together.

Mon takes a sip. The liquor is warm in her mouth, and as she swallows, it spreads its heat to her throat and her belly. As it goes down, it’s like a zipper opening her up—all this tightly packed material inside her heart suddenly unspooling. She feels like she is almost ready to breathe a sigh of relief and sleep a very long sleep.

Don’t get too comfortable, she cautions herself. You won’t be able to rest long on your laurels. Ackbar will lead this battle, but it is you who oversees the war, Chancellor.

As if on cue, her office door chimes. Ackbar enters.

She is poised to ask him if it is time. Time to launch. Time to complete the dread task they set out to complete many years before with the first stirred embers of the Rebel Alliance. But she sees now the stark look on his face. Mon Cala are hard to read for most humans, but she knows Ackbar well—and she spies the reluctance in his stiff-backed posture, in his curling chin tendrils, in his half-lidded eyes.

“Tell me,” she says.

“The vote did not pass,” he says. “We are grounded, Chancellor. The fleet will not go to Jakku, and there the Empire shall remain.”

Cold, rank water hits Norra in the face. It pours over the top of her head, a sour bile-spit smell filling her nose. She coughs and sputters, standing up inside her cage. Two stormtroopers stand on the grated metal ceiling of the prison in which she sits. Above them, the Imperial fleet hangs, veiled behind bands of gauzy clouds.

One of the troopers holds a bucket. The other has his blaster rifle pointed down. From her vantage point below them, with the sun above, the Imperials look like little more than shadows—scavenger birds ready to pick her bones as soon as her flesh gives up.

“Wake up,” the one with the bucket says. He lets it hang loose, and it knocks against the side of his armor—armor that’s no longer the pristine white of most stormtroopers. This armor has been marked and gouged, painted and carved into. The one with the blaster rifle has blood-red dye spattering the face of his helmet, shaped into the crude icon of a skull—taking what was always metaphorical about the stormtroopers and literalizing it. We are the agents of death, it says. We are killers.

“I could just shoot her,” the rifle-holding trooper says. He gestures down through the bars of the wrought-metal cage, the tip of his rifle poking through. “She’s just another mouth to feed. I could close that mouth. Permanently.”

“Do it,” she whispers.

He does.

No!

The blaster goes off, and everything aroun

d her lights up red—

The bolt digs a furrow out of the hard sand-pack beneath her feet. She dances away from it, panic throttling her.

“She’s awake now,” the bucket-holder says.

The two troopers laugh and keep walking, boots clanging.

Norra kneels down and weeps.

—

Hours later, she’s up and working a kesium gas rig—it’s a big cylinder-bore screwed into the sand, and it needs people all around it to turn valves and tug levers to balance the rush of gas coming up from beneath the mantle. Let too much up at one time and the whole thing pops its top, maybe blowing them all to vapor. Let too little up, and the shaft-line seals shut as the sand collapses back into the channel. She’s here, chained along the edge with half a dozen other prisoners, all shackled around the circumference of the well. If any one of them fails, they either get punished or get dead.

Worse, she still smells like bile and spit. That, courtesy of the bucket dumped over her. It wasn’t water. Oh, no. Nobody would waste water on this planet just to wake up a prisoner. It was backwash from a happabore trough: rancid water sloshed in and out of their leathery maws.

Norra, at this moment, has never felt so alone.

When the troopers brought them here, they scanned and ran their faces, said that there was a bounty out for Jas. Before Norra knew what was happening, they were throwing her friend aboard a sand-scoured shuttle—and just like that Jas was gone.

That was a week ago. Or longer. Norra can’t even tell anymore.

After they took Jas, some pock-cheeked officer asked Norra point-blank if she wanted to die, or if she wanted to work. The answer was easy. If Norra gets dead, then that means Sloane escapes. Death was not an option. Not until revenge had its day.

I’ll work, she told him.

So they brought her here. Where here is, though, she barely knows. Kilometers from someplace called Cratertown, apparently.

And so she works. Every day she works this same black valve, the metal on the wheel so hot it first blistered her fingers—by now, though, those blisters have turned to calluses, and the skin around them is dry and splitting. It doesn’t even bleed. I don’t think I have blood anymore. Just dry Jakku dust whispering through her veins.

To her right, a hollow-eyed alien hunches over a set of levers. The bone-white creature doesn’t talk much. Occasionally it moans into the backs of its hands. It weeps tears that glitter like silica.

To Norra’s left is a dirt-cheeked man, his face round and thick even though the rest of his body looks like a skeleton draped in the rags of his own skin. He sometimes grins over at her—the broken-toothed smile of a bona fide madman—and he sings little songs.

Gomm is his name. Gomm, Gomm, the biddle-bomb, the womble-balm, speaking on the intercom, doozy woozy holocron…His words, not hers. One of his bizarre songs. He reminds her in a way of Mister Bones, if Mister Bones were a lunatic prisoner stuck on a dead dirtworld.

“Fancy a mancy,” he says to her.

“Fancy a mancy,” she answers back, not having any idea what it means. It matters little.

Norra needs to get out of here.

An obvious sentiment, but true just the same. She’s been thinking on escape plans, and none of them are sensible.

The chains that bind them are literally just that: chains threaded through metal manacles. Breaking them doesn’t seem to be an option. Not by herself, at least.

She thought about sabotaging the rig and letting it explode. But what good would that do her? It’s a fantasy to think that somehow it would bulge and detonate in just the right way, shearing her chain and letting her free. Far likelier to turn her into a scattering of charred bone across the sand. Plus, this kesium rig is not the only one. Front to back, another dozen rigs topping another dozen wells sit all around. If this one goes, they all might.

Which means she might not kill just herself.

So that’s not an option. What, then?

She has no answer. She keeps working. She tries to cry but no tears come. Norra has no more tears just as she has no more blood. It seems that on this planet she’ll just dry up and flake away when the night winds come.

—

At the end of the day, they throw her back in the cage. A portion of food lands in with her: a rubbery plastic packet of protein mush. Sometimes it’s a powder, and they give her a little water with it, and the powder sizzles and turns into something: a ballooning piece of bread, a cup of gruel, a biscuit so hard it’s like biting into a fresh-baked brick. Today, though, it’s just this packet of goop. She tears the top off with her teeth and greedily slurps it down. It tastes like the happabore spit smells.

But it will sustain her.

“Ah, nothing better than eating one’s own sick.”

That voice. She knows it.

She wheels around on the one who spoke.

And there stands Sinjir outside her cage. A cocky tilt to his hips and a smug, self-satisfied sneer on his face. He nips from a flask. “Norra, dear.”

“How…?” she asks.

“Who can say? I am called and conjured. I’m here to rescue you. My, my, we do find ourselves in cages, don’t we? And I don’t mean that as a thematic conceit, either, I mean—well. Look around you. Metal cage. Imprisoned once again. Naughty business, this Empire.”

“Well, get me out of here!” she says.

A hand falls on her shoulder. She startles, crying out, raising a fist to whoever would grab her—

“Whoa,” Temmin says, holding up both hands. “Hey, relax. It’s okay. It’s me. It’s your son. We’re getting you out of here. Me and Wedge. Just sit tight.”

Her son. He’s here. He came back for her. And there behind him is Wedge Antilles, and he’s got that boyish smile and those dark, warm eyes, for a moment the pulse in her neck quickens…

And yet how are they here in the cage with her? That doesn’t make any sense at all. Suddenly she’s doubling over, her middle clenching up as waves of heat and cold take turns crashing into her. Sweat slicks her brow even as her lips go dry. She tries to say her son’s name, but all she can manage is a sad mewling, like a rodent caught in the teeth of a trap.

She looks up to him, but he’s gone.

So, too, is Sinjir.

They were never here at all, were they?

No. Just illusions pressed upon her by the heat. Suddenly she understands Gomm—the sun and dust have blasted his sanity away, like a coat of paint scoured free. And she wonders if sanity is really just that—something to be worn off, a veneer that with enough pressure and effort can be stripped away. Civilization, too, can fail the same way, can’t it? Scraped down to nothing, leaving only the raw metal of anarchy and oppression behind. And madness. That is the Empire. That is what it has done to her and to the galaxy. A corrosive force, eating away at everyone and everything.

A new illusion seizes her. This hallucination reaches her ears before her eyes, and she hears the mechanized voice of her son’s droid, Mister Bones. Trails of sand slither along on a sudden wind like snakes, and they carry those familiar words of his, “ROGER-ROGER,” distorted and broken by static. And sure enough, the hallucination completes itself as it reaches her eyes, too. Norra lifts her head (no small effort) and glances over her shoulder to see Bones trotting along through the camp, pushed along by a stormtrooper whose mask shows the carvings of endless jagged spirals.

The trooper says to a nearby officer, “Found this out by the steppe. It was poking around another escape pod.”

“Look at this old thing,” the officer says, sitting under a small tent pitched in the dirt. It’s the same pock-cheeked prig who brought her here. Effney, she thinks his name is. How kind of him to participate in my hallucination, she thinks, and laughs out loud at the absurdity of it. He lifts the saw-toothed beak of the old droid with one hand while using the other to dab his brow with a wet sponge. “This old clanker has seen some modifications since the Clone Wars. Probably belongs to some nomad or spacer.”

/>

“I fitted it with a restraining bolt,” the trooper says. “What do you want me to do with it?”

Effney pulverizes the sponge in his fist, and a stream of water spatters his outstretched tongue. Norra knows the droid is just a vision, but that water isn’t. It’s real. So real she can almost taste it. Water…

The officer, done drinking, wipes his mouth with the back of his hand and answers: “I don’t care one way or the other. Destroy it. Wait. No. Send it on the next transport ship heading back to the Ravager. The Old Man is up there, and I’m sure Borrum would find it a fascinating piece of antiquity—maybe he’ll pull for us to get some more portions down here.”

“Yes, sir.” To the droid, the trooper says: “Move along, B1.”

“ROGER-ROGER.”

Norra pushes her forehead against the scabby metal of her prison. She watches Bones march away, his servos whining, his joints crunching as this world’s grit grinds between them.

This hallucination is quite the persistent one. Unless…

Poking around another escape pod…

What if…? Could it be?

What if Temmin sent Bones? Before the Moth hit hyperspace, what if he ejected the droid? Or himself? The heat once more is pushed away from her, this time not from feverish chills but from the cold realization that this is no phantasm. That mirage is no mirage: It’s Mister Bones. It’s really him.

I fitted it with a restraining bolt…

Send it up on the next transport ship…

No. She needs that droid. Bones can save her.

Norra has no plan. Not that there’s any time for one. Suddenly she calls out: “That’s my droid!”

The trooper halts. So does the officer.

Bones keeps walking, until the trooper grabs him with a rough glove and yanks him back. The officer and the trooper share a look, and with the hook of a finger Effney gestures them forward.

The officer stands in front of her.

“You,” he says. “What did you say?”

“I said that’s my droid.” Her voice is raw, as if her vocal cords have been dragged behind a speeder over volcanic stone. She bares her teeth. “I want him back. Now.”

Vultures

Vultures Mockingbird

Mockingbird Wanderers

Wanderers The Cormorant

The Cormorant Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars)

Empire's End: Aftermath (Star Wars) Double Dead

Double Dead The Blue Blazes

The Blue Blazes 250 Things You Should Know About Writing

250 Things You Should Know About Writing Irregular Creatures

Irregular Creatures The Raptor & the Wren

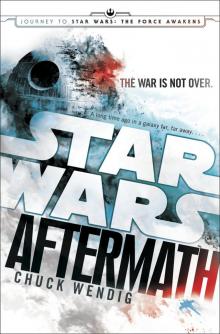

The Raptor & the Wren Aftermath: Star Wars

Aftermath: Star Wars Blackbirds

Blackbirds The Hunt

The Hunt Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead

Tomes of the Dead (Book 1): Double Dead Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits

Gods and Monsters: Unclean Spirits The Harvest

The Harvest Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative

Damn Fine Story: Mastering the Tools of a Powerful Narrative ZerOes

ZerOes Thunderbird

Thunderbird The Hellsblood Bride

The Hellsblood Bride Double Dead: Bad Blood

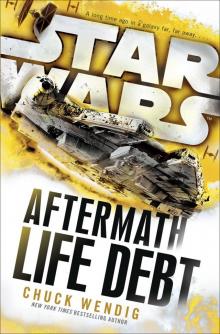

Double Dead: Bad Blood Life Debt

Life Debt